A ‘catalytic moment’ for art and culture

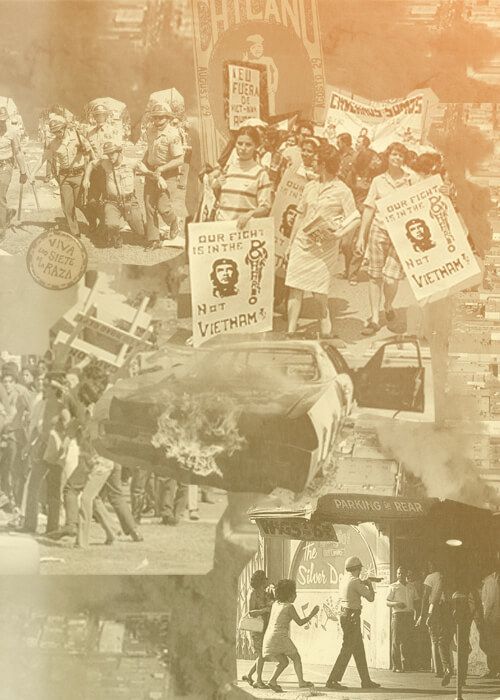

In murals, theater, photography and music, the Chicano Moratorium influenced art of its time and our time too.

It was a day that began with exuberance and then exploded in violence. It was a date that would mark in Los Angeles a before and an after.

On the morning of that date, Aug. 29, 1970, Judithe Hernandez was 22, an undergrad at the Otis Art Institute (now the Otis College of Art and Design). She and some friends had gathered at her family’s Eastside home so they could head as a group to the National Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War. The East L.A. rally was intended to protest the high toll the war was taking on Mexican American life. There would be speeches, music and folclórico dancing — a day, says Hernandez, that was filled with “expectation and empowerment.” Her mother offered to make her and her friends breakfast before they took off for “the parade.”

The Times is taking a look back at the legacy of the Chicano Moratorium in 1970. See more stories

Judy Baca, then 23, was working as a roving art teacher for the Department of Recreation and Parks, holding workshops at Eastside community centers. The day of the Moratorium, she met up with a group of teens she’d been working with at Evergreen Recreation Center and together they began to march south to Laguna Park, where the rally was being held, joining a sea of protestors along the way.

Harry Gamboa Jr. had gotten to the park early. All of 18 years old, the artist was already a veteran of the “blowouts” of 1968, when Mexican American students had walked out of schools to protest the dire state of public education on the Eastside. Gamboa had played in Laguna Park as a child. Now he was back as an activist — and the mood was ebullient.

“You had people from the African American community, Japanese Americans that had been interned, veterans from various wars, Mexican workers,” he recalls. “You had everyone who was willing to protest the war against Vietnam.”

But the Chicano Moratorium ended in clouds of tear gas before it could start. Following a report that a liquor store had been robbed, L.A. County Sheriff’s deputies took action against the crowd. When the tear-gassing and shooting were all said and done, three people were dead. Among them: L.A. Times columnist and KMEX news director Ruben Salazar, shot in the head with a tear gas canister.

The Chicano Moratorium marked a seismic moment in the fight against the Vietnam War, the struggle against police brutality and in the Chicano civil rights movement. It also marked a transformational moment for art in Los Angeles.

The Moratorium shifted creative paths for those who were present and those who heard about it on the news or from friends. It fueled an urgency to make visible the Chicano experience, one that had largely been left out of the history books — an urgency that remains resonant at this time, when the Latino cultural presence in the U.S. remains evanescent, and when protesters around the world have taken to the streets in uprisings against police brutality.

The Moratorium “was a catalytic moment,” says Rita Gonzalez, a co-curator of the exhibition “Phantom Sightings: Art After the Chicano Movement,” held at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2008. “It was a massive grassroots generational response.”

In its wake emerged a wave of muralism, printmaking, photography, performance and music that engaged Chicano themes in ways both literal and abstract — changing the landscape of Los Angeles, and sparking the establishment of long-running Southern California arts institutions.

If you love Los Angeles, support our journalism.

The Times is dedicated to covering everything about our city, whether taking a hard look at its past or at what's going on today. Get unlimited digital access. Already a subscriber? Your contribution helps us make projects like this possible. Thank you.

“Artists began to find ways, whether they were painters or performance artists, to translate the movement visually,” says Sybil Venegas, a curator and historian of Chicano art who taught at East Los Angeles College (ELAC) from 1979 to 2013. “You had murals. There was Self Help Graphics and the Day of the Dead celebrations. It was taking culture to the streets — a culture that had been lost and assimilated out through horrible schools, racism and segregation.”

Self Help Graphics, in fact, came straight out of the Moratorium era. The community art space was launched by a group of printmakers — Sister Karen Boccalero, a Franciscan nun, with Carlos Bueno, Antonio Ibáñez and Frank Hernández — out of an East L.A. garage in 1970. By 1973, they had incorporated as Self Help Graphics, occupying an old gym in Boyle Heights where they had a printmaking atelier and space for exhibitions and performances (space that has been formative to generations of artists since then).

In 1973, Self Help staged its first Day of the Dead celebration, an event that has become a defining cultural happening.

“We completely changed how Day of the Dead is celebrated in the hemisphere,” says Karen Mary Davalos, a Self Help Graphics board member and chair of the Chicano and Latino Studies department at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. “In Mexico, it’s a private matter. But here it becomes a community event. Those processions are another alternative form of demonstration.

“It’s taking over the streets is what it is,” she adds. “It’s moving what had been private into the public space. And that kind of activity is what we get from the Moratorium.”

Embracing Roots

On the day of the Chicano Moratorium, Hernandez and her friends never made it to Laguna Park (since renamed Ruben F. Salazar Park). They ended up turning around after seeing swarms of police officers dressed in riot gear as they approached while a surging crowd fled the escalating violence on Whittier Boulevard.

But the experience “lit the fire,” says Hernandez, a painter and muralist who would later become the fifth member of the groundbreaking art collective Los Four with painters Frank Romero, Carlos Almaraz, Beto de la Rocha and Gilbert “Magú" Luján. “I measure everything from that moment as far as the movement was concerned.”

Growing up, Hernandez says she’d had a romantic vision of what it meant to be an artist, one steeped in a world of Renaissance masters. But the Chicano movement in general and the Aug. 29 Moratorium specifically pushed her to examine art history more critically. She and Almaraz, a friend and fellow student at Otis, joined Marxist study groups. She engaged one of her professors, Charles White, a painter known for his metaphysical depictions of the Black experience, in dialogues about art and representation.

For her thesis, she conducted an analysis of Mexican American cultural symbols. Her work became increasingly infused with images drawn from Mexican and Indigenous traditions, often focused on representations of women.

“There was no way we could stand by,” she says of that moment. “You must do something. You must step in.”

All of this arrived at a moment in which culture was on shifting ground.

The Black civil rights movements of the 1950s and ’60s, along with the farmworker movement and the rising Brown Beret movement, had drawn attention to issues of labor, inequity and police brutality. In the late 1960s, academic institutions such as ELAC, Cal State L.A., Cal State Northridge and UCLA were beginning to establish Chicano Studies courses and departments. In 1970, UCLA began publishing “Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies” (now in its 50th year).

In the artistic sphere, Mexican American artists opened art spaces dedicated to showing the work of fellow artists, such as Mechicano Art Center and Goez Art Studio.

Hear more from Times journalists. Watch our forum

The Times hosted a virtual forum on the Chicano Moratorium that featured authors of the series, including Daniel Hernandez, Carolina A. Miranda and Robert J. Lopez. Watch recordings via The Times Facebook page, YouTube or Twitter.

“Artists were processing the politics of the day, they were processing vernacular things, they were responding to the graphic impulses of the day, they were processing police suppression,” says LACMA’s Gonzalez. “The ability to respond to an event either in a poster form or in a mural — at that moment the murals were so dynamic and so responsive.”

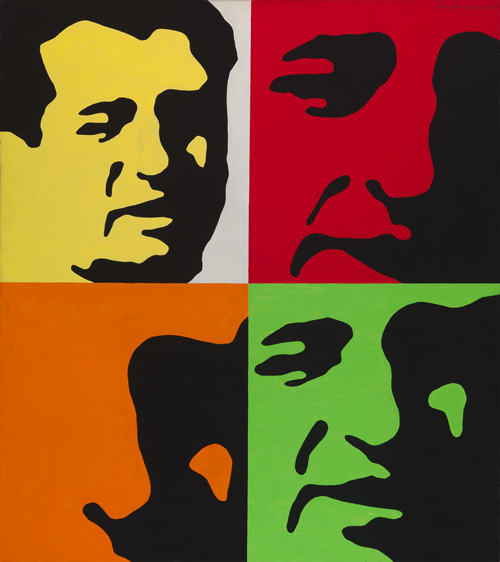

In 1970, the same year as the Moratorium, Bay area artist Rupert García created a painting of the fallen Salazar that shows an outline of the journalist’s face over a series of colored quadrants. (It’s now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.) Countless posters, paintings and prints have been made with Salazar’s visage since.

Likewise, the Moratorium directly figures in a now-famous Los Angeles mural.

“Black and White Mural” was painted in 1973 at the Estrada Courts houses in Boyle Heights by artists Willie Herrón III and Gronk (born Glugio Nicandro), two artists who would also become known for their work with the art collective Asco, of which Gamboa was also a member.

In filmstrip fashion, the mural fuses various elements, such as scenes from Marcel Carné’s 1945 film “Children of Paradise,” shot in France during the German occupation, with images of the Moratorium showing police outside of the Silver Dollar Bar & Cafe, where Salazar was killed.

Gronk told an interviewer for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art in 1997 that he wanted the mural to have a “cinematic, documentary” feel — “almost like a time capsule for that neighborhood. Like, this is what was experienced here at a particular moment in time.”

The mural boom

The “Black and White Mural” was one of hundreds of murals that appeared in L.A. in the 1970s. And key to that artistic outpouring was Baca.

Like Hernandez, Baca never made it to Laguna Park on the day of the Moratorium. Before she and her teen charges could hit Whittier Boulevard, they saw protesters running away from sheriff’s deputies, so the group hightailed it back to Evergreen Recreation Center.

Baca, at that point, had been active in civil rights causes and participated in at least one demonstration that had devolved into violence. But the sheer number of protesters that turned out for the Chicano Moratorium — at least 20,000 people — buoyed her like no other protest. “I’d never seen so many Latinos together in one place,” she says. “To see all of those people together, it was one of the most influential things in my life.”

In the years that followed, she helped launch key art programs for the city, working with at-risk youth to produce murals, first on the Eastside, then across Los Angeles: “We did over 400 murals and every artist got a small stipend ... and the kids got minimum wage.”

During the 1970s, she also co-founded SPARC, the Social and Public Art Resource Center, an arts nonprofit devoted to promoting activist work — be it murals, painting, photography or printmaking. (The center is still in operation, housed — not unironically — in a 1929 jail and police precinct in Venice.)

In 1974, Baca and a whole raft of collaborators (which included Hernandez) launched a decade-long project that transformed a portion of the Tujunga Flood Control Channel in North Hollywood into a half-mile-long mural that told the unvarnished history of California from pre-history to the 1950s, including panels devoted to Indigenous labor in the Spanish missions and Japanese American internment during World War II.

“The kids used to call that area the sewer,” says Baca. “It was the least valued place. And I said, ‘OK, we’ll take your least valued place and I will make it a national monument.’”

“The Great Wall of Los Angeles,” as the work is called, is now listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Baca is currently working to extend the mural so that the narrative can include the 1960s, “to the protests that are like the ones that are happening today.”

“We need this monument,” she says. “Where did I know that we needed this? The Moratorium.”

The camera's view

One of the Moratorium’s key transmitters has been the art collective Asco, which was founded by Gamboa, Herrón, Gronk and multimedia artist Patssi Valdez, and featured a range of collaborators in its 15 years of existence (1972 to ’87).

Gamboa was the group’s relentless chronicler. And he was in Laguna Park when the first tear gas canisters landed.

“People were choking for air,” he recalls. “It was blinding. ... Families nearby allowed people to flood in their yards — hundreds of people — and they allowed us to stay in their homes until the police filtered away.”

Simmering anger over brutal policing, unequal education and racist neglect finally explodes.

A Day of Rage in East L.A.That experience directly inspired the artist to pick up a camera and carry it at all times. “I had the idea that it would be really important to document on some level,” says Gamboa. “I could tell a story. But unless I had the pictures to prove my point, I’d be outvoted in any argument.”

That same year, he bought his first camera — a 35-mm Minolta 101. He ended up deploying it in the most unexpected ways.

Gamboa and his Asco collaborators created stylized photographic self-portraits that toyed with gender, style and representation. They created outlandish fictional film stills titled “No Movies” — before Cindy Sherman had thought to do the same. Gamboa snapped one of the group’s most famous images: “Spraypaint LACMA,” from 1972, when various Asco members tagged their signatures onto LACMA’s gleaming Modernist facade and Valdez posed fashionably alongside them — turning the museum into a giant work of Chicano art. (In 2011, LACMA hosted a major retrospective of Asco.)

In 1974, Asco members — along with regular collaborator Humberto Sandoval — staged a performance in a road median off of Whittier Boulevard, in which they sat around a dinner table in masks and elaborate makeup, the ambience ameliorated by a naked doll and a mannequin painted to resemble a skeleton.

“First Supper (After A Major Riot),” as the piece is titled, was held on the site of another anti-Vietnam War protest led by Chicanos in 1971, in which one man was killed and an additional 25 were injured by sheriff’s deputies — a protest in which Gamboa participated. It also happens to sit just four blocks from the site where Salazar was killed.

“The reason we went to that spot is because that’s exactly where I was standing when the police opened fire,” says Gamboa. Asco’s response was pointed but absurdist. “We wanted to create something that not only reflected on the Last Supper, but a madcap tea party from ‘Alice in Wonderland.’ It touches on Día de los Muertos and intermingles various other facets. All the young men there had managed to avoid Vietnam.”

The location — just off Whittier Boulevard — was significant in other ways too.

“When people talk about hip in L.A. in the ’60s and ’70s, they want to go to the Sunset Strip,” says Eric Avila, a historian who teaches in the Chicano studies department at UCLA. “But Whittier Boulevard was doing its own thing. A lot of people forget that.”

“The Moratorium,” he adds, “was part of a process in which Mexican American youth claimed Whittier Boulevard as their space.”

Asco claimed it in the name of art.

Missing histories

The idea of creating monuments for histories that are obscured or untold is an idea that has echoed among artists ever since the Chicano Moratorium. When Gonzalez was putting together 2008’s “Phantom Sightings” for LACMA, which examined work made in the decades after the Chicano movement, she says “there were so many artists dealing with this idea of the absent histories.”

The Chicano Moratorium, to some degree, has been an absent history.

While it has long been a topic for discussion in Chicano studies courses in higher education, the Moratorium has never really saturated the broader public consciousness.

But the 20th anniversary of the Moratorium in 1990, which took place against a backdrop of civil rights happenings, began to trigger a broader reconsideration of that history.

It was in 1990 that students and faculty at UCLA kicked off a 15-year struggle — one that included a hunger strike and sit-ins — to have Chicano studies formally turned into a department. Two years later, in 1992, the Los Angeles riots followed. Two years after that, Prop. 187, a xenophobic voter initiative that sought to deny undocumented immigrants public services, landed on the ballot.

On the cultural side, the groundbreaking exhibition “Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation, 1965-1985,” known as “CARA,” opened in 1990 at UCLA’s Wight Art Gallery. It’s believed that it was then the largest exhibition of Chicano work in a single museum setting. The show featured political graphics, painting, installation and photography from the 1960s through the ’80s, some of which touched on the Moratorium. The show included Garcia’s painting of Salazar, as well as a canvas from 1985-86 by Los Four member Romero, titled “The Death of Ruben Salazar,” which shows sheriff’s deputies aiming their weapons at the Silver Dollar. (It is now in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.).

That same year, two plays also tackled the subject of the Moratorium.

“The Silver Dollar,” by the collective Teatro Urbano, was staged at the site of the old Silver Dollar Bar & Cafe on Whittier and imagined the final moments of Salazar’s life. “August 29,” which featured set design by Gronk, was written collectively by members of the Latino Theater Company at the Los Angeles Theatre Center and told the story of a Chicana university professor who is writing a book about Salazar.

“We wanted to ask what is happening to our community when it is beginning to have a middle class — in relationship to the history of the movement,” says José Luis Valenzuela, who helped author the play and now serves as artistic director of the company. “A lot of us became professors because of the movement. We got to where we are because of the movement. It was a struggle to get where we got.”

“August 29,” interestingly, also served as valuable history lesson: “A lot of people didn’t know about Ruben Salazar before we did the play,” he says. “A lot of people didn’t know about the Moratorium before we did the play.”

To mark the 50th anniversary of the Moratorium, members of the LATC will stage a virtual reading of the play on the evening of Aug. 28. The following day, Teatro Urbano will restage the final scene from “The Silver Dollar” outside the site of the old bar on Whittier — now occupied by the Sounds of Music record store.

A new generation

If the Chicano Moratorium still echoes in present-day Los Angeles, it is partly through the work of artists who have served as vital tellers of the story.

Echoes lived on in “Cesar and Ruben,” a musical staged at the El Portal Theatre in 2003 that featured Salazar and labor organizer Cesar Chavez engaged in a dialogue in the afterlife. They lived on in “After the Gold Rush: Reflections and Postscripts on the National Chicano Moratorium of August 29, 1970,” a 2011 exhibition held at the Vincent Price Art Museum that brought together an intergenerational group of artists examining issues of equity, power and justice. They lived on in “Chicana Moratorium: Su Voz, Su Canto,” a 2016 concert organized by Martha Gonzalez of the band Quetzal, that presented songs and spoken word inspired by the women of the era.

“We as artists take the responsibility of transmitters of this knowledge through songs,” says Gonzalez. “Songs are ways of theorizing. Songs are a way of doing that beyond the academy.”

That concert inspired one of its participants, Alice Bag, a founder of the ’70s punk band the Bags, to write a corrido dedicated to Gloria Arellanes, a Brown Berets leader who broke away to co-found the women’s civil rights group Las Adelitas de Aztlán. She also wrote a powerful anthem directly inspired by the Moratorium called “White Justice.” The music video for “White Justice” connects the law enforcement excesses of the era to the ones happening today.

“This event was supposed to be folclórico dancers; it was supposed to be peaceful speeches,” Bag says of the Moratorium, which she attended at age 11 with her family. “It was a demonstration, not a riot. It was organized. Yet people got tear gassed and shot. It ended so badly.”

Vincent Ramos is an artist and curator who organized “After the Gold Rush” at VPAM in 2011. Now 48 and raised on the Westside, he was not yet born when the Chicano Moratorium took place. But in the ’90s, he went to see Teatro Urbano’s “The Silver Dollar” in East L.A.

“The whole Moratorium, and its reason for being, in response to the Vietnam War, was powerful to me,” Ramos says. “I had five uncles in Vietnam. ... I had one uncle who died there.”

Seeing “The Silver Dollar” established a sense of lineage, indirectly inspiring the show that he organized many years later.

“It was that generation — my generation — being exposed to the history of the previous generation, history that had taken place 20 years prior,” he says. “This bridge, if you will.”

A story passed from one generation to the next, as a song, in a play, through a painting, in performance.

“These things,” says Ramos, “they still resonate.”

Fifty years later, the echoes live on.