In Darfur, fault lines intersect and inflame

One side of Muhajeria is a ghost town. The only sign of life is the occasional animal left behind when thousands of people fled last month. Most huts have been plundered; hundreds have been reduced to ashes. Straw fences lie tumbled in ruins as wind blows through emptied streets.

Not far away are the “winners” in the recent fighting here. At first glance, their side of town seems equally dismal. Families live under scraps of plastic sheeting with limited food and water. All around are half-destroyed homes.

Yet they consider themselves the happiest people in Darfur. They were chased away three years ago and now are back.

“I may have nothing, but it still feels great,” beamed Adam Mousa, 40, a father of seven who arrived two days earlier.

The 20-day battle for Muhajeria, one of the biggest clashes in Darfur in recent years, is a window into the complexities of the Darfur conflict and the difficulty of resolving it. Its facets include rebel factionalism, government manipulation, tribal tensions, an environment of impunity -- and at times, disregard for the suffering of thousands of people.

At a U.N. peacekeeping base less than a mile from where homes were being systematically burned, commanders said they knew nothing about it -- though everyone in Muhajeria had seen the plumes of smoke.

“It’s a very complicated, multilayered story,” said Toby Lanzer, the U.N. humanitarian chief for Darfur, of Muhajeria’s recent turmoil.

The Darfur conflict started in 2003 with a rebellion against Sudan’s Arab-led government in Khartoum. President Omar Hassan Ahmed Bashir is accused by the International Criminal Court of unleashing a brutal campaign against the rebels that killed 35,000 people and led to the deaths of another 100,000 through disease and starvation.

When Muhajeria erupted in January, news reports focused mostly on government airstrikes and attacks by pro-government militias known as janjaweed that have been responsible for much of the violence in Darfur, a western region of Sudan.

But according to witnesses and victims, janjaweed played a relatively minor role here.

Instead, the battle started as a struggle between two Darfur rebel groups. The government escalated the violence with a weeklong bombing campaign that caused more terror than damage. And finally, the most destructive phase appears rooted in long-standing tensions between two Darfur tribes vying for land and resources.

Both tribes, the Zagawa and Birgit, had been victims of the janjaweed. Now they’re employing the same scorched-earth tactics against each other.

By the time the violence ended last month, about 30 civilians and dozens of combatants had been killed, and an additional 30,000 people were left homeless.

“That’s the way it goes here,” said Neimat Shafi, 40, a Muhajeria resident from neither tribe, as she rode a donkey through an abandoned neighborhood in search of straw and sticks. “One side burns down the homes of the other, so the other does the same thing in revenge. And it goes on and on.”

In 2005, Muhajeria, which in normal times has a population of about 40,000, came under the control of rebel commander Minni Minnawi, who leads a faction that signed a 2006 peace deal with the government.

Since the peace deal, Minnawi has been distrusted by all sides, ignored by the government and hated by his former rebel allies. In particular, Minnawi is at odds with Khalil Ibrahim, an Islamist hard-liner with the Justice and Equality Movement, or JEM, the best-armed rebel army in Darfur. Before joining the rebellion in 2003, Ibrahim was an ally of Khartoum, leading Islamic militias blamed for killing hundreds of southern Sudanese during the 21-year north-south civil war.

Each of them claims to be the rightful leader of Darfur. So tensions were high Jan. 15, when JEM troops arrived at Muhajeria saying they wanted water and rest. That night they launched a surprise attack, driving out Minnawi’s forces.

In town, few were sorry to see Minnawi go. Residents say his administration was characterized by corruption and excessive taxation.

But the arrival of JEM was no cause for celebration. The government tolerated Minnawi’s control of the city because of the peace deal. It would not give JEM the same courtesy.

“As soon as they arrived, some people started leaving,” said Hamed Asadig, 29, a teacher who fled town and now lives at a displacement camp.

JEM had used such tactics before. In early 2008, the rebel group invaded three towns near the Chadian border and then abandoned them as soon as the government attacked, leaving civilians unprotected and bitter.

To no one’s surprise, airstrikes on Muhajeria began a few days later, targeting rebel positions on the outskirts of town. When JEM troops passed through the nearby village of Shawa, the government dropped 27 bombs on the hamlet in one day.

In total about a dozen civilians died in airstrikes around the region.

Thousands of Muhajeria residents sought protection around the U.N. compound. At one point, the government ordered the peacekeepers to leave so it could escalate the bombing. The U.N. refused, but its troops remained on the sidelines.

“It would have been suicidal to get involved,” said Maj. Samuel Oky, commander of the U.N.’s Muhajeria base. “We’re not here to fight.”

Under pressure from the international community, JEM finally withdrew. On Feb. 4, government forces entered the town.

Almost immediately, Muhajeria’s Birgit community, a pro-government tribe, made its move against the Zagawa, who are largely pro-rebel.

In 2005 and 2006, nearly 25,000 Birgit had been driven out of the city by Minnawi’s forces. His Zagawa followers, who had migrated to escape drought in the north in the 1980s, took over Muhajeria and destroyed the square brick houses of the Birgit, replacing them with their own round mud huts.

Now, with assistance and protection from the government, Birgit militias began ransacking Zagawa neighborhoods, according to Zagawa witnesses and U.N. officials. As soon as the Zagawa left, Birgit began setting the Zagawa homes on fire -- sometimes with help from janjaweed.

“They started this fight,” said Ishak Adam, 37, son of a Birgit sheik who recently returned. “We will finish it.”

Many see the government’s hand in the tribal war. Resettling the Birgit puts Muhajeria into the hands of a “friendly” tribe and enables the government to claim that more Darfur residents are “going home.”

“Is the government playing a game of chess [with the tribes]?” asked one top U.N. official who did not want to be identified.

There is also speculation about the Zagawa exodus from Muhajeria, which appeared well-organized rather than spontaneous. U.N. officials think Minnawi pressured his supporters to move to his last stronghold at Zam Zam displacement camp near the city of El Fasher in order to consolidate his political strength.

Large trucks quickly arrived to ferry people to Zam Zam, said the U.N. official.

The migration has created a humanitarian crisis at Zam Zam, where shortages of food, water and healthcare are resulting in several deaths a week.

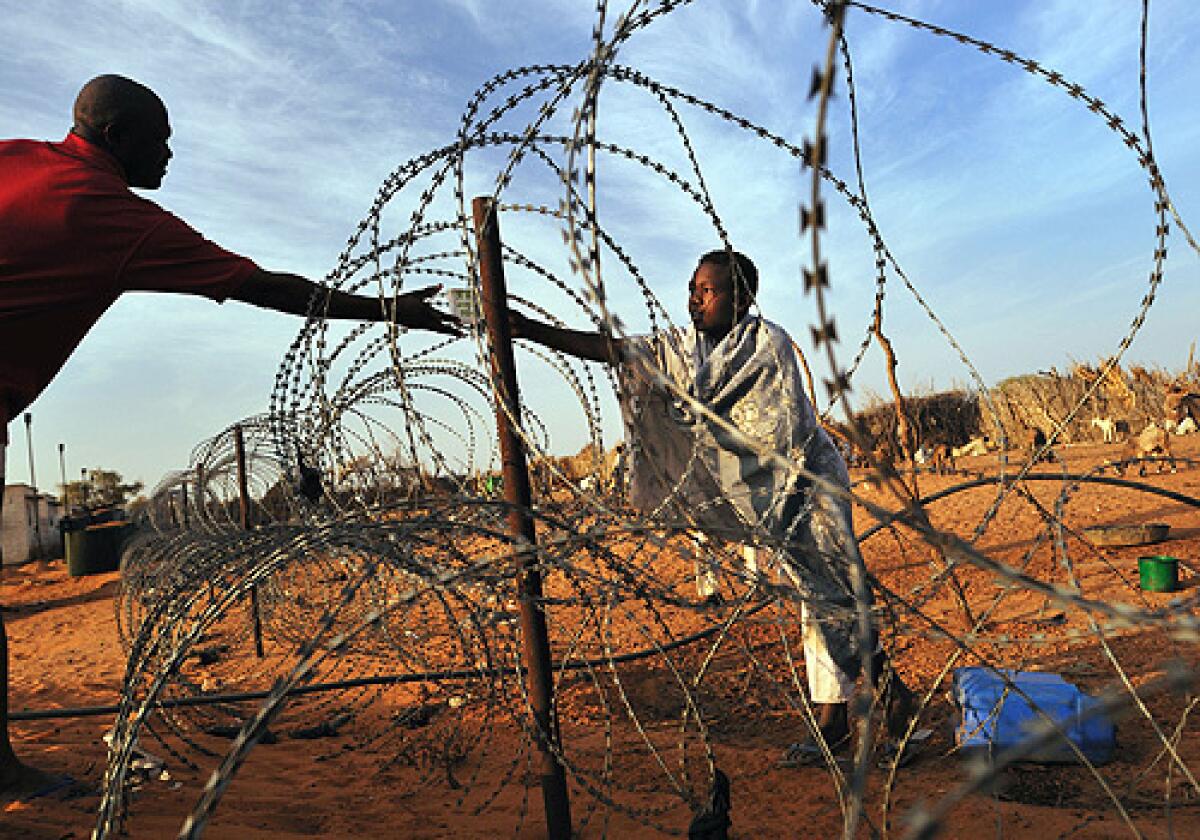

In Muhajeria, only a handful of Zagawa remain, mostly hiding in a couple of mud huts pressed against the razor-wire fence of the U.N. base. Some boys stayed behind to take their high school graduation exam while others say they missed the trucks and lack the means to move.

“We stay inside mostly because we are so afraid,” said Omer Issa Muqtar, 30. “If we go out, maybe they will kill us.”

This month, a friend who ventured to the city to feed his donkey was shot in the head by Birgit militia, Muqtar said.

U.N. peacekeepers in Muhajeria maintained that no homes were being burned until journalists showed them at least 200 that witnesses said had been torched in the last three weeks. Even then, some peacekeepers dismissed the destruction, suggesting the fires might have been accidental or set by fleeing Zagawa.

“Nothing has been reported to us,” Oky said.

Meanwhile, returning Birgit are settling next to their old homes with dreams of rebuilding. Under a thorny tree, eight newly arrived Birgit women chatted happily as they sorted peanuts for the upcoming planting season. Less than 30 feet away were the remains of burned Zagawa homes. Asked what happened, they just shrugged.

“This has been Birgit land for 200 years,” said Adam Zakaria Ahmed, 35, his face dusted with dirt as he dug a deep hole for a new home. Stacks of building materials lay nearby.

His family had been living in a displacement camp for nearly three years and he said he was eager to start a new life.

“I’m not leaving again,” he said. “It’s good to be home.”

edmund.sanders

@latimes.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.