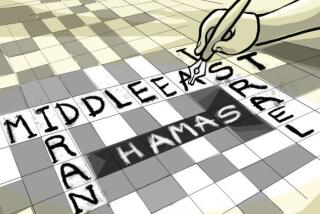

Game of Shows: In the Middle East, TV programs launched as weapons of war

In the shadow war for regional influence between Turkey and a Saudi-led coalition, there have been many proxy battlefields across the Middle East and beyond. Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Egypt are arrayed against a Muslim Brotherhood-inspired alliance that includes Turkey and Qatar.

The competition, which has on occasion overshadowed that with Saudi Arabia’s main nemesis, Iran, has seen both sides arm opposing belligerents in Libya, vie for control of strategic ports checkering the Horn of Africa coast and squabble over each other’s machinations in the blockade of Qatar.

Now they’re jousting in an arena where Turkey has hitherto had undisputed dominance: television series. Last month, the Saudi-owned MBC network, the Middle East’s most-watched broadcaster, debuted “Kingdoms of Fire,” a 14-episode drama depicting the 16th century defeat of the Mamluk Sultanate — which encompassed the lands of modern-day Egypt and stretched all the way east into parts of Saudi Arabia — and the expansion of Ottoman rule into Arab lands. The aim, the show’s producer says, is to focus on the history of the Ottoman Empire not as the zenith of Muslim unity but as a dark time for the Arabs; and how it echoes today in Turkey’s current role in the region through the neo-Ottoman policies of its president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

“The Arab world entered into darkness because of the Ottoman invasion,” said Emirati producer Yasser Hareb in a phone interview. “After all of the criminality actions of the Ottomans in the area, some people present them as the protectors of religion and Islam.”

“And now, these neo-Ottomans say they will restore grandeur to the Islamic nation. We had to respond to this.”

“Kingdoms of Fire” focuses on Tuman Bay II, who led the Mamluks in Egypt and fought a vigorous if ultimately losing campaign against the Ottoman sultan, Selim the Grim, in 1517. The defeat ushered in the era of Ottoman leadership over the Muslim world, a period that Turkish history often depicts as a moment of glorious pan-Islamic unity, but which “Kingdoms of Fire,” in its promotional materials, says was a time of “bloody rule” and a “curse.”

“To every Arab: The unjust Ottoman enemy wants to invade our lands,” says Tuman Bay as he rallies his troops in one episode, adding that whenever “those barbaric, butchering Ottomans” enter an area, they “pillage its resources, kill its scholar and enslave its people.”

“I promise Allah before you that the Ottoman enemy will not rule this area except over my dead body.”

It’s an argument the show spares no expense in making: The production, which took over a year and a half and cost about $40 million, far outstrips spending on most other Arab TV dramas and features epic battle scenes reminiscent in their scale and scope to “Game of Thrones.”

At its helm is British director Peter Webber, known for films such as “The Girl With the Pearl Earring” and “Hannibal Rising,” and the cast features heavyweight Egyptian and Syrian film stars.

That sort of firepower is essential as the series competes against a bevy of Turkish dramas that all but invaded the Arab world after 2007, when telenovela “Gumus” (“Silver” in Turkish; it was renamed “Noor” for Arabic audiences) was dubbed and broadcast in Saudi Arabia and beyond on MBC. It was a gargantuan hit; its finale had 92 million viewers across the region glued to the screen, while its actors became instant stars throughout the region. (One actor, a blond, blue-eyed hunk who went by the name of Kivanc Tatlitug, reportedly caused more than a few divorces — sought by husbands angry when their wives openly swooned at his good looks.)

“Gumus” was the start of a global obsession with Turkish epics, known as dizi, which have vaulted Turkey into the second largest worldwide distributor of television shows after the U.S. Now, dizi are broadcast in more than 140 countries and have reaped for their production companies revenue to the tune of $350 million a year, according to 2017 figures from the Turkish Culture and Tourism Ministry.

Adding to the bonanza, millions of tourists come to Istanbul, Turkey, every year eager to retrace the steps of the characters they’ve seen on various shows.

Such series have become a form of soft power for Turkey and Erdogan, its pugnacious president who espouses a form of Muslim nationalism while styling himself, critics say, as the model of a modern Ottoman ruler and caliph for Muslims worldwide. Two dizi in particular — “Resurrection: Ertugrul,” which depicts the conquests of Ertugrul Gazi, the father of the Ottoman Empire’s founder, and “The Last Emperor,” a show about Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II — push a view of Ottoman rule as a boon to both Arabs and Turks, and that the Ottoman Empire’s demise was the start of the region’s turmoil.

“Until the lions start writing their own stories, their hunters will always be the heroes,” said Erdogan of “The Last Emperor” in a 2016 speech.

Erdogan’s vision for the Middle East, along with his support for the Muslim Brotherhood, the Sunni Islamist political movement with adherents across the region, has put him in competition with Sunni-dominated Saudi Arabia and its allies. Like the conflict with Shiite-led Iran, which only months ago appeared to bring the region to the brink of war, their rivalry has involved blood, oil and often clumsy battle by proxy.

The Sunni powers crossed swords in 2013, when Saudi Arabia backed a military-led coup in Egypt that toppled the Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated President Mohamed Morsi, an ally of Turkey whose loss still rankles Erdogan. In Libya, Turkey supports the United Nations-supported Government of National Accord, a body that its opponents insist is under the sway of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Matters came to a head when Erdogan assisted Qatar, a Muslim Brotherhood ally, against a Saudi-led blockade. Last year, MBC pulled the plug on six Turkish television dramas, placing an unofficial moratorium on broadcasting dizi on all its channels, a decision that producer Hareb said was long overdue.

“We have a problem with people being passive while others invade us with their culture and films and songs,” he said.

“Kingdoms of Fire” scriptwriter Mohammad Abdul Malek added that, unlike “Resurrection: Ertugrul,” a production of Turkish state TV, his series, produced by an Emirati company and Saudi-financed, has been meticulously researched.

“I took six months to write the script, and worked with a fact-checker to ensure accuracy in our story,” he said in a phone interview.

Regardless of how close it hews to the truth, “Kingdoms of Fire” got a lashing from Turkish and other pro-Erdogan commentators, who say the show aims to foment divisions between Muslims.

“What is the aim of this series? It’s to attack the Ottoman state, and if we compare it with Turkish series, there are no series targeting Arab countries so far,” said Yasin Aktay, an advisor to Erdogan, adding it was an ill-intentioned show that abused “historical data for an ideological or political reason.”

“This is, of course, not the reality of the past, it is just the image of some contemporary guys.”

Hareb remains unapologetic.

“Erdogan and his supporters say that Arabs yearn for the return of the Ottoman Empire,” he said. “But what did we get from them during their rule? Nothing.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.