Glendale pays big pension numbers

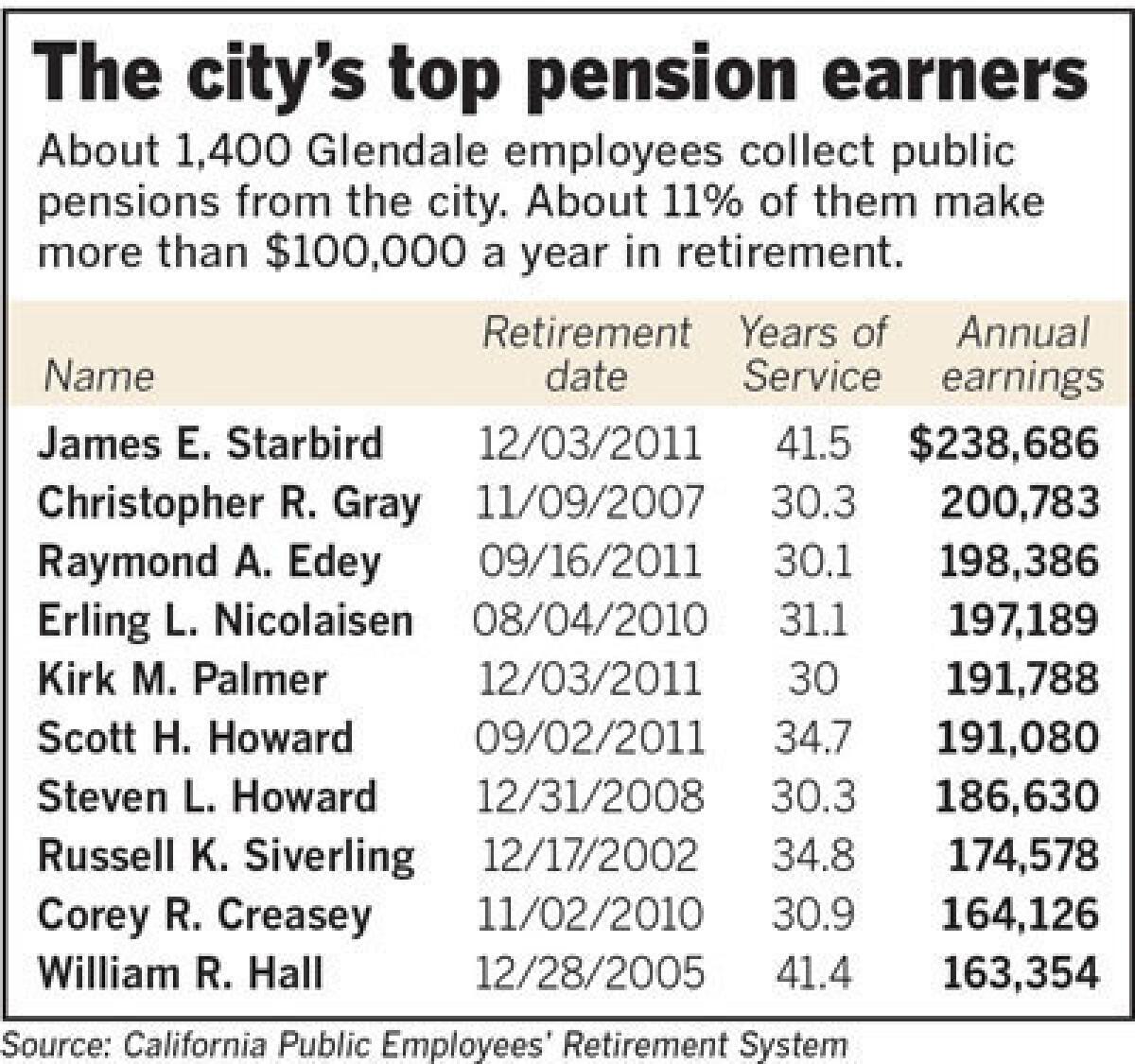

As Glendale struggles to get a handle on its growing pension obligations, records show that about 11% of the nearly 1,350 city retirees draw annual pensions of more than $100,000 a year — and some of them far more than that.

At the top of the list is former City Manager Jim Starbird, who draws $238,686, followed by ex-Fire Chief Christopher Gray at $200,783 and former Police Capt. Ray Edey at $198,386.

But the sticker shock of high earners doesn’t tell the whole story, pension experts said. The average is often much lower than the top earners, including in Glendale.

According to an analysis of data from the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, or CalPERS, municipal retirees from Glendale draw an average annual pension of $50,654 — nearly twice as much as their counterparts nationwide. But most retirees, or 38%, make between $10,000 and $39,000 annually. About 27% collect between $40,000 and $69,000, the data shows.

Despite steps taken in recent years to reduce benefits for new hires, Glendale is grappling with rising pension costs. Retirees are not only living longer, but many long-time workers benefited from guaranteed increased pensions approved nearly 13 years ago. That means the new changes, including a statewide cap on how much of one’s salary is used to calculate a pension, may not have significant impacts for decades to come.

In addition, CalPERS rates charged to cities are set to increase in 2015, which could add an extra $10 million to $15 million to Glendale’s pension bill, which grows every year.

Last year, Glendale’s annual pension cost was about $30.6 million, but the city also has an unfunded liability — the difference between the assets it has and the cost of the promised benefits — of about $227 million.

What’s more, the pension debate, in Glendale and nationally, has been exacerbated by the protracted recession. As the still-recovering economy continues to exert downward pressure on the retirements of private-sector citizens, empathy for public workers has waned, experts say.

“There’s a lot of this sense of pension envy,” said Diane Oakley, executive director of the National Institute on Retirement Security.

According to a study released in March by the research center, 82% of 800 respondents said all employees should have similar benefits as public employees.

But those guaranteed benefits, no matter the market conditions, are rare in the private marketplace. About 14% of all private-sector workers in 2011 could access that kind of pension, down from 38% in 1979, according to the Employee Benefit Research Institute.

That’s partially due to onerous federal rules on private-sector defined-benefit plans, which tend to push employers instead toward defined contribution plans, such as 401(k)s, experts said. The same rules don’t apply to CalPERS.

Still, many city officials say the private sector has it better off when it comes to retirement benefits — but private workers say the same about their government counterparts.

From the security perspective, government employees are better off than their private counterparts. When it comes to the ability to get big bonuses, it’s the opposite.

“You’re always going to find the argument is ‘Oh, poor me,’” Richard Garcia, a human resource management consultant and adjunct associate professor at USC said. “Public employees have been guaranteed an income based on long-term employment, not based on performance, like in the private sector.”

Councilman Frank Quintero said while retirement benefits can be reviewed going forward, changes can’t be retroactive.

“This is what they bargained for over years,” Quintero said. “There’s nothing you can do.”

There’s no data to compare a defined benefit output to that of 401(k) plans because the former is public information, unlike the latter, experts said. The Employee Benefit Research Institute tracks average 401(k) account balances, but that shows current accruals, not post-retirement draw-downs, which can be impacted by turbulent markets, employment length or other factors.

The average 401(k) account balance in 2011 of 24 million workers analyzed by the non-partisan institute was $58,991, but that was heavily buoyed by those making more than $250,000. The midpoint was $16,649.

Then there are the six million Californians that have no retirement plans whatsoever.

“In reality, that’s where the real problem is,” Oakley said.

--

Follow Brittany Levine on Google+ and on Twitter: @brittanylevine.