Lebanon defies its reputation for tolerance and cancels a concert

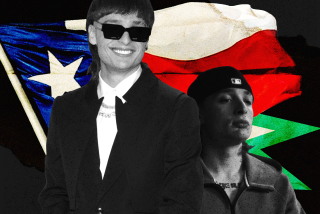

When the Lebanese indie rock band Mashrou’ Leila wanted to go on tour in the Middle East, few were surprised to see the group banned from performing in Egypt or Jordan.

The band’s frontman is openly gay and its songs often feature taboo-laced lyrics dealing with gender and sexuality issues as well as social justice — all an affront to the conservative values in those countries.

The band expected little trouble, however, at home in Lebanon, which is often feted as relatively accepting of free expression compared with many of its neighbors.

Mashrou’ Leila was to perform on Aug. 9 at an annual summer festival held in the Lebanese coastal city of Byblos, a venue where it had appeared several times in the 11 years since it was formed.

But on Tuesday, after days of pressure by Christian groups and threats of violence against the band’s four members, the festival’s organizers canceled the concert and released a statement saying it was an “unprecedented step” that aimed to “prevent bloodshed and preserve security and stability.”

“We are sorry for what happened, and apologize to the audience,” it said.

The band later released its own statement, saying any offense its music had caused was unintentional and that it had been a victim of a disinformation campaign.

The cancellation quickly became, for many, emblematic of something larger: a fraying of freedoms in the country.

“This decision is a devastating blow for the right to freedom of expression in the country and exposes the Lebanese authorities’ abdication of their responsibility to ensure that the band was protected amid a mounting hate campaign,” Lynn Maalouf, Middle East research director for Amnesty International, said in a statement.

“This is the direct result of the government’s failure to take a strong stand against hatred and discrimination and to put in place the necessary measures to ensure the performance could go ahead.”

Lebanon’s track record of tolerance of different political and religious leanings stems in large part from a power-sharing agreement among the country’s 18 sects, which guarantees that no one person can completely dominate.

Political parties, nevertheless, regularly push their line through affiliated newspapers and TV channels, and run de-facto fiefdoms based on patronage in their areas. They have also pursued journalists or comedians, often under usually unenforced laws proscribing defamation of public officials and institutions or foreign leaders.

Lately there has been an increase in those kinds of crackdowns — none more prominent than the cancellation of the Mashrou’ Leila concert.

In recent days, there had been a steadily escalating chorus of church groups and political leaders railing against the group for allegedly insulting religion.

The Maronite Catholic Eparchy of Byblos said in a statement last week that the content of the band’s songs offends “religious and human values and attacks Christian sanctities.”

The same day, a lawyer filed a court complaint against the group for “spreading and promoting homosexuality.”

Online, matters escalated.

One group, which calls itself Parti Democrate Chretien, posted images of armor-donning Crusaders and threatened to violently stop the concert.

“Our battle on August 9 is one of life and death,” read the caption under the photograph.

Christian fundamentalists accused the band of being Zionist, Masonic or devil worshipers.

Newspapers in Lebanon highlighted one online post that claimed the band’s name, which translates to “Night Project,” was in reality a reference to Lilith, Adam’s first wife, who in the Talmud was said to be a sexually wanton seducer of men and child killer.

Later, lawmakers from the country’s largest Christian-dominated parties joined in, threatening to stop the concert by force if necessary. The government, instead of heeding calls to protect the band, subjected its members to hours of interrogation by state security officers over allegations of insulting religion and inciting sectarian strife.

After being released without charge, the band members removed content on their Facebook page that was deemed offensive.

There were also impassioned calls for solidarity with the band, which is scheduled to play at the Regent Theater in Los Angeles on Oct. 3. On Monday, supporters filled a public square in Beirut’s glitzy business district. They swayed to a loudspeaker blaring the group’s music above cars honking nearby, and interrupted the dancing with chants cheering for “freedom” and “Leila.”

Reaction to Tuesday’s announcement was swift.

“Sadly, what happened today is that sectarian powers, who had normally operated behind the scenes in telling state security or censorship groups what to do, are now doing it openly,” said Nayla Geagea, a lawyer and a member of Beirut Madinati, an independent political movement made up of civil society organizations.

“Today we put all state institutions to the side, and a sectarian power showed that it was the de-facto authority. This is the disaster, not how the concert was canceled.”

Ayman Mhanna, director of Beirut-based media watchdog group SKeyes, said the cancellation set a dangerous precedent.

“The fact that the band was questioned by state security is appalling,” he said. “Yet those who expressed explicit threats online are roaming free despite very clear violations of our laws.”

“Now every time a bunch of armed men, political parties or religious groups are unhappy with an idea, whether it’s coming from academics or artists, they know they can resort to threats because state authorities are not doing anything to protect … the values we all thought were natural in a country like Lebanon.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.