ON A MISSION: Rediscovering the original El Camino Real through La Jolla

It’s right in front of us — a forgotten chunk of the original El Camino Real’s roadbed.

Well, it’s not right in front of us. It’s at the bottom of a deep canyon, north of the Geisel Library at UC San Diego, that’s surrounded by 80-foot walls sloping 35 degrees downward and mined with rattlesnakes, Africanized bee nests, cacti and things that are even less fun than that.

Somewhere between 50 and 200 feet long, this roadbed has not felt a car tire since before the university was plopped all around it in the ‘60s. Yet its white lane markings are still clearly visible.

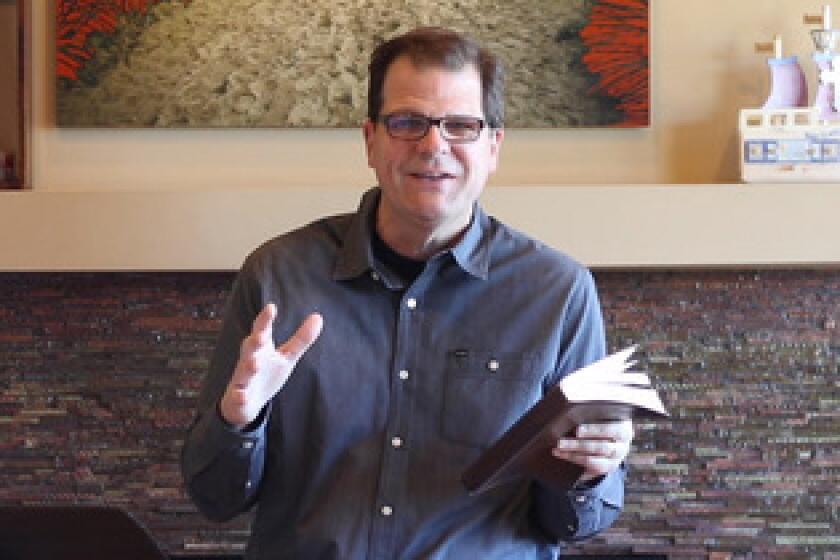

“You and me are taking a selfie on that!” enthuses my companion on this mission, Edie Littlefield Sundby, the La Jollan who published a 2017 book, “The Mission Walker” (Harper Collins), about her experience walking every one of El Camino Real’s 1,600 miles from deep in Mexico up to Sonoma in 2016.

“This should be a cakewalk compared to Loreto,” she says. “Human beings were just not meant to be there.”

On her El Camino Real route through La Jolla, Littlefield Sundby took currently functioning surface streets. But that’s only because, she says, “I had no idea about this.”

El Camino 101

Popularly, El Camino Real (the Royal Highway) refers to the path taken by Franciscan friars between the 21 missions, two pueblos and four presidios established in the 500 miles and 55 years between the founding of the first Alta California mission in San Diego in 1769 and the last one in Sonoma in 1824 — back when our state belonged to Mexico, and Mexico to Spain.

The missions were spaced so that each was within a day’s walk (or about 30 miles) of the next. According to the August 1914 issue of “The Journal of the American Institute of Architects,” the plan was “to establish a cordon of missions a day’s journey apart,” which “led to the development of a road, following, in all probability, previously established crude trails, and which … became the recognized highway of official travel.”

Most of the missions were built by Father Junipero Serra and 16 other priests from Mexico City’s College of San Fernando, who arrived in Loreto in Spring 1768. Their intention was to establish Catholicism as the region’s dominant religion, and to convert Native Americans to a European way of life.

As a 1/8 Choctaw who was raised Christian in rural Oklahoma, Littlefield Sundby could be expected to harbor conflicting emotions about these goals. But, she says, it’s a waste of time imposing modern values on people who were trying to do good according to the rules of their time.

“You can talk about what happened 250 years ago, or you can put your eyes on what’s happening today and say never again,” she says. “That’s one thing Junipero Serra used to say: ‘Always forward, never back.’”

And that’s exactly what we’re trying to figure out as we stare in the distance at the former El Camino Real — how to move forward towards it. A feature of the directly surrounding canyon walls are cliff-like drop-offs at the bottom that we need to avoid. The easiest way would be to split up so that one of us can direct the other down from across the canyon.

“No,” Littlefield Sundby says. “We’re taking that selfie together.”

To the north of us, El Camino Real picked up again at the canyon bottom parallel to the I-5, on the other side of the landfill wall that completed Genesee Avenue’s on-ramp. But that path is long obliterated, as was the path El Camino Real took through Sorrento Valley connecting it to the road that, in Del Mar right up to the entrance to Mission San Luis Rey in Oceanside, is still called El Camino Real.

Proving it

Of course, the road we’re staring at in the distance didn’t meet its demise as El Camino Real. It was part of the Rose Canyon Highway that was paved in 1930 over the old stagecoach road and renamed Pacific Highway shortly thereafter. The I-5 was built over most of that highway, but not this part.

An 1889 survey map of San Diego shows the stagecoach road, which ran to Los Angeles since before the Civil War. (There was no coast route yet, as the map shows, and no cars to take it if there were.) Still, it’s impossible to know for certain the location of a Native American footpath so long ago without a map from the time.

“To have a semblance of authority, you'd need to find something pre-1849,” said Barry Ruderman of Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps, “but I know of no maps with the requisite scale from this period.”

However, Ruderman points out that the route north would have been dictated by the fastest route northward from San Diego to Oceanside. “This would have been as straight a line as the missionaries could have found,” he said.

Ever wonder why the train tracks cut a five-mile east-west horseshoe shape through University City and Sorrento Valley while traveling north-south? It’s because, prior to the construction of the I-5’s gravity-defying bridgery in 1964, there was no straight line possible to take through Rose Canyon. The ascent was too steep — as it would have been for Franciscans and their mules and caretas (the traditional freight wagons of colonial Mexico).

“After a short time, we ascended a hill well covered with grass,” wrote Father Juan Crespi in his diary on July 17, 1769. “Our road then took us across mesa lands, some open pasture and others covered with groves of scrub oaks, wild rosemary, and to us unknown bushes.”

The Franciscan and his small padre cadre were in the midst of what historians regard as the first voyage of Europeans through California.

So the Franciscans were led, by their Native American guides, up a less-steep trail, west of Rose Canyon, that led up to a mesa. That this trail was probably what became Gilman Drive was not lost on the El Camino Real Association, which placed one of its Mission Bells, a series of markers celebrating the original route, by what is now the entrance to the Residence Inn by Marriott at 8901 Gilman Drive in the early 1900s.

“We should have brought gloves!” Littlefield Sundby yells from behind me. “Also a hiking pole and a machete!”

Incidentally, about half of the sentences Littlefield Sundby utters today start with “we should have.” The other half start with “be careful of the.” The most recent of the latter sentences ended with “prickly pear.”

But it arrived too late to prevent a thicket of thorns from slowly stabbing into my pants and even my Timberlands. I will survive, although the other hardships we will face today include being buzzed by a black military helicopter filled with angry-looking officers wondering what we’re doing, and receiving a UCSD citation for parking in a space that I clearly displayed a permit for. (Have I mentioned that I’m more of an indoorsman?)

El Camino: Real or mythical?

After all this, there may have never even been a real El Camino Real after all. I feel I should at least mention this possibility, since historians vigorously debate it.

“The idea of a continuous road that connected all the missions as part of this concrete plan — I wouldn’t be surprised if someone said this would be a great idea, but as far as evidence of what was on the ground, which really begins to come to us only in the era of roadbuilding, there was nothing there,” said Matthew Roth, historian at the Automobile Club of Southern California Archives.

“From Santa Barbara to the Mexican border, it’s a little over 240 miles,” Roth explained. “That was the first stretch of the Pacific Coast Highway to open in 1928. There were literally hundreds of bridges necessary. There were no bridges across these drainages. So any notion of continuous road that doesn’t include these stream crossings is ridiculous.

“Maybe they crossed by bridges that left no archeological evidence,” Roth continued, “but during this period, the way to travel north and south was by coastal vessel. There’s ample evidence of that.”

The placement of the mission bells — an idea dreamed up by Los Angeles writer and activist Harrie Forbes and backed by the California Federation of Women's Clubs, which funded the one on Gilman — were partly responsible for what Roth calls this “booster myth.” They were an early 1900s marketing effort to refashion El Camino Real into a tourist highway to attract commerce.

"El Camino Real was a product of the same impulse that gave us the Spanish Colonial Revival in architecture — imparting an exotic hue to the region as a way to attract more tourists and settlers," Roth said.

“Nonsense!” Littlefield Sundby snaps. “That’s a lie and you and I both know it. There was totally an El Camino Real.”

This is not an argument that can be settled by a newspaper article. But one thing is becoming abundantly clear today: There is no trail down to this abandoned stretch of El Camino Real that Littlefield Sundby and I can locate. We’re on our fourth attempt to descend the canyon, but every trail we think we find dead-ends into ever-thickening sagebrush, yerba santa and assorted tall and prickly plants that I can’t identify but that obscure the drop-offs.

As much as I want to make contact with the original El Camino Real, cracking my skull on it is not what I had in mind. But Littlefield Sundby tells me she actually wouldn’t mind dying today.

“It’s better than dying in bed,” she says.

The big reveal

Littlefield Sundby was diagnosed with gallbladder cancer and given three months to live — back in 2007.

“It was in eight organs,” she says, “my colon, my liver, my bile ducts. Because it was Stage 4, it spread all over the place. There was no operating.”

I probably should have dropped this bombshell earlier, but then you would have thought of this as an article about cancer, and Littlefield Sundby as someone who is disabled by it. And neither is true.

“Walking is how I’m still alive,” she says, reporting that it helped her endure 79 rounds of chemotherapy and four major surgeries at Stanford Cancer Center. “The only way I could withstand the chemo was to walk.”

It was while walking the canyons around Stanford that Littlefield Sundby discovered what became the purpose of her life’s final years.

“Every time I walked, I’d see these mission bells and I’d get really curious about it,” she says. “There are mission bells every mile up there. It’s almost as if they were beckoning me to this mystery — what is this all about?”

I hear the cough because I’m listening for it. But it’s only there when Littlefield Sundby sits or stands perfectly still — not when she walks or hikes. The cancer has returned in her left lung, the one that wasn’t removed by surgeons.

“So what if I die?” she asks. “Everybody’s dying.”

For the third time today, I lose my footing and slide into a plant that saves me from sliding or tumbling. In this case, it’s NOT a patch prickly pear (thank goodness), but I’ve had enough. I’m not ready to die today, and I convince Littlefield Sundby to turn back.

The padres didn’t succeed either — at least on their first mission.

“There were some native peoples that welcomed them with open arms, and there were some that were shooting arrows and screaming with remarks the padres couldn’t understand but they knew it was not a welcoming gesture,” said Tony Falcon, archivist at Mission San Diego, who estimates that “only 10 percent” of the native peoples converted or even accepted the padres and their strange culture.

“They were not that welcome, I guess,” he said.

As Littlefield Sundby and I beat a retreat, she promises that we will return — with the proper tools — and take that selfie on the original El Camino Real one day.

That’s a question of faith, on many levels, and I can’t think of a more appropriate note upon which to end this mission.

Get the La Jolla Light weekly in your inbox

News, features and sports about La Jolla, every Thursday for free

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the La Jolla Light.