Coronavirus means social distancing. For flight attendants, it’s suddenly easier

As COVID-19 continues to spread around the world and in the United States, the airline industry is taking a major financial hit. Airlines have reduced flights dramatically because of decreased passenger demand.

Delta has announced system-wide flight reductions of 70%. American will cut domestic and international flights by 20% and 75%, respectively. United is slashing international flying by 85%.

The International Air Transport Assn. predicts airlines could lose more than $131 billion in sales if the coronavirus is not contained soon.

In an attempt to stave off furloughs, carriers have asked employees to accept leaves of absence and early-out retirement packages.

I’m one of those employees. I’m faced with grim choices as a flight attendant working for one of the world’s largest carriers.

My airline offered an early-out retirement package that includes two years of medical coverage, free flights and no monetary payout. Like many in my position, I can neither afford to retire nor relinquish my precious medical benefits in 2022.

My airline also offered leaves of absence for one month to one year. Again, these options provide free employee travel but zero income.

Then there’s the option to fly.

Because flight schedules have been severely reduced, few opportunities exist for flight attendants willing to work. And social distancing — a term we’ve all become familiar with — is nearly impossible to accomplish on an airplane.

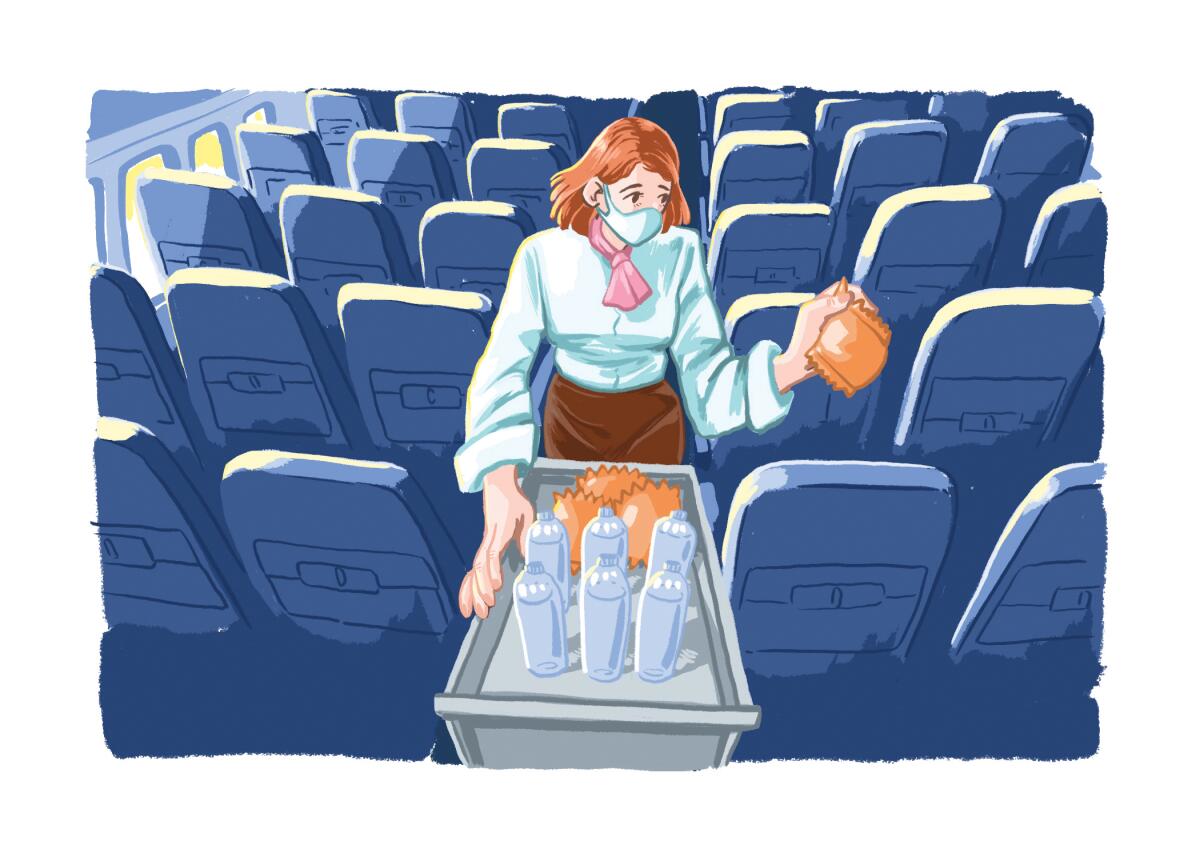

Flight attendants work in extremely tight spaces for hours at a time. We squeeze past passengers’ shoulders while pushing a 200-pound beverage cart up a narrow aisle. We trip over protruding feet. We reach over bodies to serve food and beverages. We stand at arm’s length before a captive audience, performing mandatory safety demonstrations.

In best-case scenarios, we can’t put 6 feet (the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention‘s recommended distance) between our customers and ourselves to prevent the spread of , the virus. In worst-case scenarios, I wonder if some of us would choose self-preservation over passenger care.

Consider, for example, a serious in-flight medical emergency. In the unlikely event a passenger loses consciousness and stops breathing, flight attendants are trained to retrieve a Laerdal pocket mask. The mask is placed over the victim’s nose and mouth. One attendant blows two breaths through the mask and then a second crew member begins chest compressions. The mask allows a user to blow while providing a barrier between the victim’s mouth and our own.

Given the times, how many flight attendants would hesitate to treat an ill passenger because we have limited protective gear at our disposal?

By now everyone understands that the coronavirus is transmitted primarily by human-to-human contact. Microscopic droplets passed by sneezing and coughing are believed to be the most potent methods of transmission, according to the CDC.

Flight attendants are not healthcare professionals. We’re trained to treat symptoms, not diagnose illness. Treating every symptom requires some form of attendant-to-victim contact.

Although my airline issues latex gloves for protection, we don’t have access to the N-95 respirator masks used by some healthcare professionals.

So when a passenger collapses and a flight attendant performs mouth-to-mouth resuscitation—even while using a Laerdal pocket mask — or when turbulence makes someone sick and a flight attendant cleans up the mess, the health of that flight attendant may be compromised.

Restaurants have discontinued table service to help prevent the spread of COVID-19. Schools, bars, houses of worship, gyms, concert halls — all sorts of gathering places have shut their doors due to government decrees. But airplanes seem exempt from restrictions.

Because of this reality, some flight attendants (and most passengers) are unsure about whether to fly.

Thirty-five years with one airline likely grants me enough seniority to protect me from impending layoffs. I’m single with no children and no credit card debt. I drive a 2008 Honda Civic paid off eons ago. Thanks to years of flying “high time” (overtime) and living well below my means, I have an emergency fund that can help me steer through bumpy skies.

Many of my colleagues aren’t so fortunate.

Given my blessed circumstances, at least one roster spot will be available for someone who absolutely needs to work. I applied for and was granted a temporary leave of absence.

Of course, flight attendants aren’t the only work group affected by flight reductions. Pilots, flight crew instructors, mechanics, customer service agents, dispatchers — virtually every airline department has staff that has been asked to take a leave or put in for early retirement.

Reservation agents are perhaps the only work group immune to job cuts because of the unprecedented volume of customer calls.

A few nights ago, while preparing to write this column, I received a text message from a flight attendant friend. It was near midnight. She was moving 500 mph at 30,000 feet working a red-eye from Philadelphia to Los Angeles and had just finished the in-flight beverage service. It was strange she had logged on to in-flight Wi-Fi when she should have been attending passengers.

Curious, I texted, “How many passengers on ur flight?” She was working an Airbus 321 configured with 16 seats in first class and 171 in the main cabin. On a typical day, most of the 187 seats are occupied.

“We got only seven passengers,” she replied. “Seven. And four of them are airline employees.”

On this flight — as is the case on a growing number of flights in the age of COVID-19 — social distancing proved easy to achieve.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.