Not since Bork has a Supreme Court pick had such a public record on issues. Will it matter for Barrett?

As a law professor, Elena Kagan once described Supreme Court confirmation hearings as a “valid and hollow charade,” because modern-day nominees rarely reveal their views on issues to avoid compromising their impartiality in future cases.

Then, in 2010, as a nominee by President Obama to the Supreme Court, that’s exactly what Kagan did, too.

But Judge Amy Coney Barrett may have more trouble doing so. Unlike any Supreme Court pick since the failed nomination of Robert Bork, Barrett has taken a public stand on the most divisive issues before the court, including abortion, contraceptives, guns and healthcare.

That’s in stark contrast to the past three decades of Supreme Court nominees, whose public records did not include comments on hot-button issues that could prove troublesome in a Senate confirmation hearing.

As a Notre Dame law professor, Barrett signed a public letter in 2013 that condemned the “Supreme Court’s infamous Roe vs. Wade decision” and called for “the unborn to be protected in law.” In 2006, she signed on to an ad that called for an “end to the barbaric legacy of Roe vs. Wade.”

After being appointed to the 7th Circuit Court, she joined a dissent that called for reconsidering a blocked Indiana law that would have banned abortions based on a disability or deformity. She also voted in dissent to strike down the laws taking guns away from felons if their crimes did not involve danger or violence.

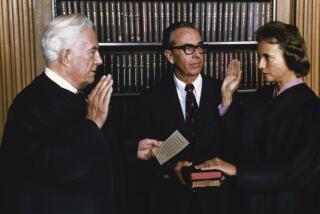

Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation hearing begins before the Republican-led Senate Judiciary Committee.

And when the Supreme Court narrowly upheld the Affordable Care Act over a dissent by Justice Antonin Scalia, Barrett — who once clerked for Scalia — said she thought her former boss had the better argument.

Some legal experts say Barrett may have opened the door to more probing questions because she has gone on record. That grilling could begin Tuesday, during the second day of her Senate confirmation hearing.

“This nomination is likely to be more like Bork’s than [Justice Brett M.] Kavanaugh’s in terms of the examination of her record,” said Lori A. Ringhand, a University of Georgia School of Law professor and co-author of a 2013 book on Supreme Court confirmations. “Judge Barrett, like Judge Bork, has a pretty extensive history of writing and speaking on controversial issues. She will be pressed on those issues. I think that’s a good thing. Hearings that focus on the constitutional consequences of a nomination are one of the ways we understand over time what is and is not in the constitutional mainstream.”

However, unlike Bork, whose 1987 nomination was derailed by his willingness to frankly discuss his views on civil rights, voting rights and abortion — both before and during his confirmation — Barrett appears almost certain to be narrowly confirmed. Republicans abolished the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees, so they can confirm Barrett with just 50 votes and no Democrats.

In his opening statement at Barrett’s confirmation hearing, Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) appeared to invite probing questions, calling it an opportunity “to dig into her philosophy” and her views of the law.

But it is not clear the Democrats want to spend much time debating abortion and the future of Roe vs. Wade. On Monday, they focused on the healthcare law and what it would mean to tens of millions of Americans if the high court were to agree with President Trump’s lawyers and strike down the entire law.

Republicans appeared poised to argue that questioning Barrett about issues like abortion and contraceptives is attacking her religion. If Barrett is asked about abortion, she is likely to respond generally by saying it is a long-standing precedent of court, the language used by most nominees.

Because of the sharp partisan divide, University of Chicago law professor David Strauss expects that the hearings will not reveal much about Barrett’s views of the law or precedent.

“If confirmation hearings were pretty much an empty ritual a decade or so ago, they are really empty now, because it’s all become so much more partisan and polarized,” he said.

In decades past, at least some senators on the Judiciary Committee were publicly undecided when the hearings got underway.

“It used to be that what a nominee said — and, more important, how the nominee came across — could give a senator cover if he or she wanted to vote against the nominee but didn’t want to seem partisan or disrespectful of the president’s prerogatives,” Strauss said.

In 1991, Clarence Thomas was believed to have the backing of most senators when his hearings got underway. But he dodged questions over several days, and the Democratic-led committee — under then-chairman Sen. Joe Biden — split 7-7. His nomination went before the full Senate after a second round of hearings based on Professor Anita Hill’s allegations of sexual harassment, and Thomas was confirmed on a 52-48 vote.

In the decades since, presidents have selected well-qualified nominees who had steered clear of controversy. President Clinton’s two nominees — Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer — had spent more than 13 years on U.S. appeals courts and were described then as moderate liberals.

President George W. Bush’s two nominees — Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. — were seen as conservative judges who kept their views to themselves. Obama nominated Judge Sonia Sotomayor, who had 17 years on the bench, and Kagan, a former Harvard Law dean who was then serving as U.S. solicitor general. Neither had sounded off on legal controversies.

The same was true with Trump’s first two nominees: Justices Neil M. Gorsuch and Kavanaugh. Both had served as appeals court judges and drew criticism for some conservative rulings. Despite caustic questions from some Democrats, neither revealed much more about their views on the law beyond what they had said before they were nominated.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.