How the coronavirus flooded California and swamped L.A.

It started in Orange County a little more than a year ago.

With the sun long set and many residents in bed, the public health department posted a message on Twitter at 11:08 p.m. last Jan. 25. A traveler from Wuhan, China had tested positive for the novel coronavirus.

Twelve hours later in Los Angeles, Barbara Ferrer, the top public health official in America's most populous county, had an announcement. A second person returning from Wuhan had been hospitalized with the virus.

At the time, there were only four known cases in the United States. Some leaders, including the president, gave assurances that the virus would soon be snuffed out.

They were wrong. There have been 26 million confirmed cases and more than 400,000 deaths nationwide. In California, more than 3 million people have tested positive and 40,000 have died.

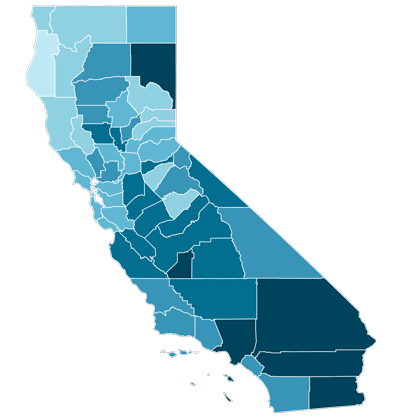

The Times has been tracking the numbers since the pandemic’s earliest days. A look back on the first anniversary of the outbreak shows how the spread across the state unfolded in four distinct chapters, leading to a massive winter swell which the state is still recovering from.

An outbreak in the Bay Area spreads south

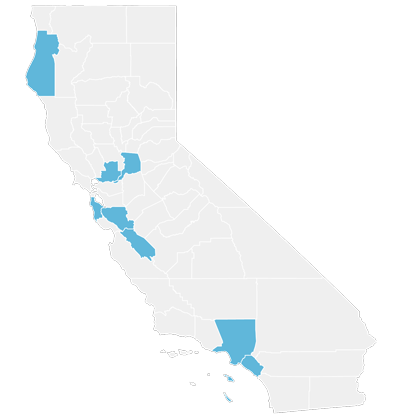

The virus made its first footholds in the San Francisco Bay Area, where several cruise ships carrying infected passengers were quarantined at sea.

Hopes that the virus could be contained aboard the ships were soon dashed. It began spreading in Bay Area communities in late Februrary, leading to the highest infection rates in the state.

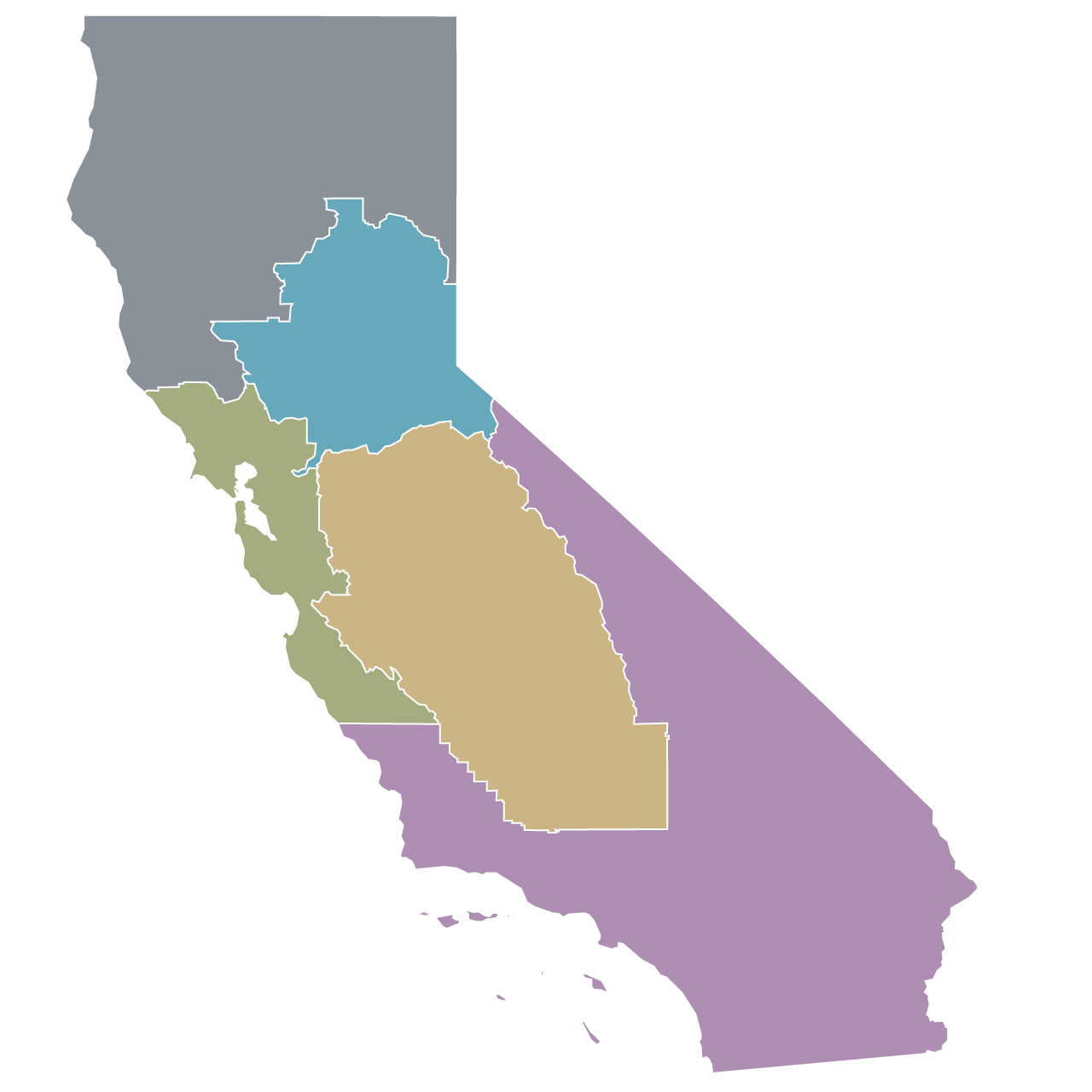

California’s five regions

Northern

California

Greater

Sacramento

Bay Area

San Joaquin

Valley

Southern

California

In early March, the first coronavirus-related death was reported in Placer County. Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a state of emergency. With cases piling up in Silicon Valley, Santa Clara County officials banned mass gatherings.

Talk began of “social distancing” in Los Angeles but the L.A. Marathon went on as planned on March 8. At the time, there were 14 known cases in the county.

As infections continued to spread, leaders began to take more decisive action. On March 19, Newsom ordered all Californians to stay home. It wouldn't be enough.

At that time, there were 1,200 cases statewide. Four days later, cases had doubled. Two weeks later, on April 1, they had quadrupled and Southern California had shot past the Bay Area to establish itself as the new epicenter in the state.