Steve Nash didn’t look like a Hall of Famer when he got to college

Steve Nash’s career almost ended before he could get past half court.

The story has been told before. In 1992, his freshman season at Santa Clara, returning guard John Woolery tortured Nash in the backcourt, forcing him into turnover after turnover before the team could even set up the offense.

With everyone on the floor staring at the skinny point guard from Vancouver Island, coach Dick Davey escorted Nash down the court to the top of the opposing key, where the play was supposed to begin.

“Think you can do it from here?” he asked.

It was a low point — an embarrassing one that almost pushed Nash to leave Santa Clara.

“It was bad. He was upset. You could see it,” his friend and teammate, Phil Von Buchwaldt, remembered. “And most people would’ve quit. But he had that belief.”

Von Buchwaldt has the proof.

One month into that freshman year, the two men sat in study hall in the campus library when Nash declared he’d someday play in the NBA.

“I remember just thinking, ‘What an idiot,’ ” Von Buchwaldt said. “Sure. Whatever. I’m going to take advantage of this guy. ‘Steve, if you really believe that, why don’t you put it in writing for me.’

“And he said, ‘Hell, yeah, I will.’ ”

Von Buchwaldt grabbed a blank note card and wrote. “If by the end of my senior year I’m not drafted and don’t dribble the ball down an NBA floor, I will pay Phil Von Buchwaldt $100.”

Within three years, Von Buchwaldt, now a banker in Spokane, Wash., knew that deposit was never going to be made.

“He was fully convinced he was going to make the NBA,” Von Buchwaldt said.

He did more than that.

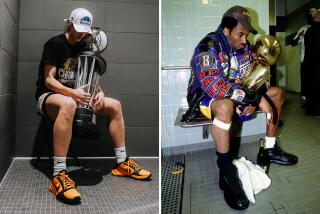

Nash will be one of 13 people inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame on Friday, co-headlining a class that includes Grant Hill, Jason Kidd and Ray Allen.

A two-time MVP, an eight-time All-Star and a seven-time All-NBA selection, Nash didn’t just win the bet in an 18-year career between Phoenix, Dallas and Los Angeles, where he ended his career with the Lakers, he earned a place in history.

“He was a tough-minded son of a gun,” Davey said. “He wanted to be as good as he could possibly be. He was so deranged about the game — had a great feel and a love for the game.”

Davey said he knew he might be onto something the first time he watched Nash play during a tournament in Canada. Within 30 seconds of pregame warmups — warmups! – Davey had a feeling about Nash.

“I thought there was a darn good chance this guy was going to be something special. How special? I didn’t know,” Davey said. “It was just his flair for the game. I was pretty much convinced he was going to be a good one, but I didn’t expect what would happen.”

While Nash played that game — and he played well — Davey scanned the stands for signs of other coaches, looking for familiar faces or golf shirts with logos. He didn’t see anyone else in on his secret.

Soon, he’d learn more.

“A three-hour practice wasn’t enough for him,” Davey said. “He’d come back at night and shoot. It got to the point where he’d bring five or six guys with him. It wasn’t just him getting better, it was the entire team getting better because of him.”

Nash making his teammates better — it’s the mantra for point guards of his ilk — continued in the NBA, where he and Dirk Nowitzki became stars together.

Nash returned to Phoenix to run the fast-paced Suns offense, putting together some of the best shooting stats in league history. In four of his first six years in Phoenix, Nash shot better than 50% from the field, 40% from three-point range and 90% from the free-throw line — standards of complete excellence.

Nash helped change conventions about basketball.

He wore his traditional-minded coach down, earning the green light to launch deep shots in transition and to fire one-handed passes — a pet peeve of Davey’s.

“He said, ‘Let me explain something to you: It’s three-tenths of a second faster to throw it with one hand than it is to pick it up and throw it with two. And that gives the shooter three-tenths of a second more to shoot,’ ” Nash told Davey years later. “ ‘OK, Steve, I get it now. You win.’ ”

His rise in the NBA coincided with the game becoming more open and, as he aged, he became an example of modern fitness.

“All that sports science stuff people would talk about? Nash had been on that for over a decade,” said Jared Dudley, who played with Nash in Phoenix. “He was doing the one-legged squats on the BOSU ball, the band work, at a time this was unimaginable. When people say he was deranged about basketball, I say he was deranged about his body, from [what he did for] his back to what he put in his body. He was so deranged, he wouldn’t drink water from plastic bottles. It had to be from glass because the water was more purified.”

Nash did acupuncture, had cryotherapy. He obsessed about his diet, yelling at teammates who chomped on pizza.

All of it is now commonplace in modern training programs.

“People will look back on it, this whole new era,” Dudley said, “and in a lot of ways, it started with Nash.”

It almost didn’t happen — a few more John Woolery steals might’ve cracked him. Instead, it just made him more committed to the work, to the process of proving doubters like his buddy Von Buchwaldt wrong.

“He just never got tired of doing that,” Von Buchwaldt said.

Twitter: @DanWoikeSports

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.