Robert F. Kennedy beamed.

“Now it’s on to Chicago and let’s win there!” The senator had won the California primary, a crucial step before the Democratic National Convention just two months away in Chicago. In the early morning hours of June 5, 1968, Kennedy held up his index and middle finger, flashing a “V” for victory sign at the crowd, and departed the stage of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles to the sound of chants.

Within minutes, cheers gave way to screams.

‘My God, not again’

Boris Yaro had arrived at the Ambassador Hotel at 10:30 the night of June 4. The Los Angeles Times reporter was off-duty and hoping to grab a photo of Kennedy. Hours later, after Kennedy took the stage and addressed the crowd, Yaro shouted at the senator to hold up two fingers. He missed the shot.

Yaro saw an opening to the kitchen. Maybe now he’d get his chance.

Gunshots rang out.

Six people were wounded by the gunfire. Only one would die.

“The reaction I had was, ‘My God, not again.’”

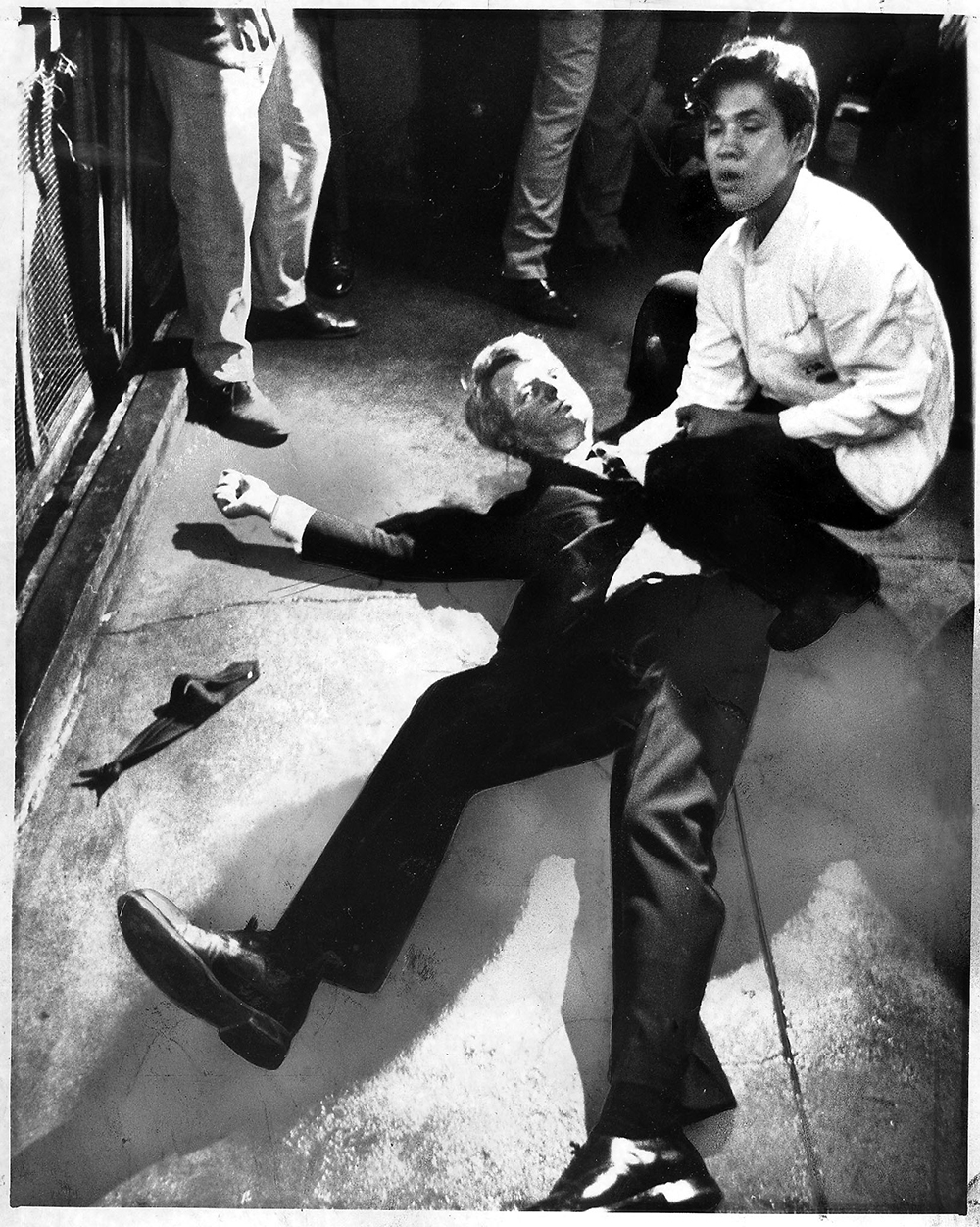

Yaro saw Kennedy slip to the floor as bystanders grabbed the shooter and slammed his hand down on a freezer top, knocking the gun loose.

“I reached out and picked up that revolver,” Yaro said. “I remember the grip was still warm.”

William Barry, Kennedy’s bodyguard and a former FBI agent, grabbed the gun. Rosey Grier, the football player, reportedly sat on the gunman until police arrived.

Kennedy was on his back, drenched in blood. Yaro took six frames.

He headed to The Times’ office. He turned over his film and, after describing what he had seen to the reporter writing the story, went into the darkroom to see the images.

There, in the darkness, he wept.

‘It was a different world back then’

John Nickols heard the news on the radio that morning. When the Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy got to the Hall of Justice, everything was in disarray.

The man who would later be convicted of killing Kennedy, Sirhan Sirhan, was being held upstairs.

Sirhan, a 24-year-old Jordanian refugee living in Pasadena, had written a manifesto three weeks before.

“Kennedy must be assassinated June 5, 1968.”

The date was the first anniversary of the Six-Day War fought between Israel and its neighbors Egypt, Syria and Jordan.

Presidential candidates didn’t typically have police protection in 1968. President Lyndon B. Johnson had secretly requested funds for protection for all candidates weeks before the shooting.

But there was no extra security that night at the Ambassador Hotel.

At the Hall of Justice, Sirhan was given extraordinary protection. Authorities well remembered that President John F. Kennedy’s assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, was killed by Jack Ruby while he was in custody.

“There was a lot of fear that Sirhan would be dispatched before trial, for lack of a better term,” Nickols said.

The windows to Sirhan’s room were covered by steel plates. Nickols heard that the deputies were patted down before entering his room, and that everything Sirhan ate came from a can.

“They were afraid that someone would go in and shoot him and make a name for themselves.”

‘My heart was so broken’

Donna Chaffee thought Kennedy would win the November election. She assumed she would be working in the White House after graduation.

Chaffee had worked for Kennedy’s campaign while attending George Washington University. When she transferred to UC Berkeley, she remained active. She saw Kennedy days before he went to Los Angeles, and got her parents tickets to the Ambassador Hotel event. They would end up driving some of the Kennedy children to the airport after their father had been shot.

At 1:44 a.m. on June 6, Kennedy died. Chaffee’s future, and that of many others, was upended.

“After he was shot and killed, I just didn’t have the stomach for politics for many years.”

Chaffee hopped a plane to New York to attend the funeral with Kennedy’s former staffers. Coretta Scott King was there, only two months after her husband, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., had been killed.

Chaffee rode the train to Arlington National Cemetery and watched as Kennedy was laid to rest.

“You go through your life and you try to do the right thing, and then you come against choices where you don’t know what to do. He comes to mind, and points you in the right direction.”

Fifty years later

The Ambassador Hotel was demolished in 2006. Years before, the 23.5-acre landmark starred at the center of a property debate between real estate developer and future president Donald Trump and the Los Angeles Board of Education. Eventually, the Board of Education won ownership over the land.

Sirhan remains in prison. Recently, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. revealed that he visited the convicted gunman at the Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility near San Diego last December. At the end of their meeting, he came to the conclusion that a second shooter attacked his father — a theory that many, including one of the wounded, have long-believed.

Today, on the former site of the hotel stands the Robert F. Kennedy Community Schools — six small schools, each with a mission for social justice.

A mural of Kennedy reaching toward outstretched hands adorns a wall in the school library. Outside stands a memorial dedicated to him, with words from a 1966 speech he gave in South Africa.

“Few will have the greatness to bend history; but each of us can work to change a small portion of the events, and in the total, all of these acts will be written in the history of this generation.”

The Times learned of Chaffee’s and Nickols’ stories from our 1968 call-out. If you have a memory you’d like to share from 1968, leave a message at (951) 39-HeyLA/(951) 394-3952 or write to us here.

Video and audio editing: Yadira Flores, Robert Meeks and Myung J. Chun