Learning Matters: While today’s students basically remain the same, influences around them have changed

- Share via

“Kids haven’t changed. A lot has changed around them.” So said high school math teacher Sarah Morrison when I sat down with her and her colleague Aurora Alamillo to discuss teaching practices and their relation to student writing skills.

Morrison is one of several teachers I emailed to get information and perspective on the concerns expressed by Hoover High English teacher — and my Glendale News-Press column colleague — Brian Crosby in his recent column on the topic. (“Writing skills continue to decline in schools,” Jan. 25, 2020.)

As I wrote in an email to Crosby, his column prompted questions for me, as I suspect it did for other readers.

“Imagine how much stronger [student writing] skills would be if they were practicing them in history and science classes,” he wrote, causing me to wonder if the district still emphasized “writing across the curriculum.”

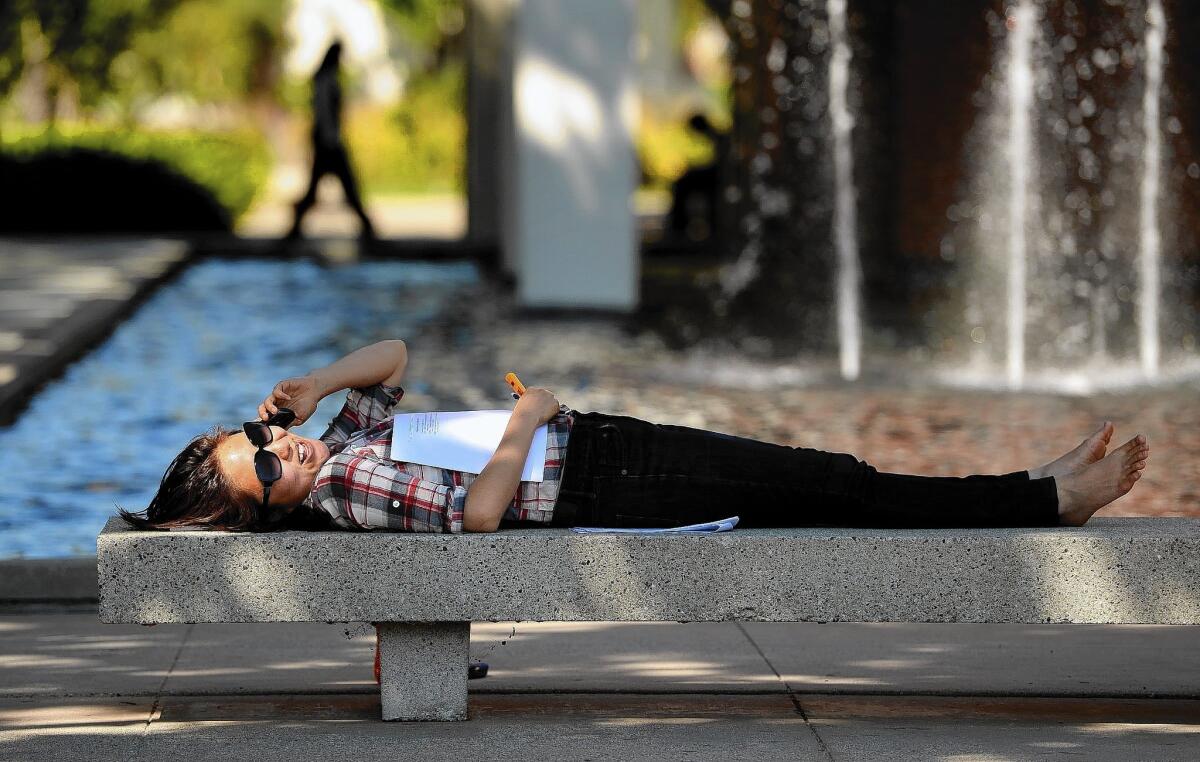

His column touched on the ubiquity of cellphones, and I wondered about the effects of screen time, and what behaviors other teachers are seeing.

I know that our daughter, an elementary principal in Milwaukee, has concerns about the developmental effects on young children who spend so much time on phones and tablets.

Plenty of parents here worry about their teen’s time on social media.

As a longtime advocate for both liberal arts education and career education, I also couldn’t help but wonder whether visions of entrepreneurial riches, like developing a computer application at the age of 22 and selling it to the highest bidder, or becoming a star, such as winning five Grammys at age 18, might be getting in the way of writing and understanding.

But that’s a topic for another day.

It didn’t take long for responses to my questions to start arriving in my inbox.

Mary Mason, the district’s director of elementary education, quickly forwarded my questions to Chris Coulter, the district’s director of teaching and learning.

Commenting on the most recent districtwide writing scores, which showed a slight drop from 2018 to 2019, Coulter pointed out the bigger trends since the introduction of the Common Core State Standards a few years ago.

“Students now have to write coherent arguments and cite evidence from multiple sources to back up their claims,” Coulter wrote in an email.

“The type of text students are reading and responding to on state tests are often science and social-science topics,” he added.

He answered that many schools still emphasize writing across the curriculum.

I heard from two teachers whose students do write daily — an elementary teacher and a high school history teacher.

“I can’t speak for my colleagues,” the history teacher wrote, “but I do believe that many have their students write on a regular basis.”

His advanced-placement students “are constantly writing various forms of responses, from short answers to document essays to long essays,” structured according to the college board rubrics.

Elementary teacher Taleen Petrossians emailed me her opinion that “reading and writing go hand in hand.”

In their writing folders, her students write daily about whatever interests them.

“When it comes to giving them a topic to write about, they do well, naturally,” she said.

But, she added, “Students have their heads in technology way too often... If they were reading online that would be wonderful. But I think it’s more about game playing.”

AP English teacher Holly Ciotti concurred with Petrossians’ dismay about student reading. “Kids don’t read,” she told me as we sat in her class this week.

“They read what they’re assigned,” but little more, she said.

And when it comes to high school-level writing skills, Ciotti said, “Doing more writing doesn’t improve writing. Doing more writing with writing instruction improves writing.”

Nor is she too optimistic about the improvement promised by Common Core. “I haven’t seen it,” she said.

However, Ciotti said she remains passionate about the importance of writing, pointing to a quote by George Orwell on her bulletin board.

The quote reads, “If you cannot write well, you cannot think well. If you cannot think well, someone else will do your thinking for you.”

Math teachers Morrison and Alamillo expressed more hope about student progress with the Common Core. They spoke about the math standards that students are expected to use and the “Effective Mathematics Teaching Practices,” which guide their Common Core instruction.

They spoke about how the practices come to life in their classrooms — practices like promoting problem solving and facilitating meaningful mathematical discourse to build shared understanding.

“Students are taught to use tools to approach a problem and to develop resiliency in their struggles to learn,” Morrison said, adding that both students and teachers are working collaboratively.

“We can’t just close our doors anymore… [Students] learn through discourse, and we’re modeling that,” she said.

Both Morrison and Alamillo said they see more students engaged in critical thinking.

“They like learning,” Morrison said. “They’re interested in the content,” and they’re also developing a sense of community as they talk through the math problems. “We’re getting to know the kids,” Morrison said. “And they need it. They need the assurance of contact with adults.”

That’s where “a lot has changed around them” came back into the conversation with Morrison and Alamillo. They and others who emailed me echoed what Crosby wrote in an email: “How can we expect young people to concentrate when every time a notification beeps or hums, it’s a signal to stop everything and check the phone?”

Morrison lamented the pressures students feel, the competitive nature of their lives.

“Students experiencing unrelenting pressure is more noticeable now… even pressure to be nice,” she said.

The questions require more than my allotted space allows, so I’ll close by expressing my thanks for the effective teachers I know who, instinctively or not, follow the eighth effective teaching practice, according to “Effective Mathematics Teaching Practices,” — “adjusting instruction continually in ways that support and extend learning.”

For my part, I’ll concentrate on the fifth effective practice, appropriate for all disciplines — posing purposeful questions.