1968: Hockey’s western migration set stage for success in L.A., Las Vegas

The National Hockey League hit the jackpot last season when it expanded into the least traditional market imaginable.

The speedy, spunky Vegas Golden Knights became the hottest show in a city that appreciates entertainment, getting off to a good start and proving their success wasn’t a mirage when they reached the Stanley Cup Final. The NHL’s 31st team was a huge hit, selling out home games and attracting so many fans to practices that fire marshals had to set admission limits.

And to think there were questions whether hockey would find a respectable audience when the league expanded beyond its Northeast base and doubled in size to 12 teams for the 1967-68 season.

That first major expansion included Los Angeles, giving the league a transcontinental presence. The Kings had a passionate fan base and endured some lean years, but their 1988 acquisition of Wayne Gretzky, the game’s greatest player, transformed the West Coast into a prime hockey destination.

Gretzky ignited a boom that led to the birth of the San Jose Sharks in 1991, the then-Mighty Ducks in Anaheim in 1993 and the migration of teams to the Sunbelt. The Cup found a second home in Southern California when the Ducks won in 2007 and the Kings triumphed in 2012 and 2014.

The Kings have a home sellout streak of 289 regular-season and playoff games. And both local teams support youth programs that send streams of players to top college programs and beyond.

None of that would have happened if the NHL had stayed within its cozy confines.

From 1942 into the mid-1960s, it was a clubby group of six; Chicago was the outpost from teams clustered in Montreal, Toronto, New York, Boston and Detroit. Proposals floated in the early 1950s to expand within Canada or to cities such as Cleveland and St. Louis were laughed off as preposterous and impractical for a train-travel league.

The move of the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants to California for the 1958 baseball season opened new possibilities for professional sports around the time television was becoming a big player. CBS had aired some regular-season NHL games in 1956-57, but the league’s narrow reach limited its potential.

Pulitzer Prize-winning Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray, writing in 1962, decried the reluctance of NHL President Clarence Campbell to add a team in Los Angeles even though the minor-league Blades had solid support: “The ‘National’ Hockey League makes a mockery of its title by restricting its franchises to six teams, waging a kind of private little tournament of 70 games just to eliminate two teams, whereupon, like basketball, it starts all over again in the playoffs,” he wrote. “Any businessman will tell you that in a dynamic economy you either grow or perish. … Hockey just can’t sit there in the dark forever braiding buggy whips.”

Under threat of a challenge from the minor-level Western Hockey League and led by progressive owners Bill Jennings of the New York Rangers and David Molson of the Montreal Canadiens, the NHL announced in 1965 that it would accept expansion applications. More than a dozen were filed, including five from L.A.-based groups.

Canadian mogul Jack Kent Cooke won the L.A. team, which was placed in a division with Minnesota, Oakland, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and St. Louis. To Campbell, the league was “an international sports organization which is on the threshold of a new era,” even if it got there reluctantly.

“There seemed to be frustration among TV networks that they were more a regional hockey league, not a national hockey league, and owners knew if they were going to expand their revenue at all it couldn’t come from gate receipts because they were already selling out for the most part,” said Alan Bass, author of the book “The Great Expansion: The Ultimate Risk that Changed the NHL Forever,” published in 2011. “You couldn’t be halfway in Canada and just the northeastern United States, so that pushed the envelope a little bit and pushed the expansion forward,” Bass said.

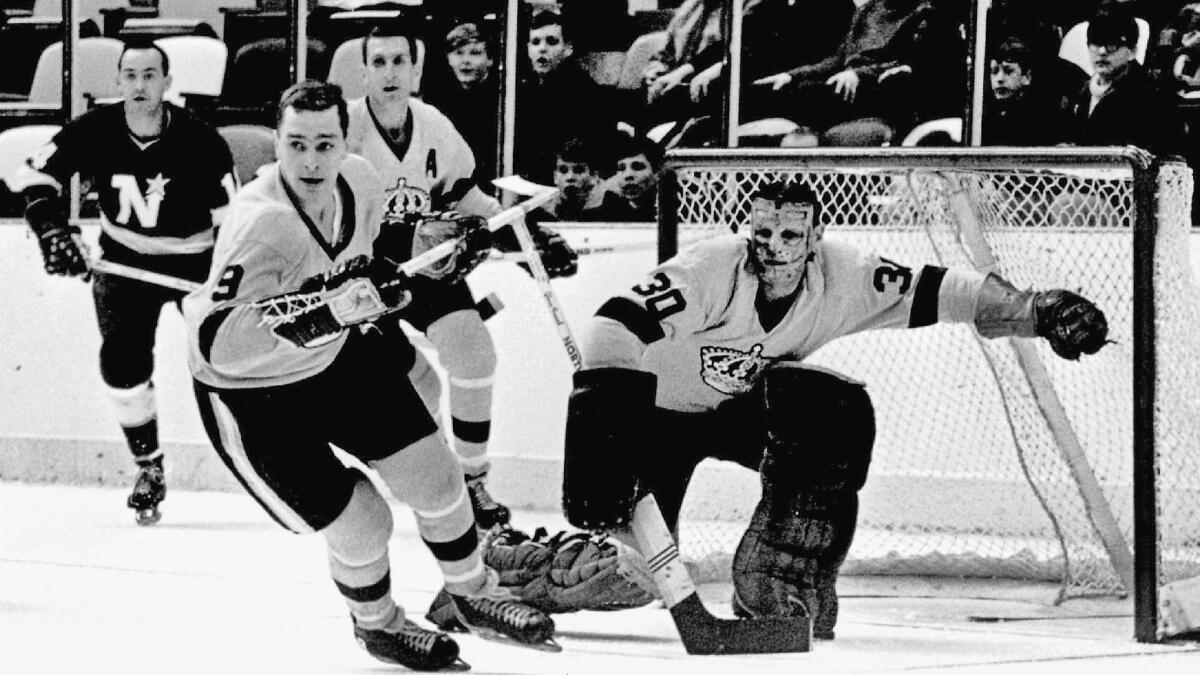

Some owners feared expansion would produce “clown clubs,” weak teams like baseball’s 1962 New York Mets. The Kings sought to ensure their competitiveness by smartly supplementing the talent they got in the expansion draft by purchasing control of the Springfield (Mass.) Indians of the American Hockey League.

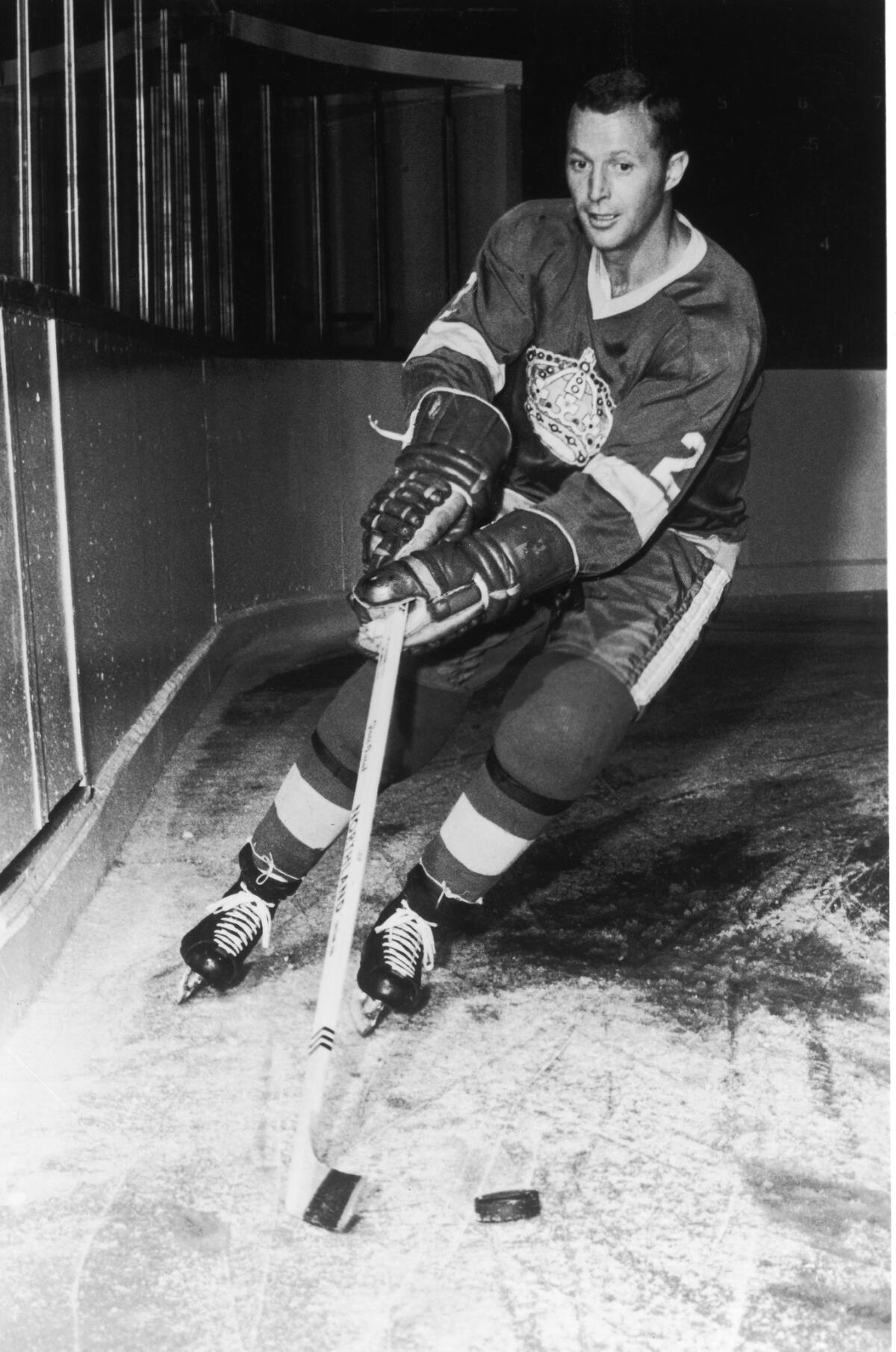

“That was the cat’s meow,” said Bob Wall, an expansion pick who became the Kings’ first captain. “… We got some pretty dangerous players that had been hidden there.”

Expansion granted a reprieve to hundreds of talented minor-leaguers. “Guys who were on the bubble or close to making it never got a shot until the expansion,” said Terry Crisp, a forward who was signed at 20 for $100 and made the Boston Bruins’ roster several times but failed to stick. “Then suddenly it changed and we were all given new life.

“At least when you went to training camp you knew you were going to get a shot,” added Crisp, who was picked up by the St. Louis Blues. “Whereas back in the six teams you didn’t have a crack unless you belonged to the old boys’ club or you were a young phenom coming in.”

Ted Irvine, plucked from Boston’s organization by the Kings, recalled entering a strange, new world at the team’s first training camp in Guelph, Canada.

“In those days, we were isolated. We were in western Canada and we didn’t know a lot about the Eastern teams and they didn’t know a lot about us,” he said. “So when we got to training camp we realized, wow, there are a lot of hockey players out there. In those days you’d read about it in the Hockey News. If your name was in there, you hoped they spelled it right and that’s how people knew you were playing.”

Wall had played 40 games for Detroit over three seasons before he read in a newspaper the Kings had claimed him in the expansion draft. “I thought, ‘This is up my alley.’ It was a great thrill to be drafted,” he said.

Putting the new teams in one division was smart because it guaranteed four would make the playoffs and bring fans to arenas. “Of the six teams that were added in ’67, some were exorbitantly successful,” Bass, the author, said. “Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and L.A. are some of the most valuable teams in the league now.”

Their success was possible because even though the NHL was new to those cities, hockey wasn’t. “Optimism was very, very high that it would work,” said Jiggs McDonald, who launched his Hall of Fame broadcasting career by becoming the first voice of the Kings. “All of the cities had had minor-league teams, successful operations, and L.A., of course, had had the Blades.”

Intent on establishing themselves, players didn’t look at the big picture. “We never even thought, could it work, wouldn’t it work. We were just so thankful to be out there and have them pay us some extra money,” said Irvine, who earned $11,500 his first year and remembers spending five weeks in training camp without money or a car. The Kings, he said, “gave us tickets to eat at the restaurants” but provided no transportation to get there.

“We got to L.A. and we were clueless,” he said. “Didn’t know about rental cars. Didn’t know about apartments. We didn’t know a lot of stuff. We just hung together and that’s what made it so exciting for the Los Angeles Kings, because being out in Los Angeles we were out in no man’s land, us and Oakland. We weren’t part of the NHL at all. Nobody knew anything about us.”

That disregard carried onto the ice: McDonald said he and other broadcasters believed the new teams were treated as second-class citizens by referees. “It was almost like a vacation trip when they came out west,” he said. “We felt we just didn’t have the respect of a lot of people, certainly of the officiating staff, though that changed over the years.”

Crisp, 75, has fond memories of the Blues’ early years. “Being a Canadian kid I thought this was a trip around the world,” he said. “I remember I used to hope I didn’t get cut or get hurt before we made our trip out to L.A and San Francisco.” Home games were a treat too. “It was like going to the ballet. By that I mean, the dress,” he said. “The women wore furs and jewels. The men wore tuxedos. We had suits on. Our owner put a five-star restaurant in the arena for the fans to come to. Man, oh, man. It’s changed a little bit since then, but it sure was neat when we were going through it.”

His memories aren’t soured by the Blues getting swept by the Canadiens in the Cup Final in each of their first two seasons and again by Boston in their third year. In 1968, each game of the Final was decided by one goal, twice in overtime. “I have a real sense of pride. I was part of a team that was not only the first expansion team to get to the Finals but also put on a pretty damned good show,” Crisp said.

Although most players didn’t live year-round in their new cities, they were aware of the civil unrest that existed in the U.S. in the late 1960s. McDonald, told to register for the draft, recalled reporting to an office not far from the Forum. Since he was older than most prospective draftees, three young men asked why he was there and where he was from. Canada, he told them.

Their reply, he said, was an incredulous, “‘We’re going there and you’re coming here?’” In a more serious vein, the start of the Kings’ first playoff series in April 1968 was delayed after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. “There was concern among a lot of players about just what was going on in the country and whether it would affect them,” McDonald said.

Irvine was at the Forum when a riot broke out after a bantamweight fight on Dec. 6, 1968. “I remember Doug Robinson and I walked out a door and a two-by-four came through the glass door beside us,” Irvine said. “The unrest in the neighborhoods, and it was different ethnic groups, that really caught us off guard. We didn’t see a lot of that in Canada at that time. You could feel the racial tension of people, and the fear, and that kind of threw us off quite a bit, being in L.A.”

Four of the NHL’s 1967 additions survived; Minnesota moved to Dallas and California/Oakland moved to Cleveland. The NHL soon went on an expansion spree, adding Buffalo and Vancouver in 1970 and a second team in New York (the Islanders) and its first team in the south (Atlanta) in 1972. In 1979, it absorbed four teams from the rival World Hockey Assn.

The Golden Knights this season became the first expansion team to reach the Final in their first season since Crisp’s 1968 Blues, and he enjoyed following their progress. “I love it,” he said.

Wall envied the talent available to Vegas in the expansion draft. “They were able to take one player from each of the other [30] teams, so they all had NHL experience,” he said. “They weren’t starting on the ground floor,” as the Kings had.

Wall, 75, was invited to a Kings game last season as part of the team’s 50th-anniversary celebration. He was impressed with the Staples Center locker room and the jersey the team made for him. He took pride in his part starting it all.

“I like to say it was like trying to plant a tree in Los Angeles, and hopefully it blossoms into something pretty and picturesque,” he said. “We were a seed that was planted in Los Angeles and we just wanted to excel. I don’t regret a minute of it.”

Twitter: @helenenothelen

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.