Former city workers retired, but still working

- Share via

Former Glendale Police Capt. Ray Edey is not one to relax, so when he had the opportunity to return to writing grant applications for the city in September 2011, about a week after he retired, he took it.

“I don’t golf, fish or hunt,” said the 30-year employee. “I need to keep my mind busy.”

In addition to more work, he also reaped more money. He took home both an annual pension of $198,386 and a self-reported salary of roughly $80,000 a year until about four months ago.

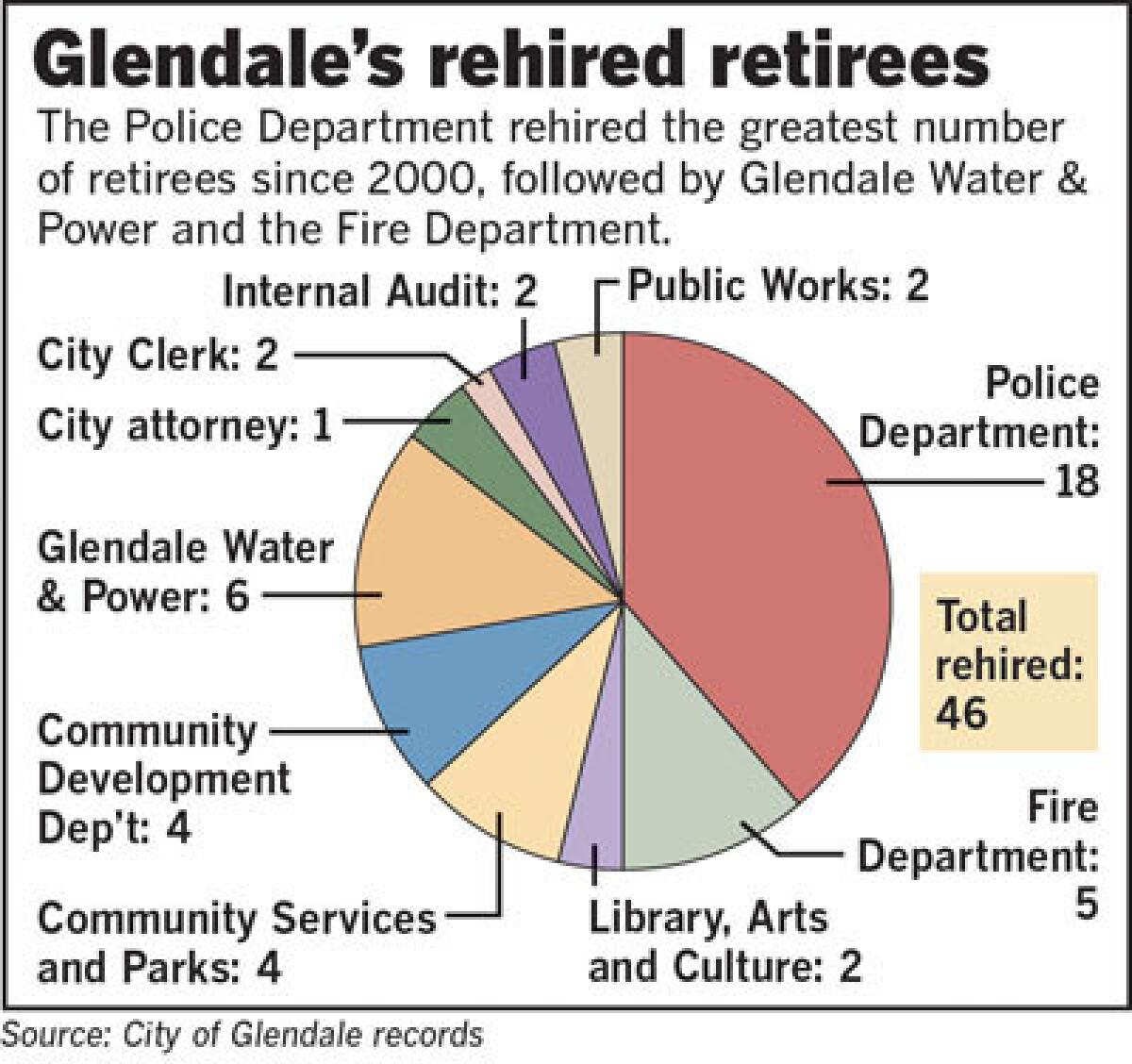

Edey is one of 46 city employees who, since 2000, retired and then returned to work at City Hall, according to an analysis of records from Glendale and California Public Employees’ Retirement System, or CalPERS.

City officials call the practice a money-saver. Critics call it “double-dipping.”

Pension reform has been in the limelight nationally as public agencies grapple with rising liabilities. While the public has been stunned by underfunded pension systems into the hundreds of millions of dollars, news of government employees collecting two paychecks has also sparked its own controversy, experts said.

“When they find out about it, they’re usually not very happy,” said Jack Dean, editor of pensiontsunami.com, a project of the conservative California Public Policy Center. “The average taxpayer assumes when you start collecting a pension, you’ve retired. If [employees] really wanted to continue working, they should continue working.”

Of the rehired Glendale retirees, 37% are from the police department, a common situation since the retirement age among public safety personnel tends to be lower than other employee groups.

But when Police Chief Ron De Pompa, who is set to make $103 an hour and collect an annual pension of roughly $192,000, hears the term double-dipping, he gets frustrated.

“People really don’t understand the system,” he said, adding that employees contribute portions of their paychecks to their pensions.

It could also take months before a newly retired employee starts collecting benefits, De Pompa added, and it’s difficult to fill high-ranking positions, such as Edey’s.

But Rosanna Westmoreland, a CalPERS spokeswoman, said the goal is to have benefits paid within 90 days of receiving a retirement application and a mixture of employee and employer contributions fund benefit checks from the beginning.

By returning to work, De Pompa said he and Edey saved the Police Department more than $40,000 that would have gone to cover the full-time benefits of their replacements. Those savings, he said, can cover overtime clocked by other employees.

“If you look at it from the city’s point of view, we do save money bringing them in part-time rather than hiring full-time,” said Councilman Ara Najarian. “If you look at it from the employee’s point of view, it’s very lucrative for them. It’s very generous compensation.”

While David Draine, senior researcher at Pew Charitable Trusts, affirmed double-dipping as an accurate term, he said it’s the system that should be criticized, not employees.

“They’re not breaking the rules, they’re following the rules,” Draine said.

Some states, such as Florida, have adopted programs that hold pension payments in a trust account — which can collect interest — if employees continue to work and draw a paycheck from the public agency. At the end of their extra service, which is limited to about five years, they can access the deferred benefits.

Part of the incentive to “double dip” is due to the retirement age being so low, experts said.

Glendale, as well as the state, has increased retirement ages in recent years. Long-time Glendale workers can retire at 55, or 50 for public safety employees. The retirement age for new hires who weren’t formerly part of CalPERS is now 62 and 55, respectively.

CalPERS has guidelines for employment after retirement, but they can be circumvented. Public safety employees and those with specialized skills are exempted from a six-month waiting period before returning.

Former city employees are also free to work at private companies. Former Glendale City Manager Jim Starbird — the city’s top pension earner at $238,686 a year — works as a principal at the city’s sales tax consultant firm. And former City Atty. Scott Howard, who draws a $191,080 annual pension, works at a downtown Los Angeles firm.

About a quarter of the rehired retirees in Glendale came back in September or October of 2012 after the city reduced its workforce to about 1,600 people through early retirements, layoffs and eliminating vacant positions. Some of them, such as John Pearson, a community services and parks project manager, were brought back on to finish projects.

Pearson was supposed to work for three months on a park project, but he’s been at City Hall for double that tying up loose ends. He can collect a maximum of $1,010 a week in addition to his $35,645 annual pension, according to city documents and CalPERS records.

“While it’s not a big financial driver of the pension challenges we’ve been seeing across the country, it doesn’t reflect what voters like seeing,” Draine, the pension researcher, said.

--

Follow Brittany Levine on Google+ and on Twitter: @brittanylevine.