Burbank icon Harry Strickland dies at 100

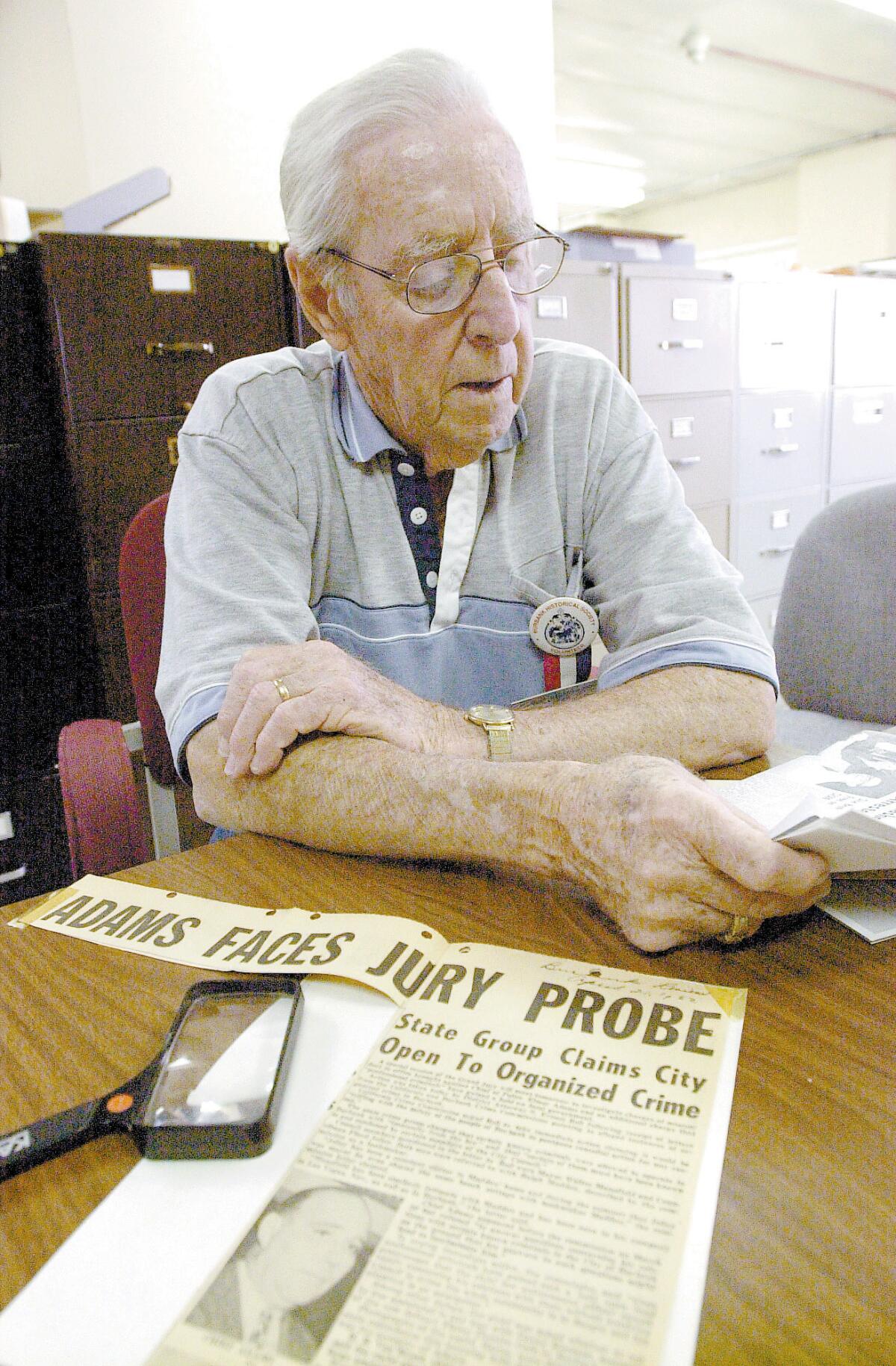

In this 2003 photo, retired Burbank Police Officer Harry Strickland looks over some news clippings from his career, as well as one involving Mickey Cohen and the Police Chief, Elmer Adams, who resigned amid allegations he was tied to Cohen and organized crime.

- Share via

Harry Strickland, a retired Burbank Police detective who busted up illegal gambling operations run by gangster Mickey Cohen in the 1940s and ’50s, died Monday. Strickland was 100 years old.

Not only was he a part of Burbank’s history, Strickland founded the Burbank Historical Society with his wife in 1973 and spent two years in the early 1980s restoring the 1887 Mentzer House, located in George Izay Park on Lomita Street, which is now home to the society’s Gordon R. Howard Museum.

“Working on the little house was what I enjoyed most,” he told Leader columnist Joyce Rudolph earlier this year in an article about his 100th birthday.

Strickland’s daughter Penny Rivera said he was the “work horse” of the museum even into his 90s.

A memorial for Strickland will be held at the museum at 11 a.m. Aug. 15. In lieu of flowers, the family is asking that donations be made to the Burbank Historical Society or a favorite charity.

The centenarian was born in Forest Hills, N.Y., in March 1915, and came with his family to North Hollywood about eight years later, then to Burbank in 1938. He joined the police force in 1940 and served until 1969, with a break during World War II to serve in the U.S. Navy as a radioman in the South Pacific from 1943 to 1945. After retiring from the police department, he worked for the Superior Court in Los Angeles for more than a decade.

It was as a Burbank police officer after the war, in 1948, when Strickland had a memorable encounter with the famous crime boss Cohen, which bears resemblance to a scene from a noir movie.

In a Burbank Leader article in 2000, Strickland told reporter Leslie Simmons that he and his partner, Sandy McDonald, had received instructions from then Police Chief Elmer Adams to check out the Dincara Stock Farm, an old horse stable on Mariposa Street and Riverside Drive, and raid it if they found evidence of gambling.

After coercing a lookout to bring them to the entrance — a door with a large peephole — the detectives heard a lot of movement and saw 50 people and “gambling paraphernalia,” such as roulette wheels and craps tables, according to a later account in 2003.

“I’ve given it a lot of thought, and in a way I’ve never forgiven Elmer Adams for doing what he did to McDonald and me,” Strickland said to Leader reporter Ryan Carter in that account, adding they had no radios, no backup and no vice squad. “I’m sure he knew who Mickey Cohen was. But he sent two policemen down there. Nobody in their right mind today would do that.”

Cohen confronted Strickland and McDonald at the police station about three arrests they made at the covert casino, Strickland said. He demanded to know what exactly Adams’ orders had been.

“That was the demise of Elmer Adams,” Strickland said.

About four years later, on the eve of a grand-jury investigation that connected him to payoffs from racketeers, Adams resigned.

Strickland married his wife, Mary Jane, in 1951. His bride of 64 years said this week she remembered that time in Burbank, calling Cohen “quite a little hoodlum.”

Harry Strickland was also involved in the investigation of the murder of Mabel Monohan, Rivera said in an interview this week. The murder inspired the 1958 movie “I Want to Live!,” in which Susan Hayward won a best actress Oscar for her portrayal of one of Monohan’s murderers, Barbara “Bloody Babs” Graham.

Rivera said her father wasn’t one to tell stories about his exploits, but was “just a sweet, dedicated man — dedicated to his family, dedicated to the museum, dedicated to the city.”

Besides his wife and daughter, Harry Strickland is also survived by granddaughter Michelle Rey and great-grandchildren Shaye Herriford, Robert Herriford and Jesse Rey, as well as several nephews and a niece.

Mary Jane Strickland said her husband was not a big talker or self-promoter, and “he was just a doer” who remained energetic until the last few months of his life. A back injury from a fall in the kitchen while bathing the dog began to slow him down.

“It’s hard to describe somebody who was so big in my life,” Mary Jane Strickland said. “I used to call him my silent man, my Gary Cooper.”