Vulnerable GOP candidates in the suburbs are torn over whether to run with Trump — or from him

As the midterm elections approach and vulnerable House Republicans nervously navigate around an unpopular president, charting a course is particularly fraught in the suburbs of Philadelphia, where the dominant ideology is pragmatism and fickle voters have little patience for Washington’s political drama.

And it is here that two Republican lawmakers representing nearly adjacent districts, and espousing similar centrist goals, have nonetheless chosen divergent paths to seek victory as representatives of a party now thoroughly defined by President Trump.

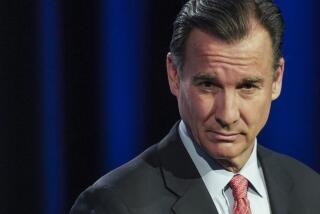

Rep. Tom MacArthur, from a district just over the state line in New Jersey, tilted right as opportunities emerged to ally with Trump, a president still supported by most registered Republican voters. Meanwhile in Pennsylvania, Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick stubbornly kept his distance, taking a lonely course down the middle.

One thing they have in common: both are in political peril.

Their contests are a test case for a Republican Party desperate to hold the allegiance of suburban voters across the country. From the booming communities outside Atlanta to the one-time GOP stronghold of California’s Orange County, incumbent Republicans nationwide face similar dynamics as middle-of-the-line voters rebel against their representatives’ alignment with Trump.

In this part of the country outside Philadelphia, the ranks of suburban swing voters are swelling as Trump’s coalition of disaffected Rust Belt and Appalachian voters stagnates amid demographic shifts and dissatisfaction with his governing style. Many of those swing voters are college-educated Republicans who until Trump would have found it unimaginable to affiliate with any other party, but now are seriously considering it.

Among them is Richard Lipman, 75, a lifelong Republican here who finds MacArthur’s affiliation with Trump unforgivable. “Trump has morally destroyed the country,” Lipman said. “Every day is another disgrace.”

While moderate Republicans have been a diminishing presence in Congress for some time, the trend has accelerated under this unabashedly partisan president. Many suburban Republican incumbents who ran as moderates have chosen to retire; the rest are left to either sit on the sidelines, occasionally breaking with Trump’s agenda, or to share in the credit for policy gains like tax cuts and win the president’s endorsement.

Trump’s habit of attacking lawmakers he considers disloyal intensifies the pressure, especially after the high-profile defeat of one such House member, Rep. Mark Sanford of South Carolina, in a Republican primary.

“Sure, I am, maybe, for a host of reasons, on a couple of big issues in small company” in New Jersey’s congressional delegation, MacArthur said, noting his vote for the tax cuts that every other New Jersey lawmaker voted against, his lead role in the contentious and ultimately unsuccessful effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act, and his championing of a far-reaching expansion of gun rights pushed by the National Rifle Assn.

“I would rather be the guy who can get things done and work with everyone than add to the dysfunction,” he said.

The moves considerably raised MacArthur’s profile. He was invited to take the podium in the White House Rose Garden during Trump’s televised celebration after the House passed the Obamacare repeal bill (it later died in the Senate). Soon after, the second-term congressman, a wealthy insurance executive who has collected considerable campaign cash from insurance and pharmaceutical firms, was feted at Trump’s New Jersey golf club in the first fundraiser the president held for a House member.

While MacArthur says his alliance with Trump has been good for his district, it is not playing well in a big swath of it. The next time he got national attention after the Rose Garden event was for his town hall meeting in heavily Democratic Willingboro, N.J. Some 300 angry voters shouted at MacArthur for five hours straight.

He hasn’t held a town hall since. “I am not interested in doing events that are just a YouTube moment for the resistance,” he said. “I have done tons of other events.”

“When I go to Stafford Diner or Marlton Tavern I don’t have people coming and asking me about Rose Garden speeches and presidential politics,” MacArthur continued. “They want to talk about the joint [military] base in the district and things I have done to preserve that. They want to talk about local things.”

Reflecting MacArthur’s challenges, the nonpartisan Cook Political Report has twice downgraded the congressman’s prospects for holding his seat — from ranking the race a “Likely Republican” win to “Lean Republican” to “Toss Up” within the last four months. A mid-August Monmouth University poll found MacArthur in a virtual dead heat with Democratic opponent Andy Kim, a 36-year-old political neophyte who served on President Obama’s National Security Council as its Iraq director.

“Before Trump, MacArthur really positioned himself as a bipartisan voice,” said Patrick Murray, director of the Monmouth University Polling Institute. “Then he became Trump’s strongest supporter in the delegation. If Trump had remained moderately popular, that would have worked.”

But Trump didn’t, and now MacArthur’s best hope of reelection is by turning out the mostly white, retirement-age voters in his district’s exurbs, beyond the suburbs — residents whose loyalty to Trump may not otherwise extend to showing up for a midterm election when he’s not on the ballot.

Even in the most conservative parts of his district, MacArthur is facing challenges he didn’t two years ago. Take the fledgling Waretown Democratic Club, formed by a group of seniors here driven by antipathy to Trump.

The retirees are packing friends into house parties for Kim in the district’s gated communities. On an otherwise sleepy late-summer Monday, more than 200 voters showed up at a trio of Kim house parties in a corner of New Jersey where Democrats were a nonentity for years.

Many were looking to channel their anger over MacArthur’s Obamacare vote, and Kim obliged, sharing the story of the moment he decided to run. The candidate recalled anxiously sitting in a hospital waiting room last year as he and his wife prepared to talk with a doctor about medical complications facing their soon-to-be-born son. Kim said he tried to distract himself from his worries by watching the news blaring from the hospital television.

“Whose face do I see pop up on the screen?” Kim said. “Who is talking about how he raised this [Obamacare repeal] bill up from the dead with his own two hands and got it passed? It was my own congressman.”

He went on: “I nudged my wife. I told her, if we get through this as a family and our baby is born and we are able to move forward, I promise I will do whatever I can to hold that man accountable for what he just did.”

Across the river in Bucks County, Pa., Republican Brian Fitzpatrick, a former FBI agent, has robbed his Democratic rival of such potent talking points.

Fitzpatrick didn’t vote for the Obamacare repeal. His work on gun control won him the endorsement of gun safety crusader Gabby Giffords. He earned praise — and endorsements — from the AFL-CIO after breaking ranks with Republicans to denounce the recent Supreme Court decision banning compulsory union dues for public sector workers.

Democrats were supposed to have the edge in Fitzpatrick’s turf. The district was recently redrawn as part of a court-mandated redistricting, leaving the one-term Republican incumbent now representing an electorate that narrowly supported Hillary Clinton in 2016.

Yet Fitzpatrick is largely seen as the favorite. His wealthy opponent has failed to catch fire, and Fitzpatrick’s own centrist voting record neutralizes groups on the left — like unions and gun safety organizations — that are going after other Republicans. The Cook Report pointed to this dynamic when it moved Fitzpatrick’s district from “Toss Up” to “Lean Republican” in July.

“As the Republican Party swung to the right on abortion and gun control and all these issues, it has been a huge factor in moving the Philadelphia suburbs away from” the party, said G. Terry Madonna, director of the Center for Politics and Public Affairs at Franklin and Marshall College.

Fitzpatrick has been a rare holdout among Republicans, Madonna said, and it has positioned him for survival in a district that Democrats should otherwise be poised to capture.

Still, more suburban Republicans have taken MacArthur’s Trumpian path. Whether they accept an invitation in the future to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with Trump in the Rose Garden, however, will hinge on whether they survive the November elections that have shaped up, certainly in the nation’s suburbs, as a referendum on his presidency.

The latest look at the Trump administration and the rest of Washington »

More stories from Evan Halper »

evan.halper@latimes.com | Twitter: @evanhalper

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.