Holocaust survivor talks about horrific years in a dozen concentration camps

- Share via

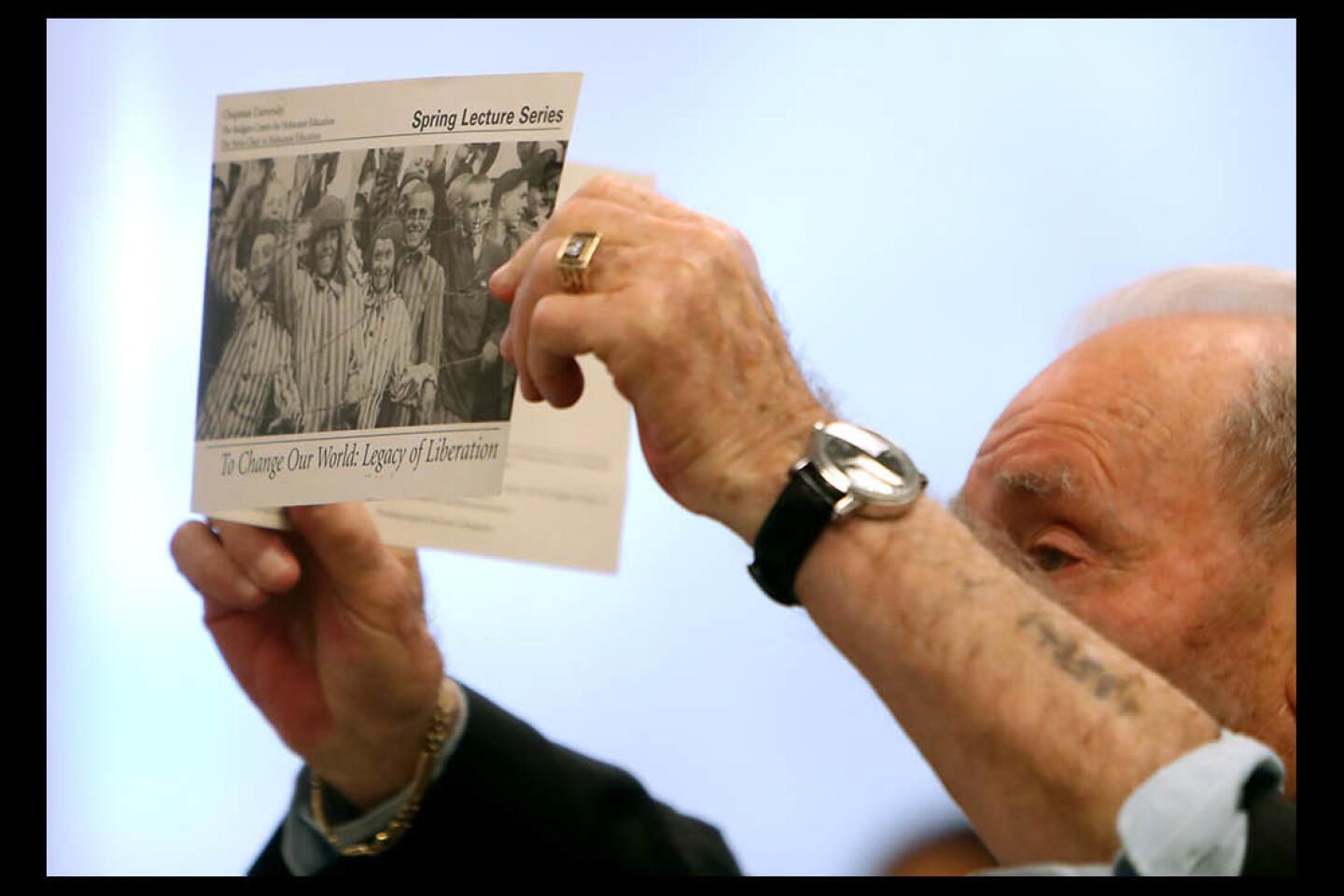

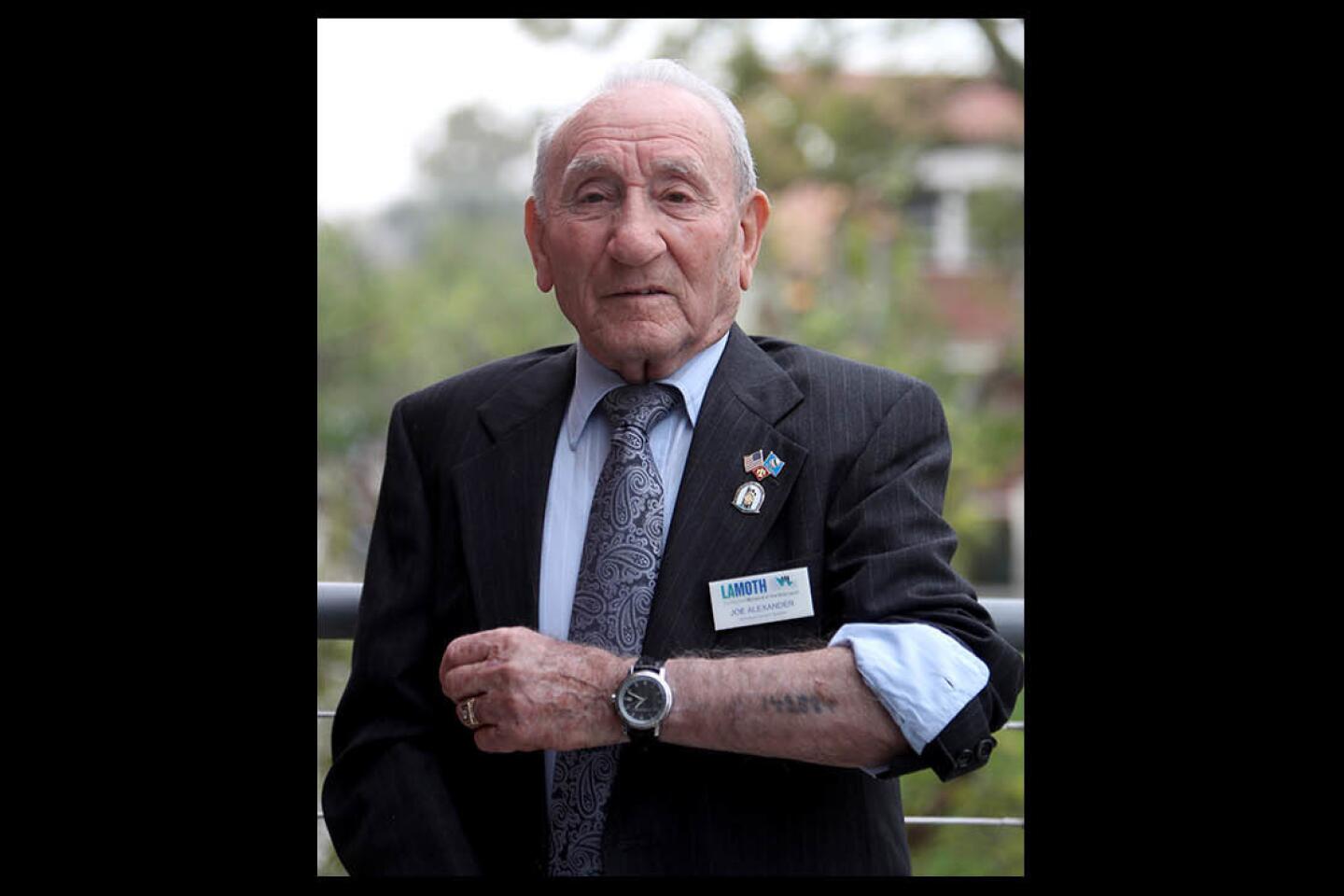

As he stood in the center of a lecture hall, Joseph Alexander rolled up a sleeve of his light blue dress shirt. The 96-year-old raised his arm to begin telling his story.

“14284,” read a chain of numbers inked on his left forearm. The tattoos, remnants of a tragic case of dehumanization, wasn’t just any number, but a reminder of what happened to him and many others in concentration camps during World War II.

The ink on the tattoos has aged, but decades later, his tales of surviving 12 concentration camps, including Auschwitz, were still fresh.

Alexander was the featured speaker during a Holocaust Remembrance Day event, sponsored by Woodbury University’s United Nations Assn. and the Center for Leadership last week.

“One of the [foundations] of prejudice is ignorance,” said David Meyerhof, with the Burbank Interfaith Forum and Burbank Human Relations Council. “People don’t know what the effect of it is. During the Holocaust, for example, people were put in camps and gas chambers, all because of ignorance.”

As one of the few remaining survivors of the carnage against Jews, Alexander has become a leading voice in Holocaust education, especially in high schools and middle schools.

“When I speak, I let [students] know that they met a survivor,” he said. In this case, personal memories and experiences are used as tools to fight hostility and misinformation.

“There’s so many Holocaust deniers out there, but evidence is still in existence, the camps are still in existence. How can they deny it?” he added.

Growing up, Alexander said he lived what he called a “comfortable, good life.” It wasn’t until September 1939 that, in a matter of one night, the lives of thousands of Jewish families were turned upside down.

Sadly, Alexander’s Polish hometown of Kowal was one of many communities targeted at that time. He was only 17 years old. What once was an ordinary, “happy” lifestyle, would become a compilation of terrible memories, sorrow and a struggle for survival.

Warm, home-cooked meals were replaced with “potato-peel soup,” nothing from which a human body could find nourishment. The prisoners were deprived of basic essentials for survival. Water was one of them.

“They put us up in a field, and the ground here was moist,” Alexander recalled. “Whatever means, you had a knife, a spoon and if anything, you could dig up some mud, flip the bottom of your shoe — you squeeze through to get a little water.”

To survive the famine, one had to seize opportunities. However, that too, was often forbidden.

“The next day, we started to walk again, and we reached a river,” he said. “We stopped to get some water. Two of our people went a little too far into [the water]. They got shot, killed in the river. [The guards] thought maybe they’re gonna escape.”

Pastimes such as playing soccer were soon replaced with heavy-duty jobs in labor camps, where prisoners built airports, railroads and dams — all with threats of death and starvation.

“In Warsaw, we were taking down burnt buildings brick by brick and cleaning them up to put them in stacks of 8 to 10 feet,” Alexander recalled. “And so, when I got a fever, I was sitting two or three days behind the stacks of bricks to get over the temperature.”

It turned out that he was suffering from typhus. During his time shuffling through camps, Alexander also suffered from blood poisoning and skin conditions.

Illnesses transmitted during days-long cable car transits between one camp to another were fatal for many. Each “box” of the cable car was packed with 40 to 50 individuals at a time, resulting in exhaustion, starvation and disease. Seeing dead bodies had become common sights for Alexander.

“Maybe 40% of people died in the wagons every day,” Alexander said.

He described the time he made a life-saving choice at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp.

Upon arrival, prisoners were ordered to form two lines, which often would indicate the fate of those individuals. The elderly and ill were dispatched to the left side, and those who looked more promising, to the right. Alexander initially was with those to the left. Realizing that he was going to be trucked into a crematory to be killed, Alexander counted on his instincts and moved into the line with the stronger prisoners.

As he made his way through the Warsaw ghetto, numerous concentration and labor camps, Auschwitz and even liberated Poland, Alexander said he saw the worst in humanity.

In 1945, American troops freed Alexander and other Jews, and he moved to the United States in 1949. Later that year, he was joined by his cousin, the only other surviving member of the Alexander family.

In the United States, Alexander continued his career as a tailor. He has since paid numerous visits to Auschwitz and Dachau, where he spent most of his time as a prisoner.

When asked why he thought he made it through such a harrowing ordeal, he replied, “I came back because I survived, Hitler didn’t.”

Sahakyan is a contributor to Times Community News.