Families of the missing say they are stonewalled by Mexico state authorities

A candle has been burning for almost a year in the modest front room of the tiny two-bedroom apartment that Guadalupe Reyes shares with her husband, Bernardo, and their 10-year-old daughter, Tania.

Next to the candle is a picture of their older daughter, Mariana. Her 19th birthday was this month, but the family hasn’t seen her since she left their house in a working-class area of the Tecamac municipality, in the state of Mexico, nearly a year ago. She went that day, Sept. 17, to a photocopy shop no more than a 10-minute walk away. After she had been gone an hour, her parents launched a frantic search that continues to this day.

They reported Mariana’s disappearance the next morning, but authorities suggested she had probably run off with her boyfriend.

“The authorities show very little humanity [toward us]. The first thing the police do is question those who go missing, their honorability.”

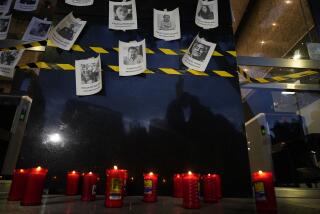

About 25,000 people have gone missing in Mexico since 2006, according to estimates by the government and human rights groups. Not clear is how many of them may have been victims of foul play, but some fear that many are dead because of the high levels of violence since federal crackdowns against drug cartels that began that year.

One of the most high-profile cases happened in September last year, when 43 students from a rural school in the southern state of Guerrero were hauled off by Iguala police believed to be working with a drug gang, causing national and international outrage.

In the state of Mexico, more than 1,200 women were reported missing in 2011 and ‘12, and the state has one of the nation’s highest rates of hate crimes against women. For families like the Reyeses, the anguish of not knowing where their loved ones are or what might have happened to them is only exacerbated by the authorities.

In early January, Guadalupe and Bernardo Reyes were told by the prosecutor’s office that Mariana’s remains had been found in a putrid-smelling canal called Rio de los Remedios, a short walk from their house. Hers were just some of dozens of human body parts found after the river was dredged by authorities in October 2014, a month after Mariana went missing.

“We asked to see her remains but they told us that they had already been buried. And when we asked to see photos they said we couldn’t see them, and when we asked to know more about the investigation they said it was ‘too delicate’ and ‘complicated,’” Guadalupe Reyes said, The authorities told them to just “accept the facts.”

“When I went to see the case file, it was completely empty. There was no investigation.”

She asked that the remains be exhumed and studied by independent forensic scientists, and the family is awaiting the findings.

“Whatever the results of those tests are, it’s going to be bad news,” she said.

Abril Caldino Rodriguez, 15, also went missing in Tecamac. She vanished in May 2011 after heading to an Internet cafe. When her mother, Isela, reported the disappearance to police, they also suggested Abril had run off with her boyfriend.

An agonizing two years later, Abril’s mother was informed that the girl’s remains had been found. But DNA testing showed that the state forensic team had made a mistake: The remains were actually those of a man. Isela said she found out the remains were not her daughter’s only by studying the case file. She was never formally notified by anyone in the prosecutor’s office.

“The truth is we still have no idea [what happened to Abril]. I don’t know whether she’s dead or alive.”

Last month, the state of Mexico activated a legal protocol called a “gender alert” acknowledging that something had to be done about the number of women and girls going missing or being killed in some parts of the state.

Authorities have yet to determine what those measures will be, but Dilcya Garcia Espinoza, the prosecutor who oversees the investigation and processing of disappearances and hate crimes against women in the state, said, “We’re activating a brigade with an intense focus within this agency to change things, to create a situation where investigators are getting in touch with the families of victims, rather than the other way around.”

Garcia Espinoza wouldn’t comment on the specific cases of Mariana and Abril and the way their families say they were treated by state investigators, but said that her door “is always open” to receive complaints.

There is no comprehensive federal database of the missing. The federal government is working on legislation on forced disappearances, one of the primary functions of which would be to create such a database, as well as to make forced disappearances a crime in every state, which is not currently the case.

But people with missing family members don’t hold out much hope that things are going to improve.

Mario Vergara’s brother Tomas disappeared from the small town of Huitzuco, in Guerrero, in July 2012. Since then, Vergara has joined civilian search groups that came together to look for the missing students when they felt authorities weren’t doing enough. He worked with Miguel Angel Jimenez Blanco, a leader of the search efforts, who was fatally shot in early August in his hometown.

Vergara has also assisted in government-backed investigations.

“They don’t know what they’re doing. It’s like asking a shoe-shiner to perform heart surgery.

“If these are the people looking for our missing family members, they’re never going to find them.”

Bonello is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.