Check out Cassini’s jaw-dropping discoveries of Saturn’s moons

Saturn is famous for its rings, but more than 60 moons orbit the planet as well. The lunar lineup includes some of the most intriguing worlds in the solar system, including two that are promising candidates in the search for life beyond Earth.

Thanks to NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, we know more about Saturn’s moons than ever before. The spacecraft even discovered more than half a dozen moons during its 13-year tour around the planet.

TITAN

Scientists’ interest in Titan was piqued in the early 1980s, when Voyagers 1 and 2 sent back data revealing a complex chemistry in the moon’s atmosphere. Unfortunately, the twin spacecraft were not equipped to see beneath Titan’s haze.

For decades, Saturn’s largest moon looked like little more than a fuzzy orange ball.

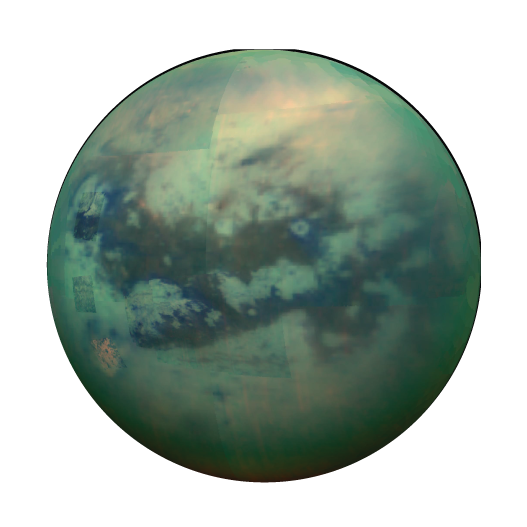

That changed over the course of Cassini’s mission. Using its Visual Infrared Mapping Spectrometer, the spacecraft was able to take a closer look.

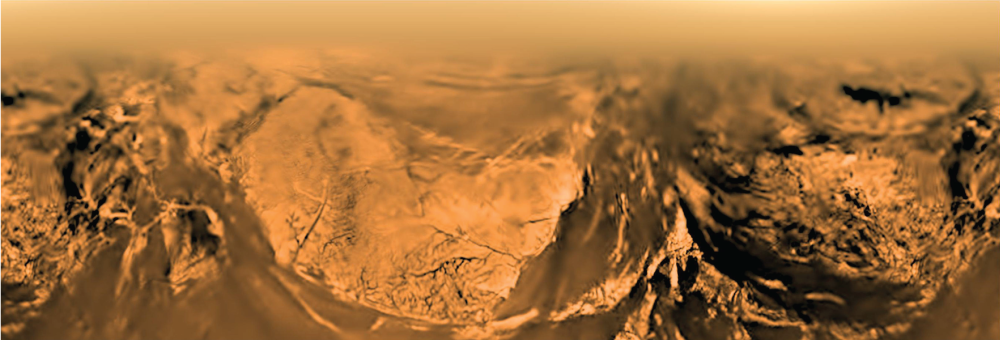

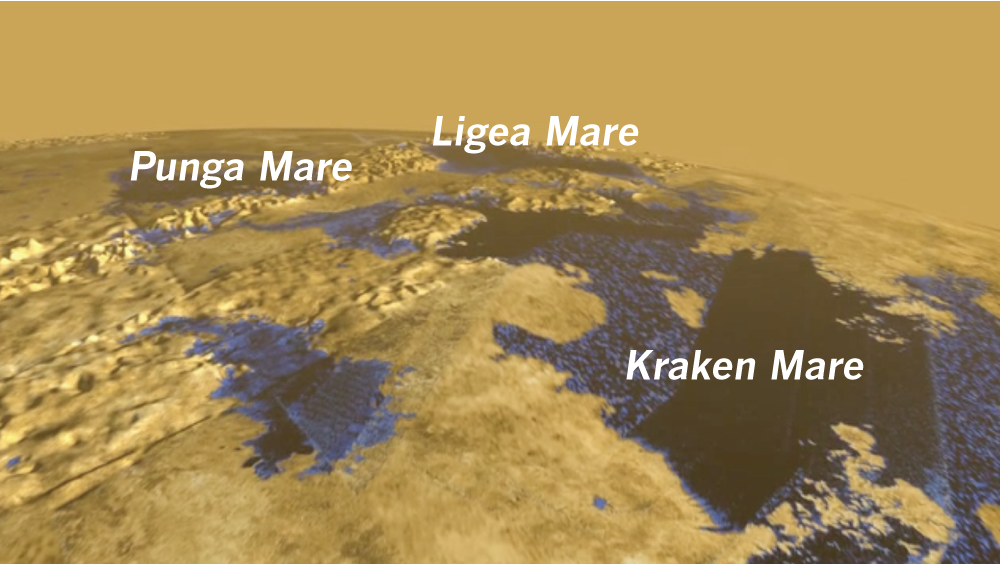

Cassini revealed that the Mercury-sized moon has vast deserts of rippling, sandy dunes at its equator...

...and seas of liquid methane and ethane at its poles.

It appears to be the only other place in the solar system that has a liquid cycle like we have on Earth. But on Titan, rain is made of methane rather than water.

Titan’s complex chemistry

In Titan’s atmosphere, solar energy prompts nitrogen and methane to react, producing a wealth of organic molecules.

The heaviest of these molecules can fall to the ground and wind up in Titan’s methane lakes and rivers. Other molecules make their way to the surface via rain.

Soluble molecules dissolve in the liquid methane, while insoluble ones tend to sink to the sea floor.

ENCELADUS

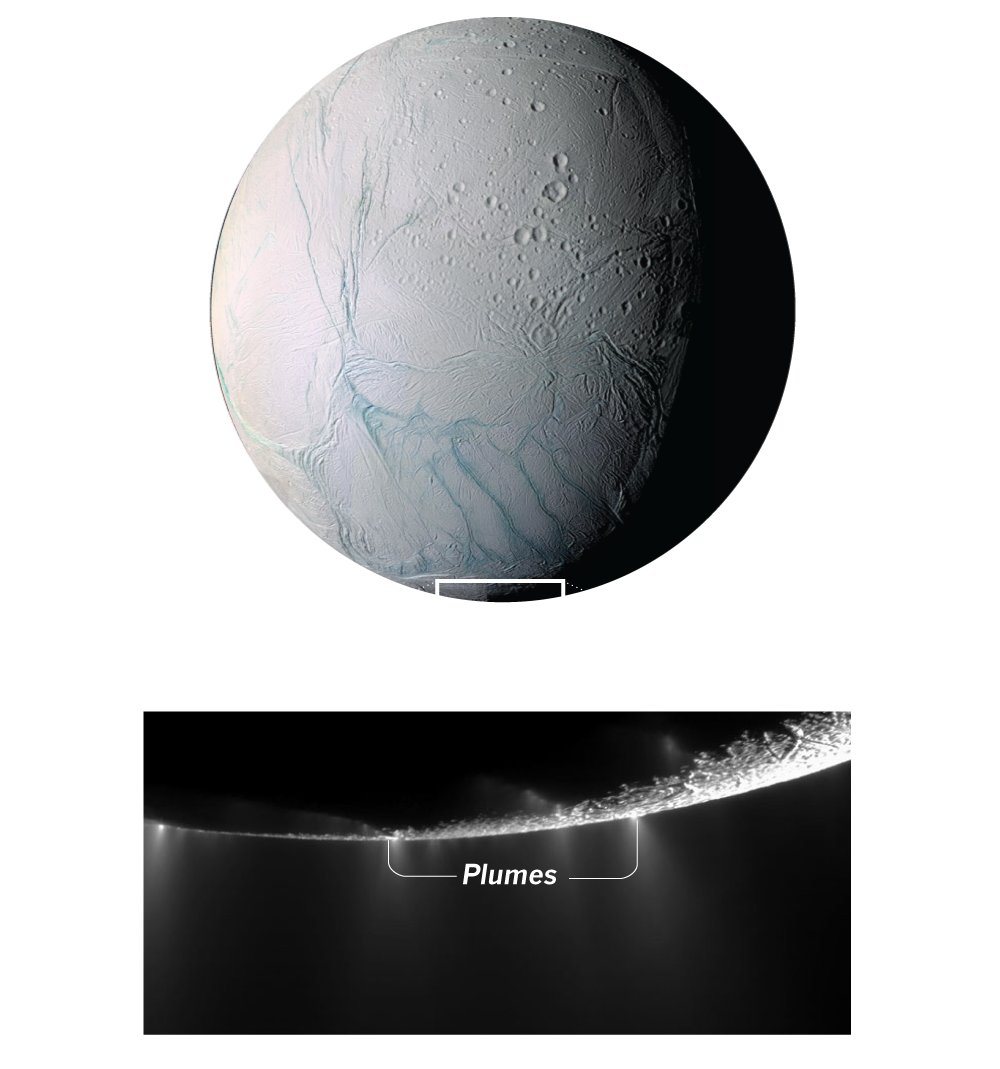

Before Cassini, scientists could see that the surface of Enceladus was unusually bright. But they didn’t know why. Cassini provided a shocking answer: The small, frozen moon has geyser-like jets that spew water and ice particles from an underground ocean out into space.

Some of the material in these plumes lands on Enceladus, helping to keep its surface smooth and bright. One of Saturn’s vast rings, the E ring, is also made up of material from the plumes.

Enceladus’ hidden ocean

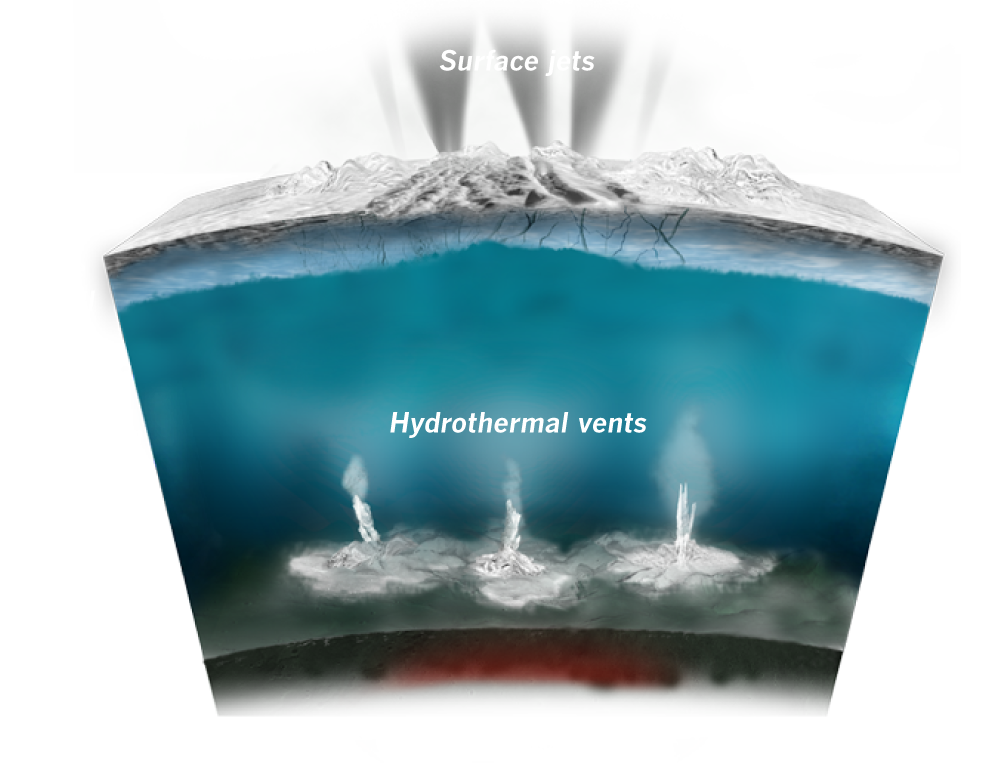

In 2008, Cassini sampled one of the Enceladus plumes and detected nanoparticles that can be generated only when liquid water and rock interact at temperatures over 200 degrees Fahrenheit. That discovery suggests there might be hydrothermal vents on the bottom of the moon’s hidden ocean.

If so, the moon could be hospitable for life.

MIMAS

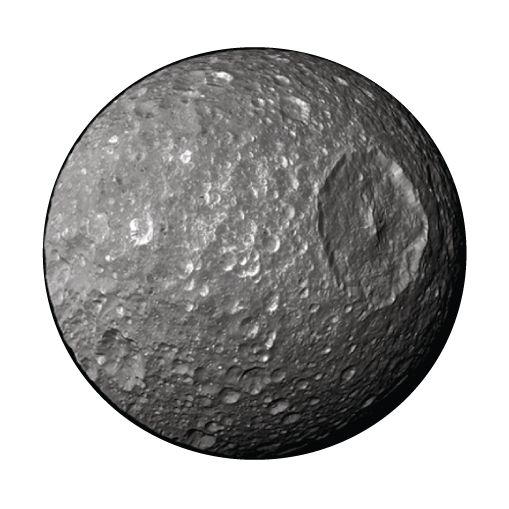

Meet Mimas, the “Death Star” moon. The 246-mile-wide moon has an enormous, 88-mile-wide crater that makes it resemble the planet-destroying space station from “Star Wars.”

An analysis of data collected by Cassini indicates that Mimas wobbles more than it should. Researchers have identified two possible causes of this unexpected behavior. It could be that Mimas has a football-shaped core, or it could have a subsurface ocean like Enceladus.

DIONE

Orbiting Saturn at about the same distance that our own moon orbits the Earth, Dione continues to mystify scientists.

In 1980, the Voyager mission revealed that one hemisphere of the 349-mile-wide moon was covered in bright wispy features. At the time, scientists wondered if the wisps represented deposits of bright materials – snow or deposit from an ice volcano – that had perhaps erupted from the moon and then fallen back to its surface.

Cassini proved that theory wrong. The space probe discovered that the wisps were in fact bright ice cliffs that rose hundreds of feet high.

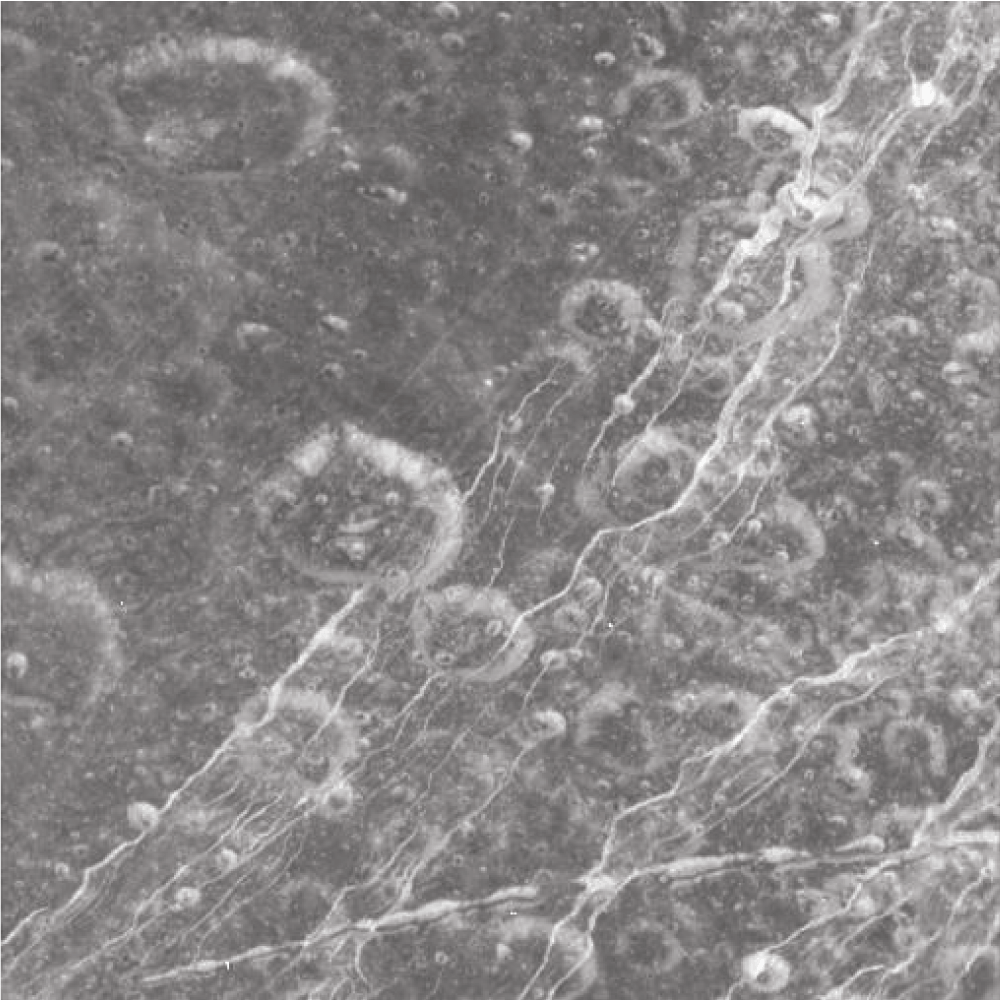

HYPERION

Hyperion is the largest non-spherical moon in the solar system. Shaped like a potato, it’s 204 miles long and has an extremely strange surface that resembles a natural sponge.

IAPETUS

There’s a reason Iapetus has been nicknamed the “Yin and Yang” moon: One hemisphere is almost as dark as coal, while the other hemisphere is nearly as light as snow. This split had confounded scientists for centuries, but Cassini helped them figure out how it came to be.

Iapetus is tidally locked to Saturn, just like our moon is to Earth. That means the same side of Iapetus is always out in front as it travels around the ringed planet — and that’s the side that accumulates debris as it orbits while the other side remains more pristine. (It’s just like when you’re driving in the rain and your front windshield hits more raindrops than your rear window.)

Where is that debris coming from? The Phoebe ring, a super-wide band of dust that extends far beyond the rest of the Saturnian system.

That’s just the first part of the story. In a process known as thermal segregation, the darker side of the moon absorbs more heat, which causes icy particles to transform into a gas. Meanwhile, particles landing on the brighter side freeze, adding to the ice. Both processes accentuate the difference between the yin and yang sides of Iapetus.

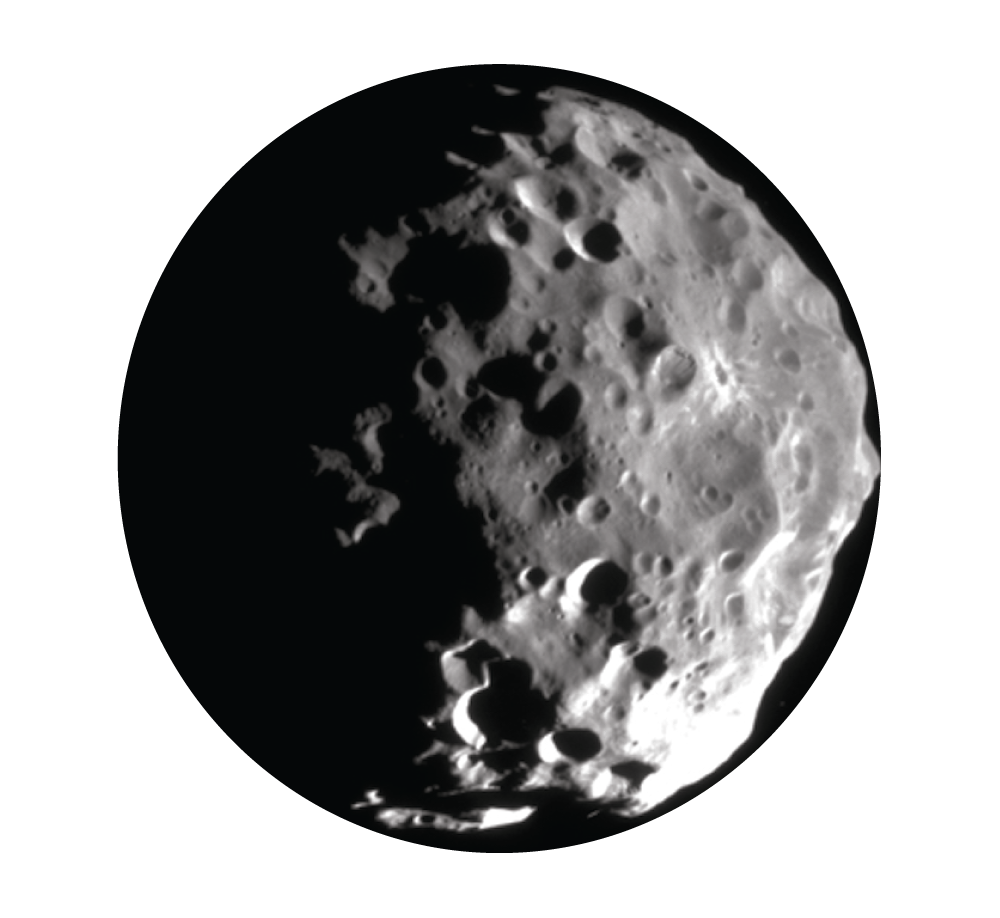

PHOEBE

Phoebe was the first object Cassini encountered when it entered the Saturnian system. It orbits Saturn at a distance of more than 8 million miles. That puts it about four times farther away than Iapetus, the next-most-distant sizable moon.

This oddball moon is one of Saturn’s darkest, absorbing all but 6% of the light it receives from the sun. Adding to its mystique is the fact that it’s in a retrograde orbit, which means it orbits Saturn in the opposite direction of most of the planet’s other moons.

These irregularities suggest that Phoebe may be a Centaur, a primordial object from the solar system’s early days that originated in the Kuiper belt and later migrated toward the inner solar system, where it was captured by Saturn’s gravity. If this theory turns out to be correct, that means Cassini’s observations of Phoebe represent scientists’ first chance to study a Centaur.

“PEGGY”

Let’s call this one the moon that might be. In 2013, already nine years into its tour of Saturn, Cassini spotted a bright bump at the edge of the planet’s A ring that had not been there before.

Further analysis revealed that this disturbance might be caused by an object whose gravity was acting on the surrounding ring particles. Scientists continued to watch over the years as the bright bump came in and out of view. They are still not sure if they caught a moon in the act of forming, a moon in the act of dying, or perhaps something entirely different.

DISTANCE FROM SATURN

Saturn’s vast network of rings and moons circle the planet from distances as great as 8 million miles away. Relatively close-in moons like Enceladus and Dione take just a few Earth days to complete a single orbit around the gas giant. On the other hand, Saturn’s most distant moon, Phoebe, requires 550 Earth days to make its way once around the planet.

The moons’ distances from their host planet are measured as multiples of Saturn radii, which is about 72,000 miles.

Sources: Times reporting, images courtesy of NASA, JPL