On the 75th anniversary Friday of the end of World War II in Europe, talk of war is afoot again — this time against a disease that has killed at least a quarter of a million people across the globe.

Instead of parades, remembrances and one last great hurrah for veterans now mostly in their 90s, it’s a time of coronavirus lockdown and loneliness, with memories bitter and sweet — sometimes with a lingering Vera Lynn song in the background.

For so many who went through the horrific 1939-1945 years and have enjoyed relative peace since, Friday felt at times as suffocating as the thrill of victory was liberating three-quarters of a century ago.

‘We are at war!’

It sounded like a cry from some past bellicose era or a Hollywood movie, but instead it was French President Emmanuel Macron speaking in a March 16 national address. He used the phrase “we are at war” six times to emphasize the threat of COVID-19 to his country as he announced a lockdown well-nigh unprecedented since World War II in its restrictions on personal freedoms.

Former U.S. Army medic Charles Shay was listening to Macron at his home close to France’s Normandy D-day beaches, where he fought in perhaps the most momentous day of the war in Europe — the June 6, 1944, landings of Allied troops in Nazi-occupied France.

Now 95, he said surviving D-day at 19 taught him this much: “When my time comes, there is not much I can do about it.” Yet Macron’s comparison didn’t fully fit his experience.

“World War II was created by a madman who thought he could take over control of the world,” Shay said. But with the virus, “we still don’t know why we are dying.”

Cloistered in his village of Bretteville-l’Orgueilleuse amid purple wisteria and pink peonies, he feels frustrated at all the cancellations that won’t let him see fellow veterans on Omaha Beach in the coming weeks — aging friends he might never see again.

It is thus across much of the world, with parades scrapped from Moscow to London and the United States.

‘We’re the last remaining veterans’

The sense of wistful melancholy hangs as a heavy, dark cloak over the countries that were victorious in 1945.

In few regions is V-E Day celebrated with more fervor than in the former Soviet Union, whose Red Army paid a terrible toll before the final breakthrough to Berlin. Eight time zones east of Normandy, Valentina Efremova, 96, lives among the memorabilia of her Great Patriotic War when she was a nurse caring for front-line Soviet soldiers.

She still dresses for the occasion, with numerous medals pinned to her chest.

Efremova had also been counting on something better so late in her life and is downcast about the chances of being able to attend some last worthy ceremony.

“We’re the last remaining veterans. We won’t be able to celebrate the 80th anniversary,” she said.

‘We were living with a permanent fear’

Some say today’s younger generations should put things into perspective when lamenting lockdown hardships such as closed barbershops, restaurants, bars and gyms. Many still have full fridges, and a strange knock on the door will likely be nothing more sinister than an online order delivery.

Contrast that to the experiences of Marcel Schmetz and Myriam Silberman. Through a twist of geographical fate, Schmetz’s family home became part of German territory as the Nazis invaded Belgium, and although he was too young, his brother Henri, at 17, had to join the German army — a potential death sentence.

“So we succeeded in hiding him at home while we had German soldiers around our house practically every day. He remained locked up like that for a year and a half,” Schmetz said.

He now runs a war museum with his wife, Mathilde, where part of the Battle of the Bulge, Hitler’s last bid to change the tide of the war, took place. Schmetz has re-created the old family room, where a mannequin dressed as Henri is sitting. But what was supposed to be the highlight of the year is now spent in isolation in the shut-down museum.

The current-day war comparison especially grates on 82-year-old Silberman, who as a child had to hide behind a fake identity in Belgium’s southern city of Mons for three years because she is Jewish. If discovered, she would likely have been deported and killed.

“Today’s generation might think that there is maybe a link, but this is incomparable,” she said. “I was 5 years old, but I could go out as the danger did not come from the air we breathe. The danger came from potential traitors. ... We were living with a permanent fear, even as children.”

‘Red wine — vino rosso!’

Amid the bleakness of the pandemic, some veterans still know how to win the 2020 war, too — spurious comparison or not.

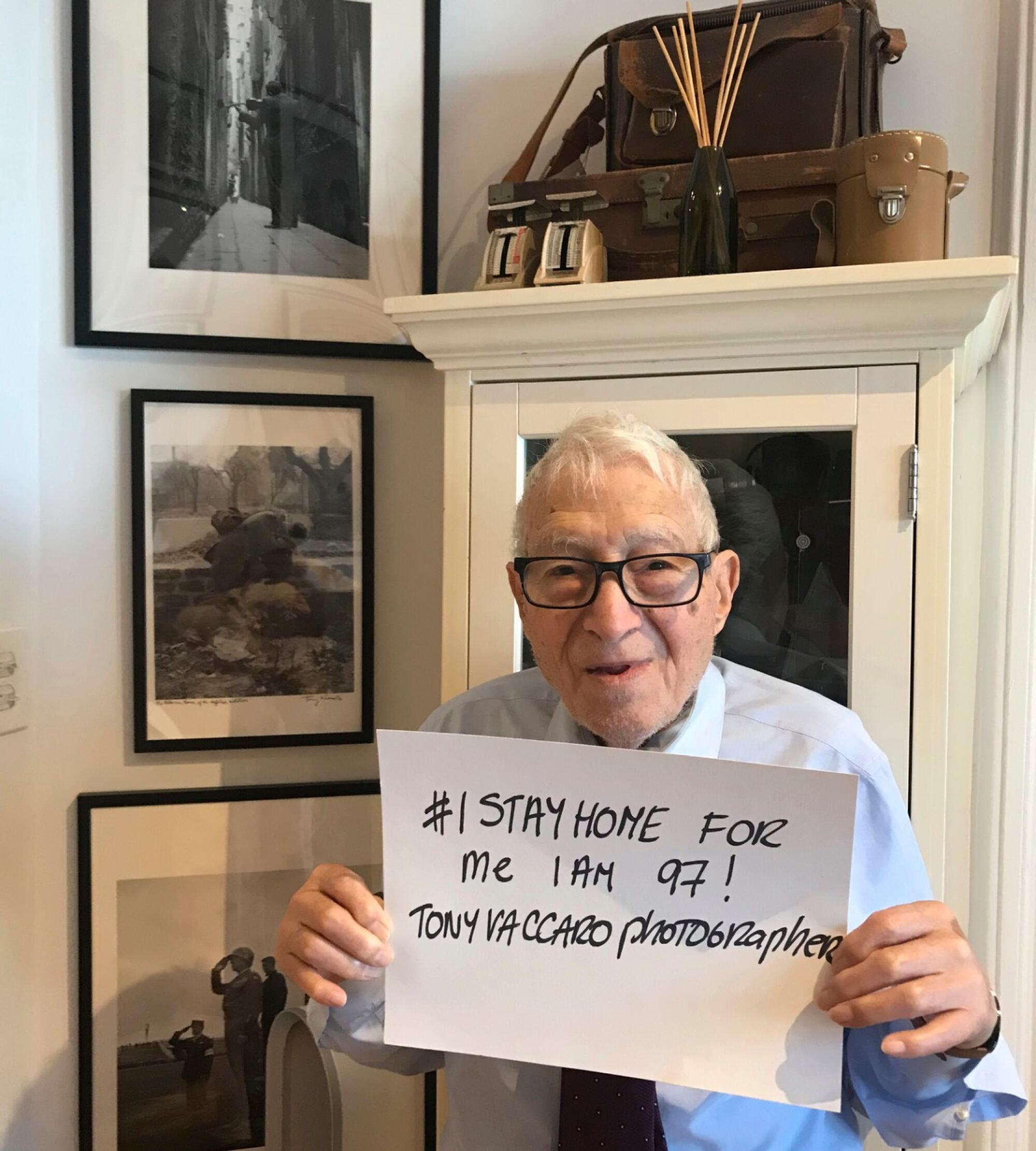

Take Tony Vaccaro, 97. He was thrown into World War II with the 83rd Infantry Division, which fought, like Charles Shay’s unit, in Normandy, and then came to Schmetz’s doorstep for the Battle of the Bulge. On top of his military gear, Vaccaro also carried a camera, and became a fashion and celebrity photographer after the war.

COVID-19 caught up with him last month. Like everything bad life threw at him, he shook it off, attributing his survival to plain “fortune.”

But for the longevity that is allowing him to celebrate the 75th anniversary of V-E Day he has a different explanation. “Wine,” he said from his home in Queens, N.Y. “Red wine — vino rosso!”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.