Supreme Court appears set to limit protections for company whistleblowers

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — Supreme Court justices on Tuesday sounded ready to bar whistleblowers from suing companies for illegal retaliation under a 2010 law if they’ve only reported wrongdoing internally, and not to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

If so, their ruling, due early next year, could strike down part of an SEC rule that interpreted the law as more broadly protecting whistleblowers, including those who disclosed fraud only to other company officials.

The Dodd-Frank Act, passed in the wake of the Wall Street collapse of 2008, sought to encourage auditors, lawyers and other employees to sound an alarm if they spotted serious wrongdoing. Employers were told they could not “discharge, demote, suspend, threaten [or] harass” anyone for “making disclosures” of potential violations. Employees who were fired could sue and win double back pay if they showed they were victims of retaliation.

But the law also defined a whistleblower as someone who provides information “to the SEC.”

During oral arguments Tuesday in Digital Realty vs. Somers, the justices were quick to say that such a narrow definition leaves out an employee who made only an internal disclosure to company supervisors, or was fired before contacting the SEC.

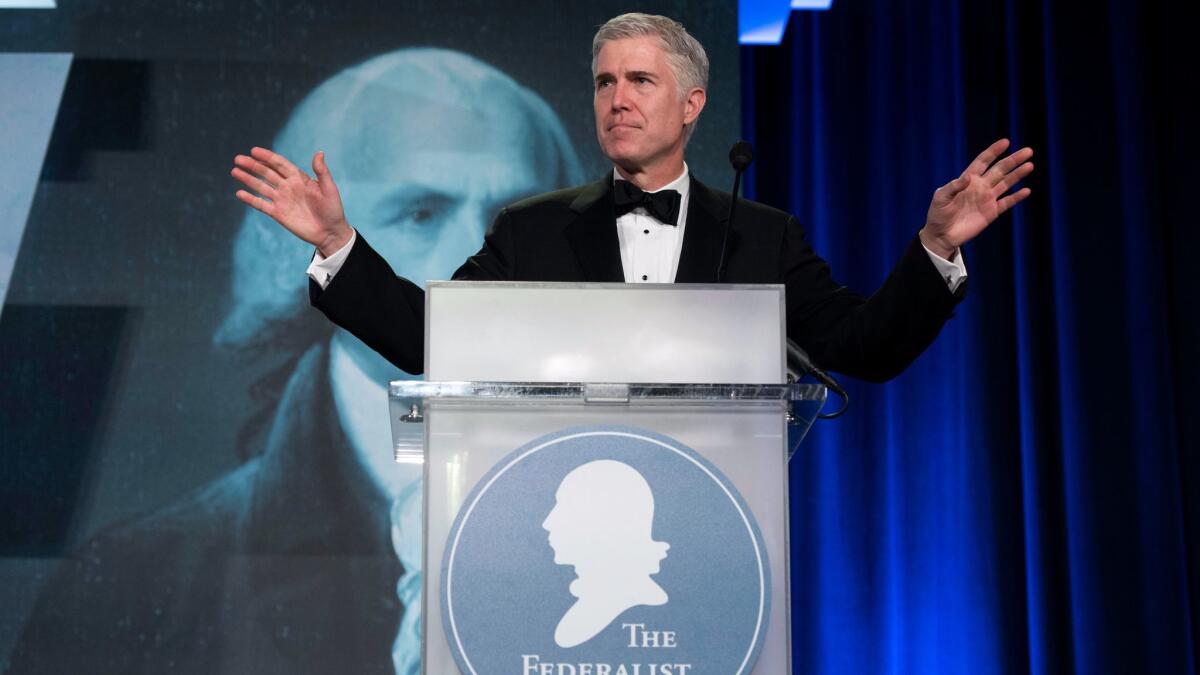

“I’m just stuck on the plain language here. How much clearer could Congress have been?,” asked Justice Neil M. Gorsuch in the first of a series of pointed questions directed at an attorney for a fired whistleblower. The law protects those who “report to the commission. What would you have had Congress do?” he asked.

Gorsuch has insisted that the high court should interpret laws based strictly on their text, not on their broad aims. He voiced surprise and irritation that “we have two circuit courts that actually gave deference” to the SEC’s “unreasoned opinion” extending protection to internal whistleblowers. He was referring to the 9th Circuit Court in San Francisco and the 2nd Circuit in New York, both of which ruled that the intent of the Dodd-Frank Act was to protect whistleblowers, whether they raised concerns with regulators or company officials.

In the case before the court, Paul Somers, a vice president and portfolio manager at Digital Realty Trust in Singapore, says he was dismissed in 2014, weeks after telling senior executives in San Francisco of a possible $7-million cost overrun on a project in Hong Kong. He did not contact the SEC before his firing, or file a complaint afterward with the Labor Department within 180 days, as permitted under another law.

The company disputed Somers’ claims of wrongdoing, and it urged that his suit be dismissed because he was not a protected whistleblower under the Dodd-Frank Act.

But a federal judge in San Francisco and the 9th Circuit cleared the suit to proceed.

Daniel Geyser, a lawyer for Somers, said Congress wanted to protect internal whistleblowers. “Every piece of modern, major whistle blowing legislation” sets out to “protect internal whistle blowing,” he said.

He was joined by Justice Department lawyer Christopher Michel, who was defending the SEC’s rule. “I think it’s quite clear that what Congress was trying to do in Dodd-Frank was to bolster the remedies that were available under Sarbanes-Oxley,” Michel said, referring to the 2002 law that extended protection to employees who file complaints with the Labor Department.

Gorsuch said he was not impressed with that argument. “We don’t follow what they are trying to do. We follow what they do,” he said.

Several liberal justices said they were troubled about leaving internal whistleblowers unprotected, but none voiced support for allowing Somers to sue.

Justice Elena Kagan said the law as written was “quite odd. A typical anti-retaliation provision, you would think, [would say] if I report internally and I’m fired for it, then I get my protection,” she said. “It’s odd. It’s peculiar. It’s probably not what Congress meant. But what makes it the kind of thing where we can just say we’re going to ignore it?” she asked Michel, an assistant to the solicitor general.

Michel said the court in the past has ignored provisions that would make “a pretty big mess” of the law. “I’m not saying that it couldn’t have been written more clearly,” he added.

“I think it was written very clearly,” Gorsuch interjected.

Major questions before the Supreme Court this fall »

On Twitter: DavidGSavage

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.