Opinion: The best way to deal with the debt ceiling: Ignore it

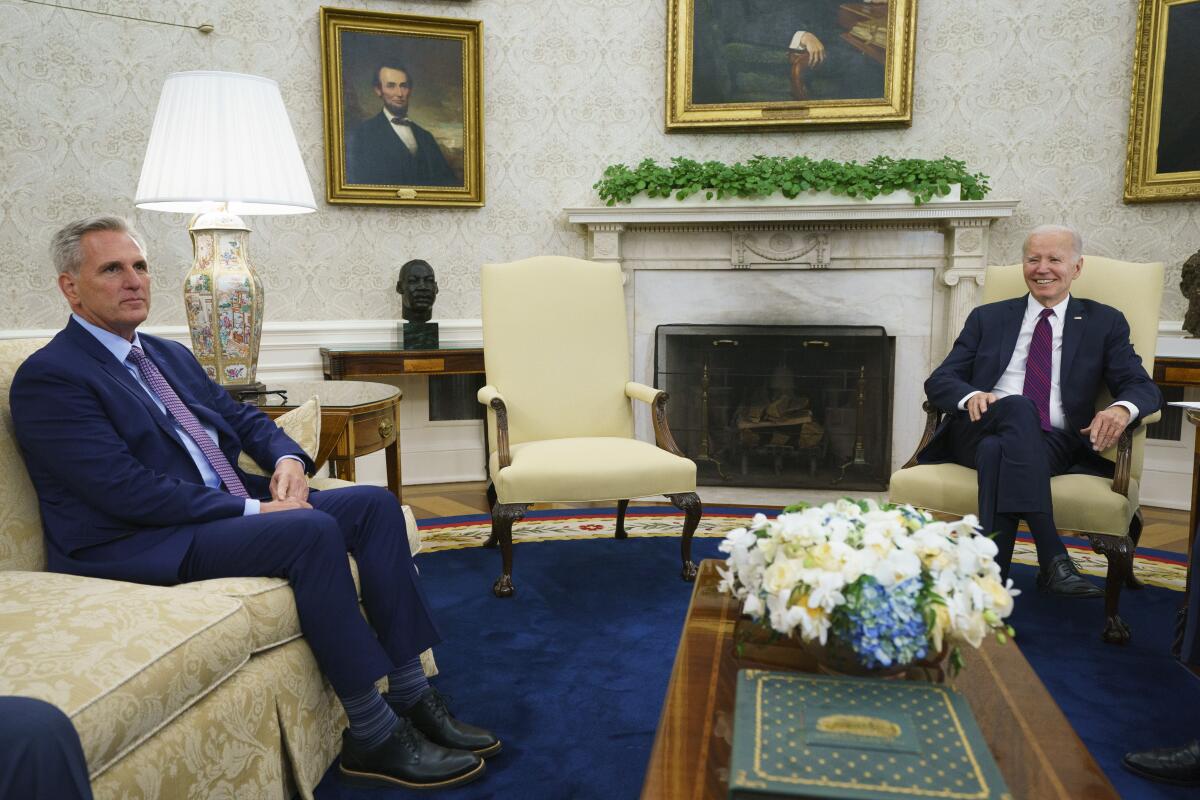

With two weeks left until the national debt ceiling is expected to be reached, precipitating a constitutional and economic crisis, House Republicans continue to insist that President Biden cave in to their threats.

The problem is that if Biden makes any concession as the price of raising the debt ceiling, it will encourage Republicans to take the global economy hostage again and again. After all, their proposal would provide only a short respite from extortion, setting the stage for another showdown less than a year from now.

What happens if Congress fails to raise or suspend the statutory debt limit before the beginning of next month, when the Treasury Department expects to run out of money to cover the nation’s obligations without further borrowing? Conventional wisdom says the president would have to choose which creditors to pay and which to stiff. But the conventional wisdom is wrong.

The Constitution assigns the power to spend money to Congress. Supreme Court cases under Presidents Nixon and Clinton established that a president who fails to spend funds appropriated by Congress unconstitutionally usurps legislative power. Biden could no more fail to pay the nation’s bills than he could refuse to serve as commander in chief of the armed forces.

Yet although it would be plainly unlawful for the president to unilaterally decide not to cover some of the nation’s legal obligations in full and on time — sometimes called “prioritization” — the same can be said of any presidential attempt to raise revenue through taxes or increase borrowing beyond the debt ceiling.

Once we hit the debt ceiling, Biden will bump into a constitutional obstacle no matter what he does. Failing to spend appropriated funds, raising taxes or borrowing money to pay the bills would all infringe on Congress’ constitutional powers. The president would face what we have called a “trilemma” in which all his options are unconstitutional.

Does that mean the president should do nothing? Hardly. It’s not even clear what “nothing” would mean in this context. Not pay the bills? That would amount to unconstitutionally cutting spending. Hide out at his beach house in Rehoboth? That would simply force other executive-branch officials to decide how to encroach on congressional powers.

Even so, a choice has to be made. Comparing household and government finance is often unhelpful, but here it offers some guidance.

Consider a financially distressed tenant who risks eviction if she skips a month’s rent but also must buy gas and make loan payments on the car she needs to get to work. She explores alternatives: Maybe the landlord will cut her some slack; maybe she can ditch the car and take a bus. Even if there is no escaping an unappealing choice, she doesn’t simply give up. Rather, she chooses the least bad option.

The same principle applies to a president: If all his options are unconstitutional, he should choose the least unconstitutional option. So which unconstitutional option — unilaterally raising taxes, disobeying spending laws or borrowing beyond the debt ceiling — is the least unconstitutional? The answer lies in the Constitution’s delicate balance of powers.

The nation’s complex tax and spending laws reflect a vast array of contentious congressional decisions — from how much to spend on childhood nutrition programs to the extent of tech subsidies to the level of assistance to veterans. If the president chose to unilaterally raise taxes, he would confront the question of whose taxes to raise and by how much. If he refused to release the money Congress has appropriated to cover our legal obligations, he would have to decide which bills to pay in full, which to pay in part and which to not pay at all.

Every aspect of these choices would be legislative. The president would become a legislature of one, overriding the compromises and trade-offs that Congress made.

By contrast, violating the debt ceiling would not require the president to make any legislative-style decisions. He would simply instruct the Treasury Department to continue to issue bonds sufficient to cover the shortfall between taxes and appropriations — just as it always does. Borrowing in excess of the debt ceiling is clearly the least unconstitutional option because the president would make only one simple decision instead of leaping into the realm of rewriting multiple laws.

But wait: Might there be a fully constitutional option — the equivalent of selling the car and taking the bus instead? The short answer is no.

Some suggest issuing exotic bonds based on a hyper-technical reading of the debt-ceiling statute. Others propose the administration pay off the debt by minting a multitrillion-dollar platinum coin and depositing it with the Federal Reserve. That would attempt to exploit an extremely dubious statutory loophole while threatening to rattle global markets more than any other option. Besides inviting invalidation by the courts, both the coin and the bonds would probably count as debt and therefore fail to achieve the purpose of avoiding the ceiling.

What about Section 4 of the 14th Amendment, which commands that the “validity of the public debt of the United States … shall not be questioned”? Although some have wrongly suggested Biden could “invoke” that constitutional provision to disable the debt ceiling the way Harry Potter invokes his protective Patronus, the provision does not imbue the president with special powers. It does, however, mean that a president must not fail to pay the nation’s bills and would therefore lead Biden to the same course we are urging.

We wish there were a magic spell to neutralize the debt ceiling. Even without one, however, the president has options. He should choose the least unconstitutional one and continue to meet our national obligations.

Neil H. Buchanan is an economist and law professor at the University of Florida Levin College of Law. Michael C. Dorf is a law professor at Cornell Law School.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.