UCLA set football program in motion with upset win over Nebraska in 1972

James McAlister had two great runs on a dream-like night 40 years ago.

One was a 30-yard gain on UCLA’s first play from scrimmage. The other was a sprint across the Coliseum floor to the locker room following the Bruins’ 20-17 upset of Nebraska, which had come into the game as the top-ranked team in college football.

“I normally walked off the field,” said McAlister, now 61 and the track and field coach at Charter Oak High. “We sat around the locker room thinking, ‘We just beat the No. 1 team in the nation.’ ”

The Cornhuskers, who were two-time defending national champions, came west toting a 32-game unbeaten streak. They left stunned after a loss to Bruins team that had a 2-7-1 record the previous season.

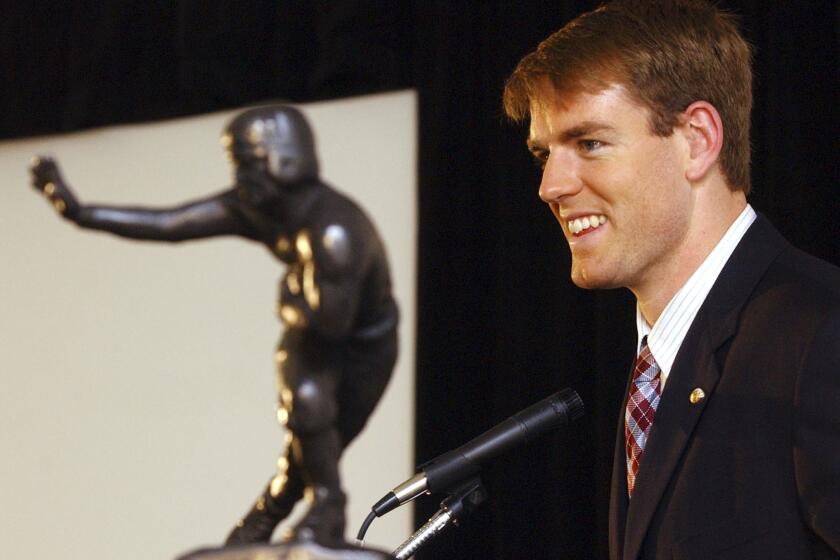

There was plenty of star power in the game, including Nebraska’s Johnny Rodgers, who went on to win the Heisman Trophy that season, and UCLA’s Mark Harmon, who went on to be a two-time Emmy-nominated actor.

In the end, it was a 30-yard field goal by Efren Herrera with 22 seconds left that tilted the college football landscape.

“I remember the focus on the program changed,” said Harmon, who stars in the hit television series “NCIS.” “Sports Illustrated sent Dan Jenkins out to do a story on us.”

And he remembers running like McAlister … after the game.

“I put my chin strap in my pants, because I didn’t want to lose it with all the people on the field,” Harmon said. “By the time I got back to the locker room, I barely had my shoes on.”

It was arguably UCLA’s greatest football victory outside of its rivalry with USC, and memories are flooding back this week as the Bruins prepare to play Nebraska on Saturday at the Rose Bowl.

Nebraska has not won a national title since 1997, but the Cornhuskers are ranked 16th and a win by the Bruins — unranked in 78 weeks — could again earn UCLA some attention.

Veterans from both 1972 teams will be at the Rose Bowl. UCLA players are having a reunion dinner Friday and will be at the game. Rodgers will be there as well, posing for photos with his Heisman Trophy at a Nebraska tailgate function.

“They won’t get us this time,” Rodgers predicted. “We have to win. There are no laurels for us to rest on this time.”

The 1972 game, in a couple of ways, was a harmonic convergence.

Nebraska had not lost since 1969, a streak that started with a victory over a Kansas team coached by Pepper Rodgers. In 1972, Rodgers was in his second year at UCLA. The Cornhuskers’ only blemish during that undefeated span was a 21-21 tie with USC in 1970, a game also played at the Coliseum.

The Cornhuskers were talent-packed, with Rodgers, the Heisman winner, and defensive lineman Rich Glover, who would win the Outland Trophy. The season before, Nebraska had defeated Oklahoma, 35-31, in what was dubbed the “Game of the Century,” then beat Alabama in the Orange Bowl.

“A few months later, we’re back playing football and we weren’t done celebrating yet,” Rodgers said. “We took UCLA lightly.”

What national power wouldn’t have? The Bruins had won eight games the previous two seasons combined.

There were other factors too.

Rodgers said internal strife played a part. Coach Bob Devaney had announced he was resigning at the end of the season. Tom Osborne, a Cornhuskers assistant, had been chosen as his replacement.

“There were other coaches upset that they didn’t get the job,” Rodgers said.

UCLA already had a new look.

The Bruins had switched to the wishbone, run by Harmon, a transfer from Los Angeles Pierce College. Running backs McAlister and Kermit Johnson, known as “the Blair Pair” from their days starring at Pasadena Blair High, were together for the first time since they played on UCLA’s freshman team. McAlister had sat out the previous season because of irregularities on his entrance test.

UCLA offensive lineman Bruce Walton, the brother of Bill Walton, said Nebraska “expected us to mail it in. That didn’t happen.”

McAlister broke off a long run on the first play and finished with 90 yards rushing. Harmon’s first pass was a 46-yard touchdown to Brad Lyman for a 10-0 UCLA lead. Harmon also ran for 71 yards, including a touchdown that gave UCLA a 17-10 lead.

Rodgers had a 50-yard punt return to set up a field goal but finished with a modest 43 yards rushing and 63 yards receiving. UCLA forced five turnovers.

One play stood out to Harmon. He was tackled by Nebraska defensive back Mark Heydorff, a friend who had played at Glendale College.

“I remember him kneeling on my chest and saying, ‘Where’s your surfboard, California boy,’ ” Harmon said. “I looked at him and said, ‘Aren’t you from Glendale?’ ”

But the Bruins gave even better than they took.

“In so many ways that is what I came to UCLA to do,” said Harmon, whose father, Tom, a Heisman Trophy player at Michigan in 1940, was a television announcer working the game. “You’re 19, you want to be in the tunnel with 90,000 people in the stands, running onto the field with your teammates. When I was a kid running stats at games for my dad, that’s what I dreamed about.”

Harmon, after the postgame chaos, went to take a shower and found his father leaning against the wall.

“Dad was always careful to stay outside the box,” Harmon said. “He never even called me by my name during broadcasts. I was ‘the quarterback.’ ”

But that night, Harmon said, “he looked at me and said, ‘Great game.’ I started crying. He started crying. We reached out and hugged each other.”

Nebraska finished 9-2-1 and ranked fourth after clobbering Notre Dame in the Orange Bowl.

But UCLA, McAlister said, “had started something. You could feel a difference that next week.”

The Bruins finished 8-3 that season, 9-2 the next.

Said McAlister: “That game changed the momentum of things at UCLA.”

twitter.com/cfosterlatimes

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.