Fun and philanthropy in Kenya

Patrick Nyaleta was a cow herder by the time he was 6. Like many rural Kenyans, his father measured his wealth in cattle and needed his children to tend them.

One day, Patrick threw a rock at a wayward cow, killing it — the Kenyan equivalent of wrecking your father’s roadster. His father beat the 8-year-old boy, yelling, “You will never again touch my cows!” Patrick was packed off to school in disgrace.

“I was a skinny boy with no shoes, and I couldn’t read or write,” says Patrick, who now speaks German, Italian, English, Kiswahili and several tribal languages. “But for years I had watched other kids walk past carrying books while I spent all day alone talking to cows. Oooh-wee, I thank that dead cow today.”

Patrick today is a safari director for Nairobi- and New York-based Micato Safaris. He accompanies guests, including my 11-year-old daughter, Indigo, and me, on their East African adventures. As a guide, Patrick also provided instant insight into Kenya’s people, politics, history and humor.

Despite the U.S. State Department travel warning on Kenya, my research and reading indicated Kenya was safe for a trip that was part indulgent fun, part philanthropy. We would spend 10 days on safari and two more visiting orphanages and a community center in Nairobi’s Mukuru slum. For the safari part of the trip, the tour company suggested activities varied enough to keep a child and her mom fully engaged.

Sabuk, Samburu

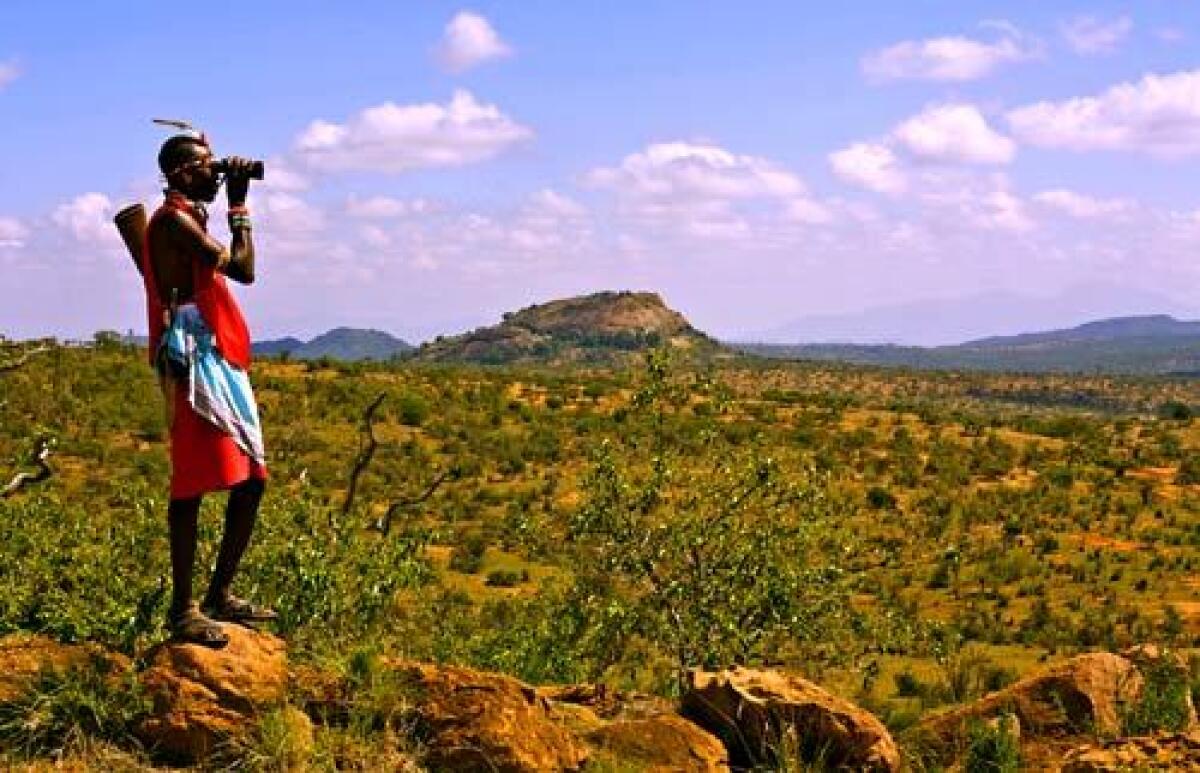

I’d always hankered to go to northern Kenya’s Samburu country, an area that’s remote and thus less visited by tourists. The Samburu people dress traditionally and live in villages, as they have for centuries, and unlike some other places in Kenya, none of this is done for tourists.

Our destination was Sabuk, a family-friendly lodge on a private game reserve. It has eight open-air rooms built around tree trunks and boulders and overlooks the dramatic Ewaso Nyiro River valley.

After arriving, we took a sunset walk, something I had requested we do often. Many of Kenya’s national parks and reserves frown at walking safaris because of wild animals, but private reserves allow it by sending you out with askaris, or native armed guides.

Ngasakwe “Gus” Kipise, Sabuk’s Samburu guide, introduced himself in hesitant English. Samburu people are like the Masai to whom they are related; their language, customs and diet are similar, and both are tall and thin with fine, narrow features. Gus wore a traditional shuka, or cloth tied diagonally at the shoulder, abeaded headdress, necklaces and sandals made from tire treads. He also carried a heavy stick and rifle and exuded such competence that we felt at ease.

The Samburu area is light on the exotic animals such as lions, but there are plenty of elephant and buffalo, the most dangerous animals in Africa, some would say.

One morning, we climbed on Sabuk’s trained camels for a safari with a twist. Brought from Somalia and used as pack animals, camels do well in Kenya’s hot, dry climate. Gus refused to ride. “Gus’ legs better,” he said. For Samburu, like Masai, walking is as natural as sleeping. They can cover hundreds of miles in a few days.

Patrick, who is no longer the skinny kid he once was, sat astride one ornery beast dutifully answering my questions about the tumult that is Kenyan politics and the relationship among Kenya’s 47 tribes.

In 2007, post-election riots broke out in Nairobi, morphing into several months of inter-tribal warfare. The city ground to a halt. Tourism dried up. It wasn’t until 2009 that visitors returned in numbers. Kenya is peaceful again, and it seems more organized and Nairobi safer than during my previous visits in the late ‘90s.

Having lived through several political upheavals, Patrick was matter of fact in his explanations of tribal frictions. He did, however, look tortured on a camel. Having come here to learn more about the Samburu tribe, I was eager for a village visit, which happened one orange-lit afternoon. Lobarishereki, the closest village, was a 40-minute drive from Sabuk, and its school was the only one within a 50-mile radius. It had three cinderblock classrooms for 250 children. Outside, a group of scrawny boys played soccer on a dusty playground with a ball made from plastic bags tied with string.

The Samburu have suffered from three years of drought, and the children, while thin, were in uniform, no matter how torn or ill fitting.

“Some of these children walk nine miles each way to come to school,” said Maina Kiboi, the headmaster. “But they feel lucky to be here.”

Two 18-year-old boys sat like Goliaths among the third-graders, finally coming to school because their cows had died of starvation.

Down the road at the boma, or village, shave-headed Samburu women, who wore wide beaded necklaces and headdresses, swarmed out to greet us. Pushing aside baby goats, they invited us into their dark, smoke-filled huts, which have neither electricity nor running water.

Outside the village, moran, young warrior men, gathered to dance. This involved impressive displays of jumping to great heights from one spot. The warriors wore their hair either in long braids or decorated with ocher, feathers, metal objects, buttons and fabric roses. In this society, it’s the boys who primp and fall prey to vanity while the teens girls help run the household.

Having danced with the women and narrowly escaped the ownership of a baby goat, we said farewell. It was, as all village visits in Africa have been for me, the happiest of human encounters.

Elsa’s Kopje, Meru National Park

Elsa’s Kopje is a lodge built on the former site of George and Joy Adamson’s camp, the setting for the 1966 film “Born Free.” Far from the Adamsons’ rough canvas tent camp, Elsa’s Kopje is now an elegant retreat perched atop a hill with a 360-degree view.

The 340-square-mile Meru park, recognized for its lions and a rhino sanctuary, remains one of the wildest and least visited of Kenya’s parks. Unlike the flaxen plains of the south, the landscape here was green and lush, dotted with doum palms — a tall, graceful, bifurcated tree. There were lions everywhere, hunting, eating, playing, mating and observing us closely.

It was in Meru that Elsa became the first lion to be released successfully into the wild. The release went well, but life for the Adamsons was full of tragedy. They divorced, George’s brother was killed by one of the “pet” lions, and later Joy and George were slain, she by a former employee and he by poachers.

None of that specter hung over our house on the kopje (hill). It was so lovely, with such expansive views of the plains below and a family of rock hyrax (imagine a corpulent guinea pig) living in the rocks outside that we skipped a couple of game drives just to swim in the pool and observe the droll hyrax.

Basecamp, Masai Mara

In these days of blatant greenwashing, it’s refreshing to stay at a place that really is eco — so eco, in fact, you wish they’d consider using more chemicals in the composting loo in your tent.

Set outside the southern end of the Masai Mara Game Reserve, Basecamp has 12 basic safari tent-rooms. The power is solar, and everything that can be recycled or composted is. The camp also employs the local Masai and has a women’s cooperative making stylish beaded accessories that sell globally. It’s not the most luxurious place on the Mara, but it feels good to stay here.

The Masai Mara, on the southern border with Tanzania, is the most visited park in Kenya, probably because it has plentiful game and the archetypal “Lion King” golden grass and flat-topped tree landscape.

One night, Patrick shepherded us into our vehicle and would not tell us where we were going. It was dark, and the bush looked empty and daunting. Eventually, we rounded a corner and saw a campfire in a clearing, flanked by the shadowy figures of Masai askaris leaning on spears. Off to one side was a dining table illuminated by hurricane lamps. Beneath a tree a chef prepared dinner on a camp stove. I laughed, thinking perhaps I knew how charmed author Karen Blixen (“Out of Africa”) must have been when Denys Finch Hatton brought her to the Mara.

Indigo and I sat at the table with Patrick and Amos Ole Tininah, a young Masai and the head naturalist at Basecamp. When I first started coming to East Africa 16 years ago, I rarely had the chance to dine with Africans so I had missed hearing the stories about what it was like to grow up in Africa.

On our final morning, we woke at 4:30 to take a dawn hot-air balloon ride. As the balloon rose, the new sun cast the world purple, then yellow. The air was still and silent but for our blasts of hot air. Below us wildebeest, antelope, kudu and giraffe fled from our shadow, a lion pride looked up annoyed, jackals disappeared into holes and outraged ostriches ran in circles flapping their wings.

Later that day we were back in Nairobi eating lunch at the Karen Blixen Coffee Garden Restaurant, a historic house near her farm. We sat in the garden under 100-year-old trees, and I peppered Patrick with final questions.

“So what does your father think of you now?” I asked.

He paused and smiled, “Well, I suppose he’s proud. But he still has cows and still needs help herding them. That is the old Kenya, and I am the new.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.