First people of O.C. fight to preserve the land of their ‘mother village’

- Share via

For decades, the Juaneño Band of Mission Indians fought to preserve a sliver of the land they once called home in San Juan Capistrano.

Following several delays and political hurdles, the Native American community considered to be the first people of Orange County celebrated the opening of the Putuidem Village in December. The 1.5-acre park will serve as a place for the tribe to hold ceremonies and educate the public about the old ways.

But the fight to preserve the land of the ancient village isn’t over yet. The Putuidem Village park is only a small portion of the 65-acre Northwest Open Space, where their “mother village” once stood.

Several Native American tribal leaders and local conservation groups sent a letter to San Juan Capistrano city officials this week, urging them to preserve the land. The letter was sent ahead of a meeting on Tuesday night when the council discussed proposed developments for the Northwest Open Space.

“We are concerned that [Northwest Open Space] will end up being turned over to housing or other development not compatible with Putuidem Village Park,” the letter says. “Though we recognize the urgent need for more housing, especially affordable housing, we believe that open space and indigenous cultural sites in this area both hold a unique value that cannot be displaced or encroached upon without significantly degrading the quality of life of San Juan Capistrano’s residents and the character of our city.”

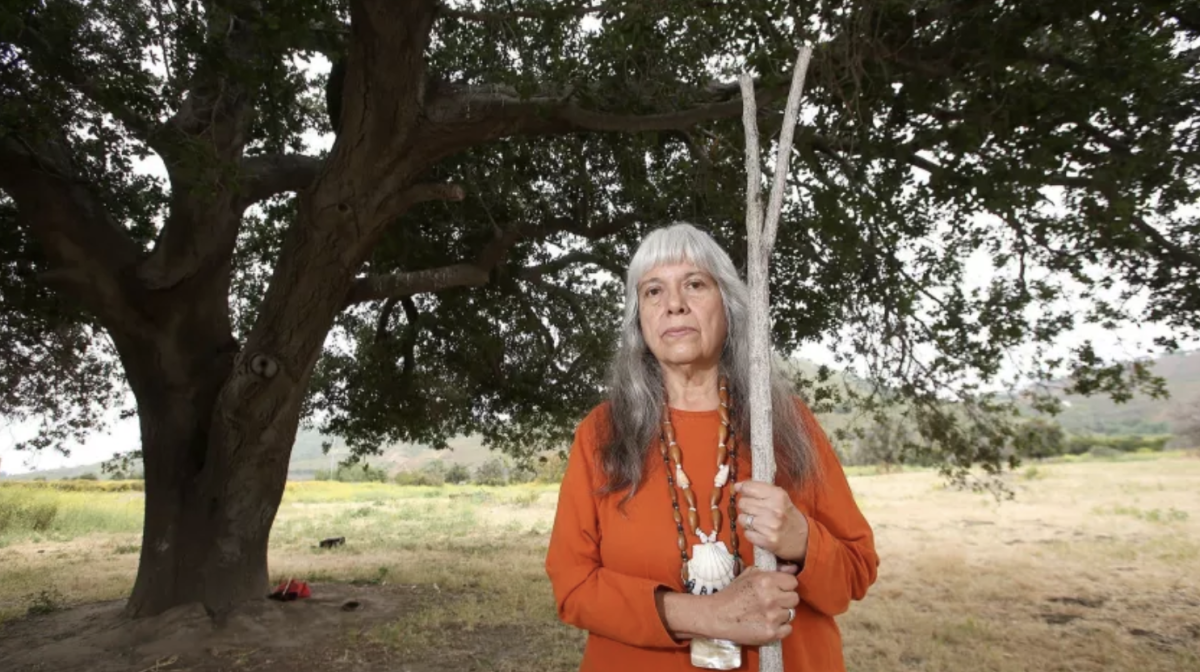

For Juaneño tribal member Rebecca Robles — who was part of the group that sent the letter, protecting the land is of the utmost importance to her people because the Acjachemen descendants, whose history traces thousands of years, have had their sacred sites and lands plundered, desecrated and devoured by development. The tribe became known as the Juaneños after Spanish colonialists built Mission San Juan Capistrano in 1776. Today, there are about 1,900 members in the tribe.

Development has been proposed on the land before. In 2019, a glamping and camping business was being considered for the Northwest Open Space, though residents opposed it, claiming at the time that the development goes against the language of Measure D, which voters passed in 1990 in order to use bond funds to “acquire lands for park, agriculture, open space, and related uses, in order to save these lands from potential residential and commercial development and to develop youth, senior and other community facilities.”

“These sites are as important to us as Rome or Mecca or a church,” Robles said. “For us as indigenous people, it’s very important for us to be able to go back to our villages and our sacred sites.”

According to a city staff report, the Northwest Open Space property has a land use designation of community park and is zoned as specific plan/precise plan, which allows various open space recreation and agricultural uses. This includes public facilities, nature study centers, farming and orchards, picnic areas, equestrian facilities, wineries and event venues.

At the Tuesday council meeting, several people who backed the letter spoke out in support of protecting the land from any development. Organizations that signed onto the letter include Banning Ranch Conservancy, Preserve Orange County, Save Laguna Canyon, California Cultural Resource Preservation Alliance, Endangered Habitats League, United Coalition to Protect Panhe, Saddleback Canyons Conservancy and Friends of Harbors, Beaches, and Parks, among others.

After hearing the opposition, council members voted to move forward with issuing the request for proposals to a specific list of businesses for the future use of the Northwest Open Space. They also modified the item to allow community members to submit ideas to the city.

Among the businesses that have expressed interest in the area in the past and will receive the request are an ecology center, vineyard, event and wedding venue and a barbecue restaurant. Businesses the city chooses will be invited to a public workshop in the spring, when they can present their concepts to the council and community.

Council members mentioned that the developments won’t be intrusive or encroach on the Putuidem Village.

“I have a strong desire to protect the space from any sort of intrusive developments such as housing and businesses,” said Mayor Pro Tem Howard Hart. “My goal is to preserve this valuable piece of land in a manner that balances both the Acjachemen heritage and the non-Acjachemen heritage, as well as the future of San Juan Capistrano.”

Councilman Troy Bourne said that people in opposition to development seemed to be misunderstanding the city’s intentions in seeking out proposals for the Northwest Open Space.

“Staff is coming in saying we’re looking at proposals that would be consistent with the current land use designations that are out there — nobody’s proposing apartment complexes, shopping centers, etc.,” Bourne said.

Robles said developments surrounding the Putuidem Village would diminish the ambience of the cultural park. The park was built, in part, as a place for the Juaneño to carry out important cultural ceremonies and rituals.

“It is our mother village,” Robles said of the original village. “There’s so much of our history there. It’s very important for us to continue to protect it ... Much has been destroyed, which makes it even more important for us to preserve this portion of California history.”

Patricia Martz, a former Cal State Los Angeles anthropology and archaeology professor who was part of the group that sent the letter, echoed Robles’ sentiments and said development would ruin the cultural demonstrations held at the Putuidem Village park.

“Finally after eight years of coming before the City Council and begging, we finally got them to construct that interpretive park,” Martz said. “For them to lease it out to development is just very concerning.”

With much of Orange County being developed, Robles contends that it’s more important than ever to defend the minimal amount of open space that is left.

According to the California Cultural Resources Preservation Alliance, at least 90 percent of the known archaeological sites that once existed in Orange County have been replaced by development. Native American sites have been paved over.

In 2008, archaeologists uncovered 174 sets of human remains from a site of a housing development that was under construction in Huntington Beach. A few years before that, JSerra Catholic High School was built over what was once the core area of the original Putuidem Village, Robles said.

“It’s a valuable and essential resource for the residents of San Juan Capistrano,” Robles said. “Our ability to go back to nature is very connected to mental health, spiritual health and physical health. That’s something that’s crucial in these very trying times.”

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.