Ramadan, court rulings ease tensions of Guantanamo hunger strike

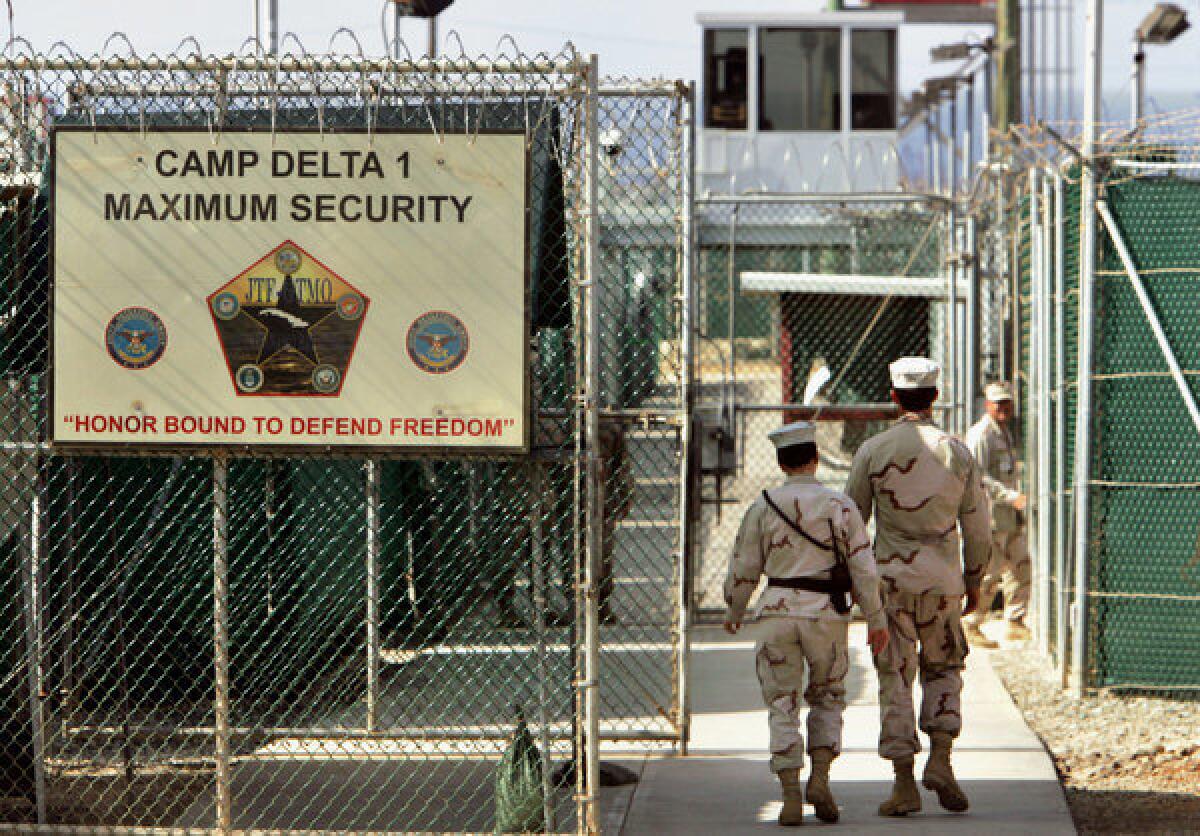

Weak from lack of food and worn down by months of harassment, the 100-plus hunger strikers at the Guantanamo Bay prison complex in southern Cuba scored symbolic court victories this week as their nearly 5-month-old protest against indefinite detention stretched into the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.

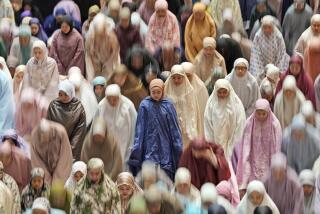

Military jailers at the U.S. Navy base have been force-feeding 45 detainees whose refusal of food – most since February – has taken its toll on their health and attitude toward compliance with the rules of detention. In all, 106 of the 166 foreign prisoners at Guantanamo have been classified as hunger strikers, having refused at least nine consecutive meals, although most voluntarily shared a meal Friday to break the daytime fast together.

Lawyers for four detainees – all cleared years ago for transfer out of the prison – had appealed to the federal courts for an injunction against force-feeding of the strikers, especially during the daylight hours of Ramadan when the faithful observe a dawn-to-dusk fast. A separate legal complaint cited rough handling and invasive “genital pat-downs” of detainees during transport to meetings with their lawyers as concerted efforts to deter prisoners from exercising their right to meet with counsel.

On the force-feeding issue, U.S. District Judge Gladys Kessler said Monday that she lacked the authority to intervene in the prisoners’ “conditions of confinement,” which federal law leaves to the discretion of the government. But she deemed the practice of force-feeding prisoners “a painful, humiliating and degrading process.” She observed that only President Obama could step in to end the hunger strikers’ treatment, and she encouraged him to do so.

On Thursday, in a sharply worded opinion, U.S. District Judge Royce Lamberth responded to detainee complaints of physically intimidating search procedures and rough handling of detainees in transit as interference with the prisoners’ legal right to counsel.

“The search procedures discourage meetings with counsel and so stand in stark contrast to the president’s insistence on judicial review for every detainee,” Lamberth wrote. “The court … will not countenance the jailer’s interference with detainees’ access to counsel.”

The British legal rights charity Reprieve had complained in reports backing the allegations in both cases that the detainees’ prolonged hunger strike was being punished with an increase in forced cell extractions -- a SWAT-team-like invasion to remove a recalcitrant prisoner for feeding -- as well as involuntary medications and solitary confinement.

In what may have been a response to the upbraiding judicial rulings, the joint task force that operates the prison complex relaxed a lockdown that since April had isolated the 75 prisoners in the communal detention area in their individual cells for all but two hours a day. The men were allowed to break their fast after sunset and pray together, according to task force officials.

“No detainees are fed during daylight hours during Ramadan. This is a commitment we intend to uphold, just as we have done with the limited few hunger strikers during past Ramadans,” said Lt. Col. Todd Breasseale, a Pentagon spokesman.

The detention center spokesman, Capt. Robert Durand, reported that the atmosphere at the prison was quiet.

“If there is more peace at Guantanamo this week it’s surely because of Ramadan,” said Oakland attorney Jon Eisenberg, who represents, along with Reprieve lawyer Cori Crider, the four men who sought a court injunction against force-feeding.

Eisenberg attributed the military’s refraining from breaking the Muslim daylight fast with force-feedings to pressure brought by the legal actions and Reprieve’s dissemination of a video by rapper Mos Def that graphically demonstrates the process by which Guantanamo medics force tubing through the nose and throat of a prisoner and pump liquid nutrients into the stomach.

The “enteral feeding,” as the military refers to the twice-daily procedure, takes as long as two hours because of the elaborate restraints required to keep the recipient confined to the purpose-built “restraint chair.”

Eisenberg noted that the Pentagon lawyers had made clear in their filings with Kessler’s court that they were retaining the option of force-feeding during daylight if they were to encounter “operational issues.” With little more than 10 hours of darkness each night and 45 men to whom the force-feeding is supposed to be administered, “that’s an operational issue,” Eisenberg said of the potential to run out of darkness before the feedings are finished.

Although more than 100 prisoners remain classified as on hunger strikes, Lt. Col. Sam House told reporters Friday that 99 had taken food voluntarily within the previous 24 hours. It was unclear whether that signaled a winding down of the protest or a temporary tactical retreat to recover enough strength to get off the military’s roster of those deemed in need of force-feeding.

ALSO:

Lebanese medical group says being gay is not a disease

Russian activists voice support for Snowden’s asylum bid

Pakistani girl shot by Taliban claims triumph over terrorists

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.