Groundwater helps sustain local communities amid drought

Area cities tap local groundwater through rules set by a decades-old legal decision.

While parched Californians have more recently been looking to the skies for some relief from the ongoing drought, for more than a century, locals have dug just below the earth’s surface to tap into valuable underground reservoirs.

Around 30 million Californians rely on groundwater for at least a portion of their supply, and some cities and agencies are entirely dependent on it as a source.

In 2014, groundwater accounted for 46% of Burbank’s water supply and 26% of Glendale’s, according to annual reports by each city’s utility.

“We’ve shifted to a local supply and that’s what’s really sustained us,” said Marsha Ramos, a former Burbank mayor and the city’s current representative on the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California board of directors.

On average, groundwater accounts for about 40% of the state’s water supply, for both agricultural and urban use. However, that number has soared to as high as 60% during the drought.

Until recently, some parts of the state, particularly in agricultural Central Valley, groundwater was pumped unabated, without sufficient recharging — more water was being taken out of the ground and not enough was being put back in, either by man or nature.

In addition to dangerously low groundwater levels, overpumping has also caused some sites to actually sink, with some areas of the Central Valley reporting a drop of 5 to 10 inches , according to a Department of Water Resources report.

Legislative response

All this prompted Gov. Jerry Brown to sign a historic trio of bills last September that make up the state’s first-ever, large-scale groundwater management plan.

The legislation focuses on the previously unregulated Central Valley, since many urban water users have long regulated themselves. Locally, that is the result of a 36-year-old court decision.

“The actions of the state had to do with the Central [Valley],” said Bill Mace, assistant general manager at Burbank Water and Power. “The state was doing ho-hum for us because we were already regulated.”

That regulation stems from a 1979 court decision, when the more than two-decade-long legal battle came to an end. The dispute – between local cities over groundwater ownership — ended with the establishment of the Upper Los Angeles River Area, which is made up of four groundwater basins: the San Fernando, the Sylmar, the Verdugo and the Eagle Rock basins.

The court judgment also established water rights for the agencies that draw from ULARA: the cities of Burbank, Glendale, Los Angeles and San Fernando and the Crescenta Valley Water District.

The San Fernando Basin

“The groundwater situation in the San Fernando Basin is so different because of the judgment,” Mace said. “It’s not the wild west. It’s not pump what you can.”

The San Fernando Basin — by far the largest of the four, spans 112,000 acres and makes up 91.2% of the groundwater fill in ULARA — serves Burbank, Glendale and Los Angeles.

Although Burbank and Glendale do not have ownership rights to the water beneath them, the 1979 decision allowed them to pump a portion of the water they distribute from groundwater. Still, historic drought conditions have meant that some of the same issues that plague the Central Valley have afflicted local supplies.

Across all four ULARA basins, 83,419 acre-feet of water was extracted in 2012-13, according to the last annual report. But less than 5% of that figure was returned to those basins by way of rainfall or other natural sources.

“That tells you the state of affairs, what we’re needing to do in a time of a drought,” Ramos said. “Every drop counts.”

Groundwater contamination

Local water agencies must also deal with the consequences of decades of industrial flow and dirty runoff that has percolated into the underwater aquifers.

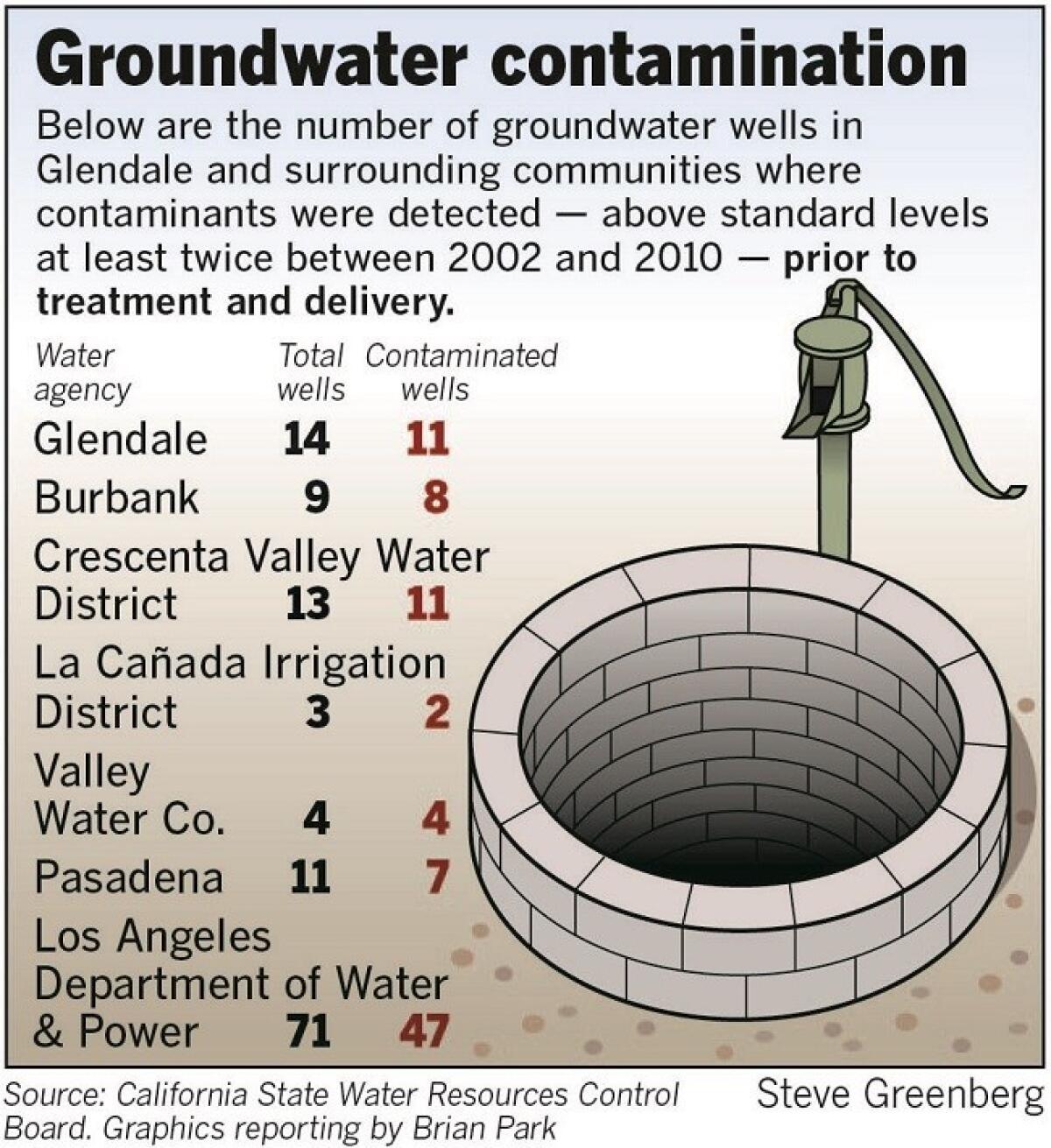

Between 2002 and 2010, eight out of nine groundwater wells in Burbank registered above standard levels of contaminants at least twice. The results were poor in Glendale and the Crescenta Valley Water District as well, where 11 out of 14 and 11 out of 13 wells were also contaminated, respectively.

Contaminated water is treated before it is delivered to water customers. When it comes time to recharge the basin, however, Mace notes that the water being put back in is cleaner, purifying the entire basin.

Ramos said this bodes well for the future.

“We become more efficient in our planning process,” she said. “Water is going to be cleaned up to a greater extent every decade.”

Crescenta Valley

The neighboring Crescenta Valley Water District sources far more of its water from below the soil — about 60% — from the 250-foot-deep Verdugo Basin.

Since the drought began in 2011, there has been “a significant decrease in water levels,” in the basin, said David Gould, district engineer for the Crescenta Valley Water District.

“If the drought continues in the next year or two, we’ll see less water produced from the groundwater. We’ll probably have to import more water from Metropolitan Water District,” he said. “However, by everyone reducing their water use, it’s been helping to conserve our local water.”

The water district’s newest well, located at the Rockhaven Sanitarium site, will begin pumping water in October.

The water district is also looking into pumping water from a well located at the corner of Lowell and Honolulu avenues, which hasn’t been in use since 1976. But that well could begin operating by fall of 2016, Gould said.

Of the 12 wells in the Crescenta Valley Water District, the 10 that are currently active are only part of a larger focus for capturing more groundwater.

Gould said water officials are studying whether it would make sense to lay large pipes, known as infiltration galleries, 10 feet below ground at Crescenta Valley Park to capture water from the Verdugo Wash.

If the study suggests a favorable outcome, Gould said the district would apply for a $3 million grant from the state to install the pipes sometime in 2016.

In the meantime, he said, the reduction of water used for outdoor landscaping helps keep demand down.

“Conserving water is a big deal,” he said, adding later, “We’re just hoping for some rain.”

Glendale

In Glendale, where there are 11 active wells out of 14 total, Glendale Water & Power purchases 70% of the water it needs through the Metropolitan Water District.

The remaining 30% of water is sourced through local wells that tap into the Verdugo and San Fernando basins.

The drought has negatively impacted the local source for water, creating a “plateau effect” on local water production, said Steve Zurn, general manager of Glendale Water & Power.

While the city isn’t looking to building any new wells, it is considering the possibility of rehabilitating older, existing wells in Verdugo Park, in addition to utilizing more recycled water and capturing storm water run off.

“We are looking at all options available in regards to the potential to produce more water locally,” Zurn said.

The uncertainty of the future of the drought has brought to light that groundwater is a regional issue that will require a joint effort, according to Ramos.

“It’s always been a power struggle, water rights have … but this drought has been pushing people to reevaluate and reexamine.” Ramos said. “The drought has forced collaboration.”

--

Kelly Corrigan, Times Community News

Follow Kelly on Twitter: @kellymcorrigan

Brian Park, Times Community News

Follow Brian on Twitter: @TheBrianPark