O.C.’s iconic piers, with their colorful pasts, help define their cities

- Share via

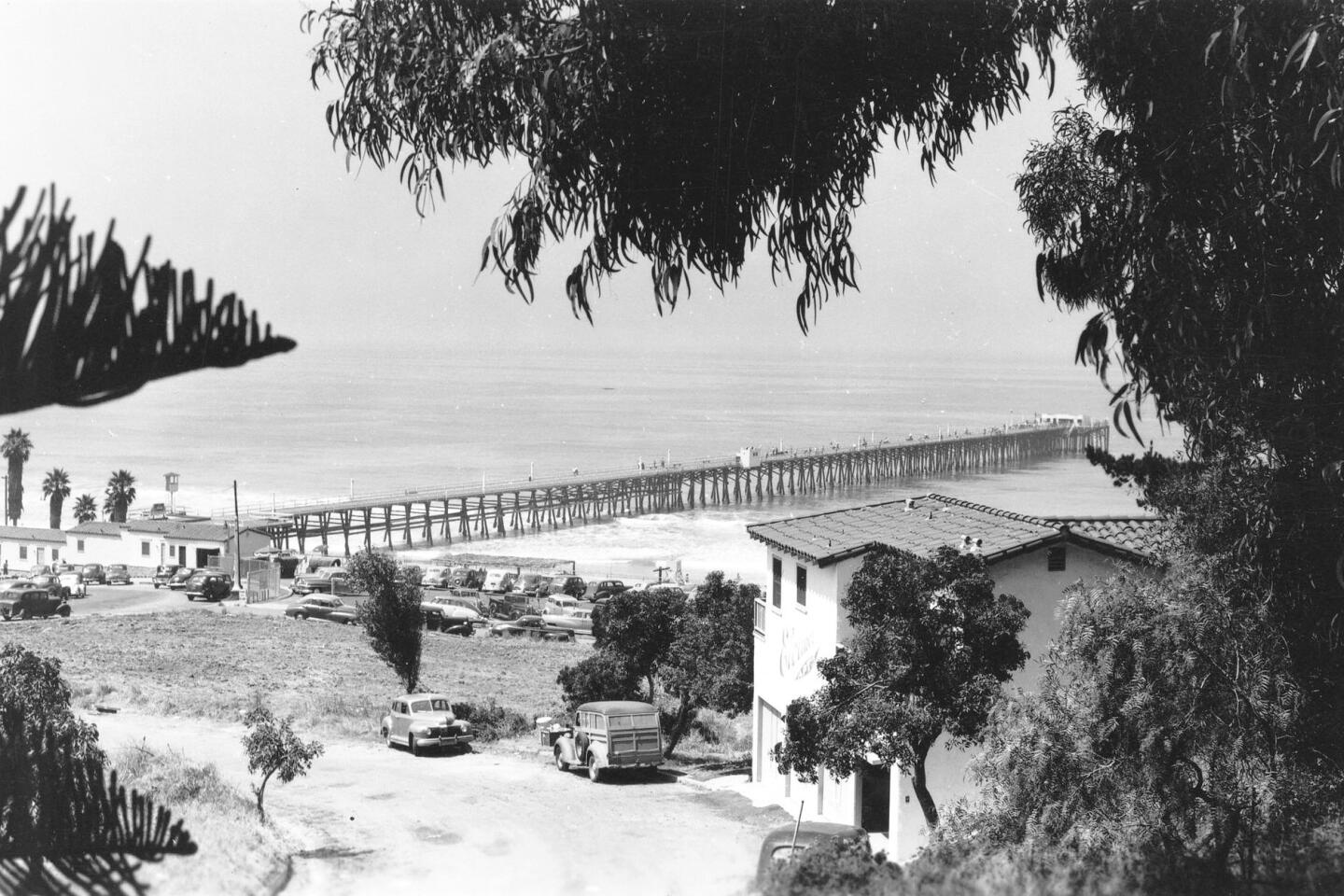

Jack Lashbrook has spent much of his life on the San Clemente pier.

The 90-year-old got his first glimpse of the structure as an 11-year-old boy after his parents relocated the family from Illinois to San Clemente.

He recalls looking out at the Pacific and being mesmerized by the way the waves crashed against the wooden structure, creating frothy white foam that traveled up the sand.

“I’d never seen anything like it before,” he said. “It was quite a lot of fun.”

Between helping his parents in the restaurant they owned at the end of the pier to meeting his wife, Doris, the historic spot has been the setting of several special moments for the longtime San Clemente resident.

And he’s not alone.

Each day, regardless of the weather, families and couples, tourists and fisherman can be found strolling along Orange County’s five piers, which include, north from San Clemente, the Balboa and Newport piers in Newport Beach as well as those in Huntington Beach and Seal Beach.

The piers, like their coastal city homes, each has an individual identity and flair. The piers not only reflect the millions of people who visit them each year, like Lashbrook, but also the history of the cities that take care to preserve the iconic structures, especially during winter storms — like the current El Niño season.

All five structures have suffered damage to some degree since their construction decades ago. And each time, the cities have stepped up to rebuild. During tough financial times, each city has in essence pondered: What would we be without our pier?

“I can’t even imagine the city without its piers,” said Steve Rosansky, Newport Beach Chamber of Commerce president and former councilman. “It brings tourists and residents to the waterfront and serves as an anchor for all types of activities in the community.”

And so the decision to repair is made.

“The piers are part of the personality of these communities,” said historian and Orange County Historical Society President Chris Jepsen. “The towns have grown up around them. They’re part of the package deal.”

While the piers today offer places to relax and view a sunset, eat dinner while enjoying an ocean view and just get lost in the immensity of the Pacific, their origins tell a different story, about a time when a bustling maritime industry was key to commerce in the area.

Orange County’s piers largely began as wharfs where steam boats could tie up and unload goods. This was before shipping lines were replaced by railroads and other ground transportation.

Other uses would be found for the piers before they would transition into their current status as relaxation spots and tourist draws.

Some of these uses were illegal.

But it’s all part of coastal Orange County’s colorful history.

*

Shipping hubs

Newport Pier, the oldest of Orange County’s piers, was originally called McFadden Wharf. It was built in 1888 by brothers James and Robert McFadden, local shipping tycoons, as a means to offload lumber and other goods from vessels that were stopping in Newport Beach.

Railroad tracks extended to the end of the structure, aiding the McFaddens in transferring lumber and other merchandise from the ships. The products would then be sent via rail to the surrounding areas.

The piers in Seal Beach, San Clemente and Huntington Beach operated in the same way at their inception.

But Prohibition opened another chapter.

In the 1920s, Seal Beach became a hub for rum running, a place where locals could skirt Prohibition laws away from the watchful eyes of police, who were located in central Orange County.

“If you wanted to set up marginally legal and illegal operations at the time, it was the perfect place to do it,” Jepsen said.

Historians say the Seal Beach and San Clemente piers became cornerstones of a sort for questionable activities, providing landing places for boats dropping off illegal merchandise and serving as settings for illegal gambling during the early part of the 19th century.

“A lot of those piers had landings for boats,” Jepsen said. “We don’t think of that now because all of it has turned into fishing. We don’t think of the piers as being functional in other ways.”

*

First residents, then tourists

The history of the structures is not only connected to shipping but also the arrival of the Red Car system of mass transit. Balboa, Newport and Huntington piers were built to coincide with developer and railroad magnate Henry Huntington’s trolley line, which brought vistors south from Los Angeles.

Early developers in Orange County, including Huntington and later Ole Hanson, who oversaw the building of the youngest of the county’s piers — in San Clemente in the late 1920s — envisioned the structures as a way to attract new residents to their seaside towns.

Huntington also built a pavilion for dancing and a hotel nearby to attract people to what is now known as Huntington Beach, nicknamed Surf City.

The wooden Seal Beach pier was built in 1906, at the same time developer Philip Stanton was promoting Bay City, which would eventually be renamed Seal Beach. Less than 10 years later, the pier was rebuilt and became the setting for the Joy Zone, an amusement park with rides, a dance hall, carnival games and the well-known scintillator light show, which some say could be seen up to 12 miles away.

“It was part of creating a community and a center location for the community to build around,” Jepsen said.

Developer William S. Collins had a similar vision for Newport decades earlier. After the McFaddens sold the site of the Newport Pier in 1902, Collins decided to transform the area for residential and recreational purposes. In 1906, the Balboa Pavilion and its sister project, the Balboa Pier, were constructed with the intent of attracting new home buyers to the area.

The piers’ ability to bring people to the seaside communities has withstood more than 100 years. The history of fishing as a recreational activity on the piers has also survived.

The Dory Fleet market, which sits at the base of the now roughly 1,300-foot-long Newport Pier, pays homage to the city’s long commercial fishing history, which developed in the 1890s. Today, the salty smell of mackerel mixed with sea water overwhelms the senses as recreational fishermen extend their lines off the ends of the Newport and Balboa piers even before the rising sun has peeked over the shoreline.

*

El Nino storms and repairs

The structures, with their rich history and aging infrastructure, have nearly all been completely rebuilt since they were originally erected. Some repairs were the result of normal ocean abuse and wear and tear, while other fixes resulted from violent El Niño storms that battered the coastline beginning in the late 1930s.

“It’s a battle against nature,” Jepsen said. “Out of all the piers in Orange County, it’s a pretty safe bet that none of them have any original parts.”

Lashbrook, who is now the city patriarch, recalls standing on the sand in San Clemente in the winter of 1939 — just two years after the Lashbrook family got its start in the Spanish village by the sea — to watch as a powerful storm demolished the original pier.

Lashbrook and his friends watched from the sand as waves from a powerful storm ripped through the pier’s middle section.

“The waves would hit the side, wash over the top and knock the benches all the way across the pier,” he said. “Me and some of my buddies stood and watched it sway.”

The ocean water churned and another set of violent waves hurled forward once more to claim the end of the wooden structure, leaving nothing but a short bit at the base. By the end of the storm, pilings and other debris had traveled as far north as Dana Point.

The Newport Pier also suffered significant damage in the storm and was later rebuilt.

Unbeknown to Lashbrook at the time, the teen was witnessing his first El Niño-powered storm. Such storms are caused by a warming of the equatorial waters of the Pacific, which results in heavy rain in California. Back then, he said, they just called it rain and big waves.

The San Clemente pier was rebuilt in the early 1940s, but the couple who had previously operated the restaurant at the end of the structure were not interested in starting up their business again. So, the Lashbrooks became restaurateurs, feeding fisherman and locals at the pier until the 1950s.

The restaurant business was booming from the constant stream of customers who would stop in for breakfast before heading out for the day on a fishing boat docked at the end of the pier.

“It would be 4 a.m. and I would be at home in bed and get a call to get down there to help,” Lashbrook said.

Orange County piers would face another series of large El Niño storms in the 1980s, resulting in nearly all undergoing repairs or rebuilds.

*

Preparing for the worst

Some cities, like San Clemente, made their piers stronger and in hopes that they would be more likely to withstand damage from future El Niños. Forecasters expect this El Niño season to be the most powerful on record.

So far, city officials’ wishes have come true. The first series of winter storms last week, which brought powerful surf and dumped several inches of rain across the county, did not cause any reported damage to the piers.

San Clemente, like many municipalities, has inspected the condition of its pier and made improvements to structural components, according to Bill Cameron, public works director and city engineer.

This winter, the city will spend roughly $138,000 to inspect the structural integrity of the 1,300-foot pier. It’s an expenditure that the city takes on roughly every five years to prepare for repairs, which could begin in early 2017, according to city documents.

“Overall, our pier is in good condition and should be able to withstand most any storm and surf conditions, unless they are much worse than what has been experienced over the past 29 years that I have been working for the city,” Cameron said. “This includes two or three El Niño winters and heavy surf.”

Up the coast, Newport Beach inspects and repairs its piers every two years, replacing worn out beams and rusted joints and metal fittings and checking the integrity of the piles.

Maintaining a pier is a labor of love — as well as a matter of significant cost — for most cities. Local governments can spend anywhere from several hundred thousand dollars to more than $1 million on repairs every few years, according to officials.

“They take quite a beating out there,” Webb said. “We try to stay on top of the work as best we can.”

Orange County might well have been able to claim more than five of the iconic landmarks, but some piers didn’t survive.

Laguna Beach once had the Aliso Beach Pier. The county demolished the diamond-shaped object, which was built in 1971 from concrete and steel as part of a public beach development, in 1998 after the county Board of Supervisors declared it irreparable following El Niño storms the previous winter.

The Capistrano Beach pier, a T-shaped wood structure built in 1929, acted as a hub for fishing. Decades later, the pier had fallen into disrepair, and in a spectacular show in 1965, officials removed it with explosives.

*

What does the future hold?

The future of each of Orange County’s piers — and how their identities will be shaped in the coming decades — has yet to be decided. Newport and Seal Beach are currently struggling to determine how best to upgrade the aging buildings at the ends of their piers.

Newport Pier Grill and Sushi made a home on the Newport Pier most recently, from 1993 until 2012, when its lease with the city ended. In recent years, the now-dilapidated building has remained vacant.

The wood structure has extensive dry rot and water damage. Inside, the electrical system doesn’t work, and the once-bustling kitchen is out of commission. The City Council has not yet decided how it plans to go about rehabilitating the city-owned structure, but council members have indicated their support for hosting another restaurant on the pier.

In Seal Beach, the pier-end restaurant building, once home to Ruby’s Diner, remains vacant and continues deteriorating. While city leaders have been vocal in their support for a new restaurant at the site, the cost of fixing the pier to accommodate a restaurant would cost Seal Beach more than $3 million, according to city documents.

Until the City Council moves forward, the far end of the pier remains chained off, blocked from public access.

Still, many seaside cities haven’t given up on their precious coastal structures, as they weigh public enjoyment and the money tourists bring in.

“You get a different perspective of the city from out on the pier,” Webb said. “There’s something peaceful and charming about being over the waves.”

*

ORANGE COUNTY’S PIERS:

San Clemente Pier

Date built: 1928

Material: wood

Current Length: 1,296 feet

Restaurants: The Fishermans Restaurant and Bar, located at the base of the pier

*

Balboa Pier

Date built: 1906

Material: wood

Current Length: 920 feet

Restaurants: The original Ruby’s Diner opened here in 1982.

*

Newport Pier

Date built: 1888

Material: wood

Current Length: 1,322 feet

Restaurants: currently none

*

Huntington Beach Pier

Date built: 1904

Material: concrete

Current Length: 1,856 feet

Restaurants/Attractions: Ruby’s Diner, Kite Connection

*

Seal Beach Pier

Date built: 1906

Material used: wood

Current Length: 1,835 feet

Restaurants: vacant, previously housed a Ruby’s Diner

*

ALSO:

Silverado Canyon dwellers hunker down as storms threaten hillsides