The board of directors of Nicaragua’s oldest newspaper sat down in January to discuss the future. It looked bleak.

Like many print publications in the digital age, La Prensa had been struggling for years amid declining advertising revenue. A recent economic recession had made things worse.

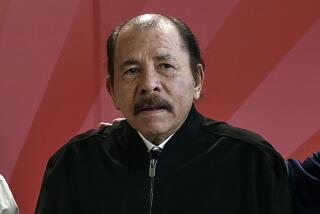

But the Managua-based newspaper faced another, more immediate challenge. For more than a year, President Daniel Ortega had barred La Prensa from accessing two of its most essential ingredients: newsprint and ink.

The government did not explain why it was holding up roughly half a million dollars of supplies in customs, but its actions were widely viewed as retaliation for La Prensa’s coverage of anti-government protests that erupted in 2018 and were brutally repressed by police.

Since then, the government had waged war against the Nicaraguan press, harassing, arresting and sometimes torturing journalists.

The blockade on newsprint and ink had already forced the country’s only other daily newspaper, El Nuevo Diario, to close its doors. Now La Prensa faced the same fate.

“They are slowly strangling us,” its editor in chief, Eduardo Enríquez, told his colleagues gathered around a long table that day.

“It is a catastrophe,” agreed editorial page editor Luis Sánchez Sancho.

La Prensa had already eliminated several sections, reducing its page count from 36 to eight, and had stopped distributing newspapers in all but four of Nicaragua’s 17 districts. The newspaper and its companion publication, a tabloid called Hoy, were being printed on thick bond paper, which was available only in small quantities domestically and at a much higher cost than newsprint.

Funds were so tight that Enríquez had been forced to lay off 75 of his 100 employees. Those who remained peered glumly around the mostly empty newsroom, wondering if they would be next to go.

La Prensa had protested the blockade. A year earlier it had published a front page that was blank except for a provocative question: “Can you imagine living without information?”

Now, the directors agreed, it was time for another dramatic plea for help.

So on Jan. 27 the newspaper ran an editorial with a headline that read: “Dictatorship strangles La Prensa!”

An online version of the article captured widespread attention globally with its stark warning: If La Prensa and Hoy were forced to stop publishing, Nicaragua would be left without a single printed newspaper.

“Don’t let La Prensa die,” it implored.

Ortega has long been hostile to the independent press, dating to his days as a Sandinista guerrilla fighting the right-wing dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza. Even back in the 1970s, Ortega distrusted the media and preferred speaking to propaganda outlets loyal to the revolution.

His relationship with La Prensa was especially fraught.

The newspaper, run for nine decades by the Chamorro family, has been a thorn in the side of governments across the ideological spectrum, and its history has been closely entwined with Nicaragua’s.

It was the 1978 assassination of La Prensa Publisher Pedro Joaquin Chamorro, a vocal critic of the dictatorship, that touched off the civic uprising that eventually ousted Somoza and brought Ortega and his Sandinista party to power.

But when the newspaper began to criticize Ortega, he responded by censoring it. During the height of fighting between the ruling Sandinista National Liberation Front and U.S.-backed Nicaraguan Contra rebels, Ortega’s government ordered the newspaper closed for more than a year, accusing it of “supporting U.S. aggression.”

Ortega eventually allowed it to reopen.

But a few years later, in 1988, he blocked the import of La Prensa’s newsprint, forcing the newspaper to stop publishing for several days.

Those aggressions helped spur Chamorro’s widow, Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, to run against Ortega in the presidential election in 1990. She won and served until 1997. The Sandinistas were booted from power for 16 years.

When Ortega was reelected president in 2006, he was more determined than ever to control the media. He announced a new communication strategy that called for limited engagement with journalists. “We will discuss the themes that we wish to discuss,” the document outlining the strategy explained. “We will define the boundaries of the discussion.”

Ortega was making life harder for journalists in other ways.

Longtime La Prensa reporter Emiliano Chamorro Mendieta, who is not related to Pedro Chamorro, said that once, after he wrote about a Catholic bishop who had criticized the Ortegas, he was trailed by intelligence officers and his children were harassed at school. Death threats followed.

Things got worse when a wave of anti-Ortega protests broke out in the spring of 2018, and tens of thousands of people flooded the streets. Chamorro was there to cover them, and said police and pro-Ortega paramilitary groups went out of their way to target him and other media workers.

Chamorro said he was beaten by Ortega supporters. “I thought they were going to kill me,” he said in an interview.

Other journalists who had covered the protests were jailed and tortured. More than 100 fled the country. Several news outlets that were shut down by the government during that period have yet to resume normal activities, with armed police blocking the entrances to their newsrooms.

Despite putting his life on the line for La Prensa, Chamorro was let go last month in the newspaper’s latest round of layoffs.

It was a devastating end to a 28-year career at the paper, but Chamorro said he isn’t angry at his editors. “They had no choice,” he said.

Inside a small house in central Managua, a team of web journalists is carving out a rare bright spot in the country’s otherwise gloomy media landscape.

Unlike print publications such as La Prensa, all these journalists need to get their work to the public is a solid internet connection.

The website, Articulo 66, was founded in 2017 by longtime journalist Alvaro Navarro, who named it after the article of Nicaragua’s Constitution that guarantees freedom of expression. It is known for its short videos chronicling protests and for audio news briefs that are available for free on the messaging platform WhatsApp. The site has 254,000 followers on Facebook and in three years has grown from two paid employees to 12.

The site’s journalists have also faced harassment by government forces, said reporter Maria Gomez, who works from a desk wedged in the kitchen.

Gomez said she has stopped wearing a shirt that identifies her as a journalist. “The more we identify ourselves, the more we will be repressed,” she said.

To compete with Articulo 66 and other burgeoning web platforms, and to get around the embargo, La Prensa has plunged headlong into the digital age. It has moved more resources to its website and recently became one of a few newspapers in Central America to put up a paywall. So far it has just under 6,000 subscribers in a country of 6 million. Its print circulation is 15,000, down from 42,000 a few years ago.

Emiliano Chamorro, the journalist who was let go from La Prensa, says he plans to start his own news website. The costs are lower, he said, and online publications are harder for the government to censor.

His 24-year-old daughter Martha is studying to be a journalist. “Why not study graphic design, or marketing?” he asked her at first. “It’s dangerous right now.”

But when she insisted, telling him that she felt it was her civic duty, he was filled with pride.

“It’s a heroic profession,” he said on a recent day after paying her tuition at Central American University. “We put our bodies on the line.”

On Feb. 7, La Prensa’s publisher got a phone call. It was from a Catholic leader who has led negotiations between Nicaragua’s opposition and the government. He said authorities at the customs office were releasing the newsprint and ink.

The government again offered no explanation, and did not respond to The Times’ requests for comment.

Some on the staff of La Prensa think their editorial worked because it was generating international outcry. Others say the government may have made the concession because it fears new U.S. sanctions.

When the giant rolls of newsprint arrived in several trucks at the newspaper the day after the phone call, the whole staff stood outside, cheering. The next day, La Prensa ran the headline: “The paper has been liberated!”

For a brief spell, the staff members felt relief. But they know difficult times lie ahead. The newspaper is still operating in a recession and with a vastly reduced staff, and over the last year and a half it lost crucial advertisers. There is ongoing repression.

“It’s only a moment of happiness, it doesn’t mean everything is going to be OK,” said Cinthya Tórrez, a reporter who covers the Ortega government for La Prensa. “The fact is we still can’t go in the street and we still can’t ask the authorities questions because they might beat us.”

She said it has been difficult to stay focused on her work amid such uncertainty about the paper’s future.

“It’s an amazing story,” she said. “In the middle of all this, we’re just trying to do our job.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.