Robert Kennedy assassination: a time of terror, disbelief and sorrow, much of it live on TV

Josh Mankiewicz’s father, Frank Mankiewicz, served as Robert F. Kennedy’s press secretary. He was with Kennedy the night the presidential candidate was shot at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles.

- Share via

Like many members of the Baby Boomer generation, Josh Mankiewicz awoke on June 5, 1968, to the news that Sen. Robert F. Kennedy had been shot shortly after celebrating his California Democratic presidential primary win.

Mankiewicz was 12 years old at the time, and the first report created anxious moments in his Washington, D.C, home. His father, Frank Mankiewicz, served as Kennedy’s press aide and was with the candidate that night at the Ambassador Hotel in downtown Los Angeles. After the shooting was first reported at 12:15 a.m. Pacific time, Josh’s mother was on the phone through the early morning hours trying to get word on his father.

“In the first early hours of this there were a lot of people that thought my dad had been one of the first people who got shot,” said Mankiewicz, now 62 and a correspondent for NBC’s “Dateline.” His family was relieved when Frank Mankiewicz appeared on TV that morning to give his first press briefing, standing on the roof of a police car in front of the Good Samaritan Hospital. Inside, surgeons were attempting to save Kennedy’s life.

Frank Mankiewicz was a somber but steady presence in the 25-hour span after the shooting, a period filled with terror, disbelief and sorrow — much of it seen live on TV.

Television news in 1968 had already been saturated with violent images — from the bloody Tet Offensive in South Vietnam to the urban riots after the murder of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis. But Robert Kennedy’s shooting — coming 4½ years after his brother President John F. Kennedy was cut down by an assassin — immersed viewers in the chaos and sadness of the dark, turbulent year in American history as no other event had.

RELATED: The assassination of Robert Kennedy, as told 50 years later »

“That was the moment when I began to wonder if the country was coming apart,” said Fox News anchor Chris Wallace, who, as a 20-year-old college student, watched his father, CBS News correspondent Mike Wallace, report on the story in the network’s New York studio.

For ABC News correspondent Sam Donaldson, who had covered the calamitous events that shook the nation throughout the decade, the shooting did not come as a total shock.

“You just sort of expected it,” Donaldson said. “When they called me at home early in the morning, Washington time, to say ‘Bobby has been shot, get down to the bureau,’ I was upset about it. On the other hand my reaction was not ‘my God, how could this have happened?’ Well, in the decade of the 1960s, anything could happen and it did.”

RELATED: A timeline of 1968, a year of anger, grief and change »

The 140 hours of coverage provided by the three broadcast networks over four days — from the first frantic reports to Mankiewicz’s updates to Kennedy’s funeral — presaged how America would absorb traumatic events in years to come on 24-hour cable news and then social media.

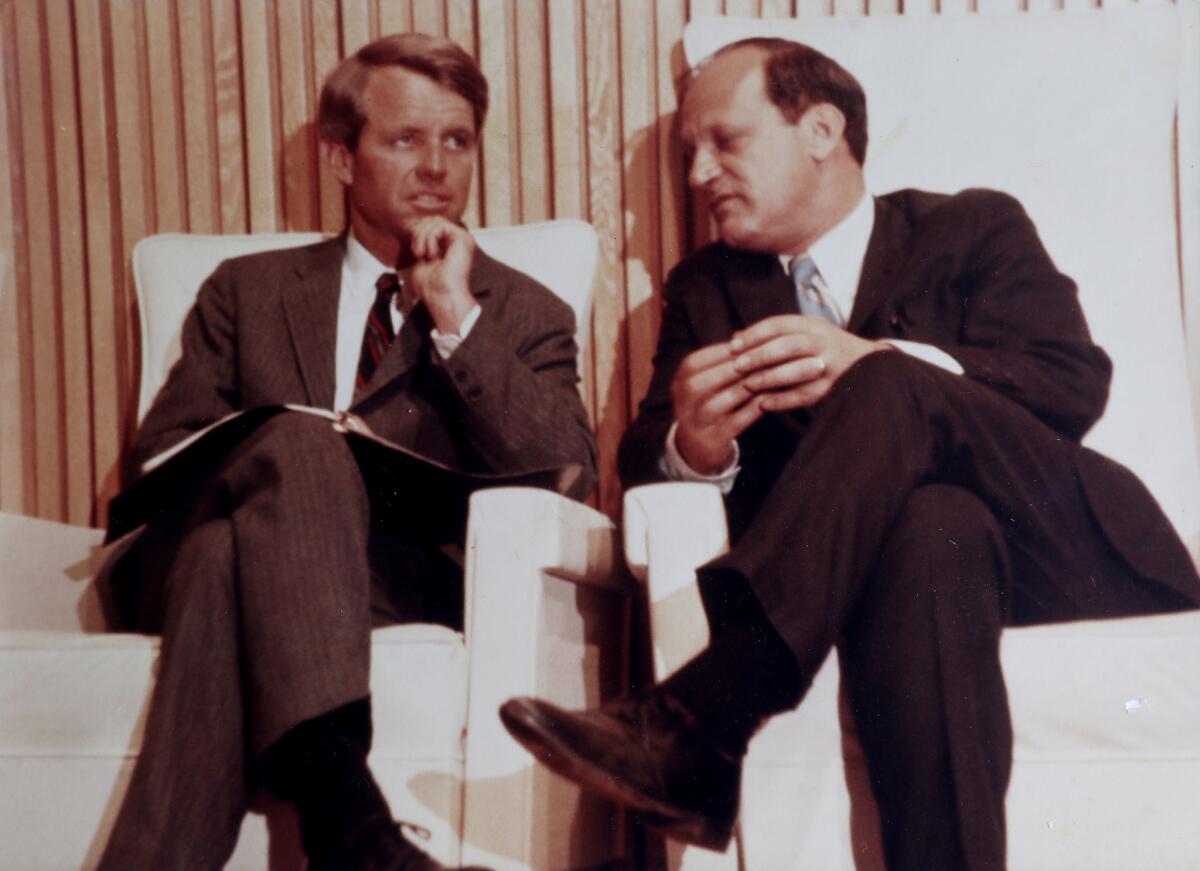

Robert Kennedy, right, walks with his press aide, Frank Mankiewicz, in the San Fernando Valley on June 3, 1968.

Kennedy had given his victory speech after midnight and the networks had switched back to their studios or signed off the air once the senator from New York left the ballroom to make an exit through the kitchen. Kennedy was greeting kitchen workers when Sirhan Sirhan, a 24-year-old Palestinian from Jordan, approached and fired a .22-caliber handgun. Five other people, including William Weisel, an associate director for ABC News, were hit.

Los Angeles station KTLA was taping in the ballroom when the shooting occurred, with reporter Larry Scheer giving the first eyewitness account. ABC, CBS and NBC correspondents and cameramen scrambled to get back in position to cover the story amid screams, sobbing and cries of “oh no” that filled the Embassy Ballroom.

In New York, Wallace and his CBS colleague Walter Cronkite had gone home for the night, but Joseph Benti, who had covered the primary returns, was at a bar and grill across from the CBS Broadcast Center, waiting for his shift as morning anchor.

“I was the only on-air guy left, and I was trying not to get too loaded so that I could be on at 7,” recalled Benti. “The network was off the air and someone came in and said ‘Bobby Kennedy has been shot.’ We rushed back and told the network to come back on.”

It would be hours before footage and images from the Ambassador kitchen were processed and shown on the air. With no immediate pictures to rely on, TV correspondents in the ballroom tried to sort through information from grieving Kennedy supporters.

When a man told CBS News correspondent Terry Drinkwater he had given last rites for Kennedy — a common practice among Catholics in life-threatening situations — many in the crowd at the ballroom believed it meant he had already died. Some women in the room fainted.

Weisel gave his ABC News colleagues Frank Reynolds and Howard K. Smith a telephone interview from the Kaiser Sunset Hospital before going into surgery for his wound. “I really thought I was going to die instantly because blood was shooting every place,” he told them.

Correspondents were able to talk to the doctors who attended to Kennedy in the kitchen before he was placed in an ambulance. They noted that he was alive and his pulse still strong. But it was not until Mankiewicz appeared at 2:30 a.m. Pacific that Kennedy’s true condition became known. Saying doctors described him as “very critical,” Mankiewicz explained how one of the two bullets that struck Kennedy entered behind his right ear and lodged in his brain.

Early news reports suggested Kennedy would survive. ABC’s science editor Jules Bergman had a New York surgeon explain how a bullet could have entered Kennedy’s brain without causing any permanent impairment.

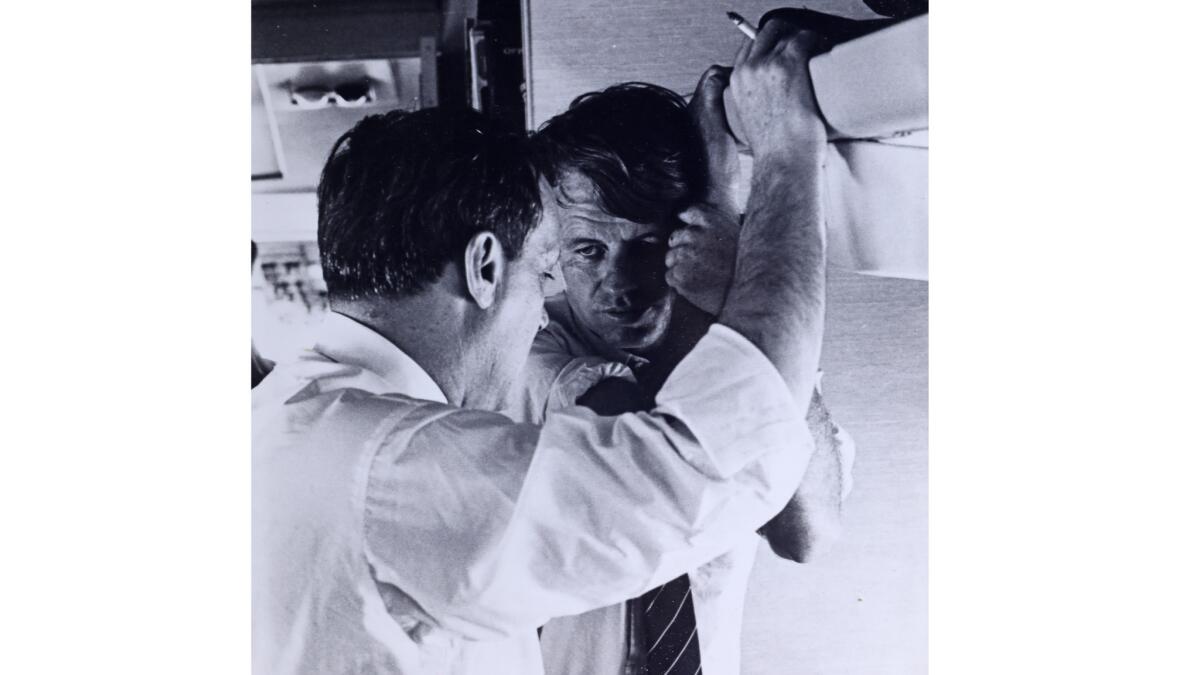

But their outlook appeared overly optimistic as the surgery, which Mankiewicz said should take 45 minutes, lasted several hours. During that time viewers saw film footage of Kennedy lying on the kitchen floor, a pair of hands cradling his head and a pool of blood underneath it. His open eyes appeared lifeless.

Faced with the prolonged live coverage of the shooting of a prominent political figure for the second time in two months, TV journalists became emotional as they filled the gaps between new information. Some called for gun control legislation and decried the influence of the National Rifle Assn. on politicians — the same arguments viewers are still hearing some 50 years later after every school shooting. They questioned how candidates would be able to campaign in public again and whether the country was headed toward a police state.

Spouting opinions and speculation — a staple of cable news — is common now, but rarely happened during the broadcast network hegemony of the 1960s, when most viewers got their information in the measured presentations of Cronkite’s evening newscast and NBC’s “The Huntley-Brinkley Report.”

“The anchors and reporters of that time tried to keep our personal views out of the story, but in those kind of instances, it slipped a lot,” Donaldson recalled.

On June 6 at 1:59 a.m., Mankiewicz appeared before TV cameras inside the hospital for his fifth and final briefing to say that Kennedy had died. Josh Mankiewicz said he knew the outcome once when he heard his father say “Senator Robert Francis Kennedy” at the start of his statement.

As often happens now during national tragedies, other TV personalities addressed the news in their own way. Johnny Carson, Kennedy’s neighbor at the United Nations Plaza in Manhattan, turned NBC’s “The Tonight Show” into a wake with the late senator’s New York friends. PBS host Fred Rogers made a special episode of “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,” in which his puppet characters talked about the assassination as a way to help children cope with the trauma. (In the weeks following the assassination, network executives instructed producers to curtail violence in their scripted shows as Washington politicians claimed TV was a cause of the real-life mayhem in society.)

Robert Kennedy, right, with his press aide, Frank Mankiewicz.

ABC, CBS and NBC pooled resources to cover the June 8 memorial service at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York and the 21-car funeral train that took Kennedy’s body south for burial at Arlington National Cemetery. TV cameras were positioned at every stop along the route, where crowds gathered in sweltering heat to watch the train pass. In Baltimore, the throngs that lined the platforms spontaneously broke out into song, alternating “We Shall Overcome” with “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

Even during the solemn procession, there was no respite from the year’s violence. Anchors broke in during the coverage with the news that James Earl Ray, a fugitive wanted for the murder of King, had been captured at London’s Heathrow Airport.

In his 2017 book “Bobby Kennedy: A Raging Spirit,” MSNBC host Chris Matthews noted how the extended journey through the bleak railroad yards lacked the majesty of the farewell President Kennedy received. “For Jack, there was the Yeatsian beauty of the rider-less horse with the boots on backwards and the beautiful Kennedy family,” he said. “For Bobby, it was that sad train ride. It was just loss.”

Frank Mankiewicz remained a Washington fixture as the manager of George McGovern’s unsuccessful 1972 presidential campaign and later, chief executive for National Public Radio. But his televised briefings seen by millions of Americans in June 1968 indelibly linked him to Kennedy’s assassination through his death in 2014.

“I think my dad would’ve given anything to not be famous for the thing that made him famous,” said Josh Mankiewicz. He noted how his father was reluctant to reflect on his grim task of 50 years ago, but there were times he could not avoid it.

“Once, I was traveling with him and we went to buy a newspaper at the airport before we got on a plane,” Mankiewicz recalled. “And the woman who sold him the paper stared at him. And we both noticed that she was staring at him. All of a sudden she said, ‘I know who you are,’ and she started to cry. My dad tried to console her. I’ve never forgotten that.”

ALSO

1968: The year in entertainment

Rage and wonder in 1968: The year war came through the TV and I felt pieces of childhood ending

‘The Mod Squad,’ ‘Adam-12’ and how TV brought the counterculture into 1968’s cop shows

Watching ‘The Smothers Brothers,’ ‘Laugh-In’ and the Democratic National Convention

The Velvet Underground, Aretha Franklin, Tiny Tim: An alternate history of music in 1968

Twitter: @SteveBattaglio

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.