Reading Ruben Salazar

He was no radical. He was a prophetic reporter

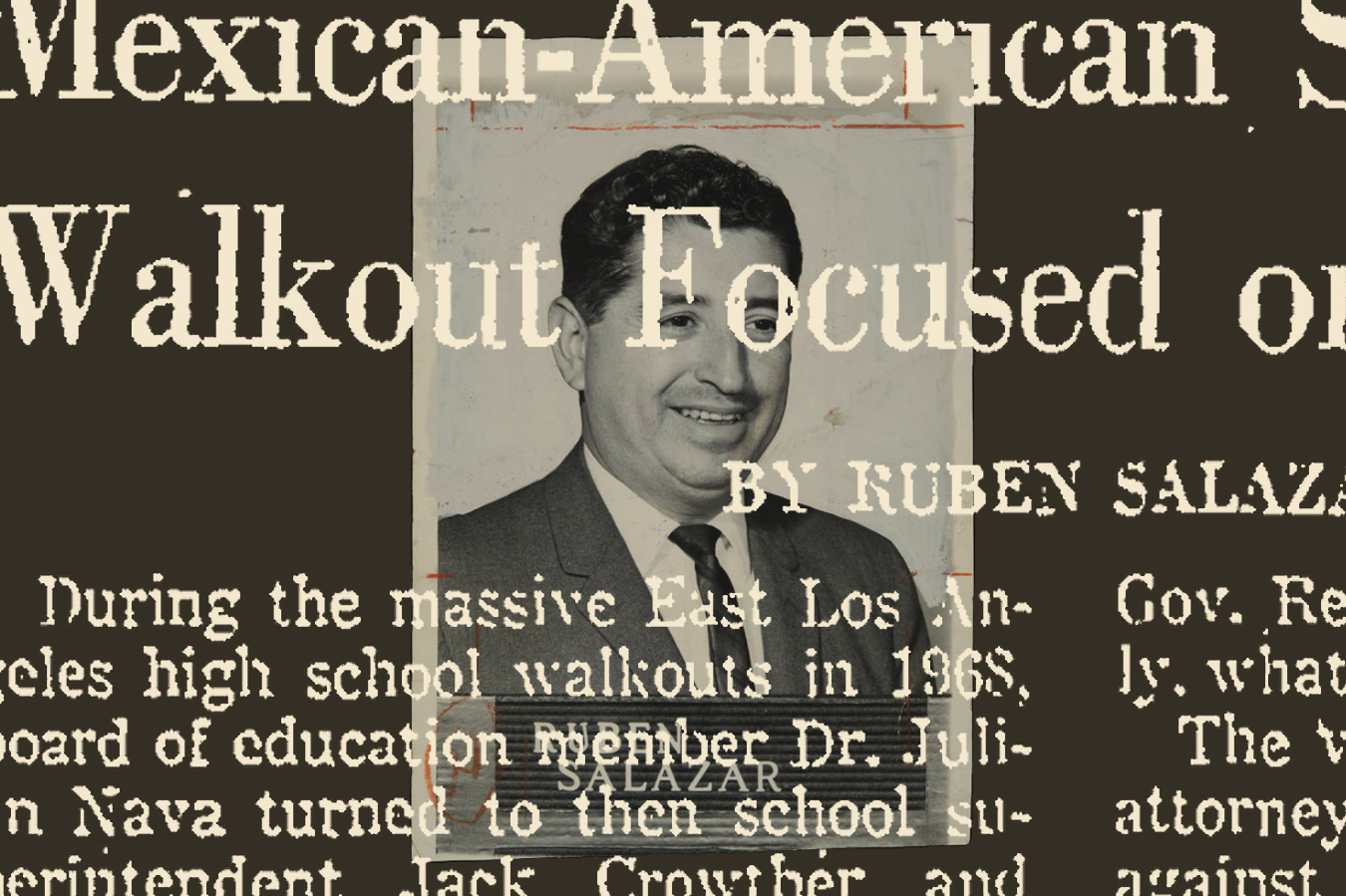

About 20 years ago, I visited a Chicano bookstore in Santa Ana to buy “Border Correspondent,” a greatest-hits compilation of pioneering Los Angeles Times writer Ruben Salazar.

I was a senior at Chapman University, a film major with no journalistic aspirations but who was trying to learn how to be a Chicano. A friend had passed along Salazar’s essay “Who Is a Chicano? And What Is It That a Chicano Wants?” — a bolt of literary lightning on par with Corky Gonzales’ “I Am Joaquin” and “El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán” by Alurista, and a foundational text of Chicanismo.

I wanted more.

“Border Correspondent” was a quick, easy read, with an introductory essay by editor Mario T. Garcia that places Salazar in his time; photos from his home and professional life; and selections that range from lurid jailhouse exposés in Salazar’s hometown of El Paso to dispatches from the U.S.-Mexico border and articles from abroad.

But the bulk of the entries are set in Southern California, where Salazar covered the burgeoning Chicano movement as a reporter and columnist until Aug. 29, 1970 when a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy fired a tear-gas canister that struck Salazar’s head, instantly killing him.

The book is one of the few easily available ways to read Salazar’s work, even in this Internet age, and it remains in print. But after finishing the Salazar collection the first time, I felt disappointed.

All that hype, for this?

Here was no radical, I felt; Salazar was just a by-the-numbers scribe.

His throughline — Chicanos are misunderstood, angry and discriminated against — struck me as unoriginal. The writing seemed labored, explanatory, geared toward a gabacho audience.

His death was a tragedy. But that Chicano activists lionized him decades after his passing only reaffirmed for me that too many people never bother to learn what their heroes actually did.

My copy of “Border Correspondent” ended up becoming a gift for someone else.

The Times is taking a look back at the legacy of the Chicano Moratorium in 1970. See more stories

All these years later, with a journalism career longer than Salazar’s and finally a bit of wisdom in my head, I now see my error.

I was looking for Salazar the revolutionary, when Salazar the reporter was even more radical.

“Los Angeles had become Chicano under our nose without us realizing it,” said William J. Drummond, professor at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism and one of the first Black reporters ever hired by The Times. He was in his mid-20s when Salazar returned to Los Angeles in 1969 from a plum Mexico City post, and the two were lunch buddies with a group of colleagues. “Ruben understood the fault line that existed, and let his career follow that. There was no road map. But he was creating it.”

Now, I see a journalistic John the Baptist. A voice crying out in the white wilderness that was the Los Angeles Times in the 1960s, making way for better coverage of Latinos to come — and for more Latinos to cover them.

If you love Los Angeles, support our journalism.

The Times is dedicated to covering everything about our city, whether taking a hard look at its past or at what's going on today. Get unlimited digital access. Already a subscriber? Your contribution helps us make projects like this possible. Thank you.

Salazar notched nearly every milestone that a reporter seeks in a career — overworked newcomer, trusted beat reporter, valued correspondent, must-read columnist, even television news director — as a Mexican American, at a time when the number of Latinos at the L.A. Times was no more than four. His writings are like a Chicano version of the Gnostic Gospels, one Salazar knew he was drafting all by himself.

On Jan. 18, 1969, he gave a speech at a San Antonio conference held by the U.S. Department of Justice to examine how media depicted Mexican Americans. Four days earlier, Salazar had filed his first story for his new Chicano assignment.

“There is really little to say about the Mexican American beat in the past except that it did not exist,” the Timesman drolly noted. “Mexican Americans traditionally kept their place so why should the big, important news media take notice of them?”

The reporter behind the legend

Reading Salazar today, my initial opinion of his skills still somewhat stands.

“He didn’t write sentences that I would relish,” admitted Drummond, and while the assessment seems harsh, it’s borne out by the clippings found in “Border Correspondent.”

Salazar’s style could be languorous and heavy-handed. In an award-winning seven-part 1963 series about Latinos in Los Angeles, he deemed East Los Angeles and surrounding Latino cities and communities the “Serape Belt,” a cringe-inducing phrase and one obviously written for a laugh from non-Mexicans.

As a columnist, Salazar’s righteous fury trips over dry prose and attempts at cleverness.

“The Los Angeles Latin press corps took Police Chief Ed Davis out to dinner the other night,” he wrote in a March 13, 1970, column. “The enchiladas were good but the conversation left both sides hungry for understanding.”

This is a wholly uncharitable take, I admit — and it’s also unoriginal. We remember him not for what he wrote but for what he showed.

The topics Salazar covered nearly 60 years ago read like the headlines your woke friends post on Facebook today. A 1964 gentrification battle in Santa Fe Springs. Progressives vowing to leave the Democratic Party. Tensions between Chicano and Black communities. Immigration, health and education disparities among Mexican Americans.

Salazar was comfortable among politicos and Brown Berets, cholos and businessmen. He wrote about alienation and assimilation — the two grand ghosts of the Mexican American experience — better than any academic or novelist, by simply holding a mirror to Chicanos and reflecting their image to the world.

That dexterity and profundity made Salazar a must-read long before his death, according to Juan Gomez-Quiñones. The retired UCLA Chicano studies professor first read him in 1968 as a nascent profe.

“His concerns about local issues were informed by national and international contexts” in a way not even the Chicano underground press was able to pull off, Gomez-Quiñones said.

It’s the reporter, not the legend, that Gomez-Quiñones, Drummond and Garcia have taught in their respective classes for decades. To them, Salazar is as important a figure of American journalism as Hunter S. Thompson, Ida B. Wells, Craig Claiborne and other titans who created new genres.

“He was the utmost professional journalist, and as a role model for journalists, that was his legacy,” Drummond said. “I’ve taught Ruben’s writings for 37 years. This was the paragon of professionalism. Someone surrounded by the struggle, but he was there to record it.”

Garcia, a UC Santa Barbara Chicano studies professor, is perhaps the best assessor of Salazar’s talents. He compiled “Border Correspondent” to commemorate the 25th anniversary of Salazar’s killing and is one of the few people to read an unpublished roman à clef that Salazar wrote in the 1960s that remains in the possession of his children.

Hear more from Times journalists. Watch our forum

The Times hosted a virtual forum on the Chicano Moratorium that featured authors of the series, including Daniel Hernandez, Carolina A. Miranda and Robert J. Lopez. Watch recordings via The Times Facebook page, YouTube or Twitter.

“He had different voices,” Garcia said. “Part of his search for his identity is his own search for who he was as a journalist, and part of that struggle [was] what it meant to be a Mexican American journalist.”

I read “Border Correspondent” again recently, and can now respect an adventurous reporter trying things: a bit of first-person new journalism while covering an American military occupation of the Dominican Republic. Straightforward he-said/she-said accounts mixed with open skepticism about the Vietnam War. Columns that would appear in the op-ed section on Fridays, the same day as William F. Buckley, and that were starting to get tighter and better until Aug. 29, 1970.

And there’s still so much to uncover. My colleague Ben Welsh has put together an online archive of some of Salazar’s stories and columns from 1970, the year he died. But my favorite Salazar piece is an Oct. 21, 1962, story titled “Case History of a ‘Rumble’ — Who’s to Blame?,” a study of a brawl between white and Mexican gangs in Pico Rivera.

Instead of treating it like a repeat of the sensationalist coverage The Times gave the Zoot Suit riots in the 1940s, Salazar showed how law enforcement had yet again demonized Latino youth while letting the white teens get off.

“It’s been 50 years since he was killed, but Ruben still seems to fascinate and interest people,” Garcia concluded. “It’s because that aura of him being this movement martyr. But it’s his history as a professional reporter that we need to remember, and he was a darn good one.”

After years as a reporter, bureau chief and foreign correspondent, Ruben Salazar started 1970 with a new assignment: Columnist.

Over the next eight months Salazar produced a remarkable string of writing for The Times, until his life was suddenly ended at a protest march on Aug. 29.

The columns he produced during that period have been published online for the first time to mark the 50th anniversary of his death. You can find them all below.