Employees protest outside 2 hospitals; union members authorize potential strike at St. Joe’s

Dozens of nurses and healthcare employees picketed outside two area hospitals this week, making various workplace demands as the end of their contracts looms.

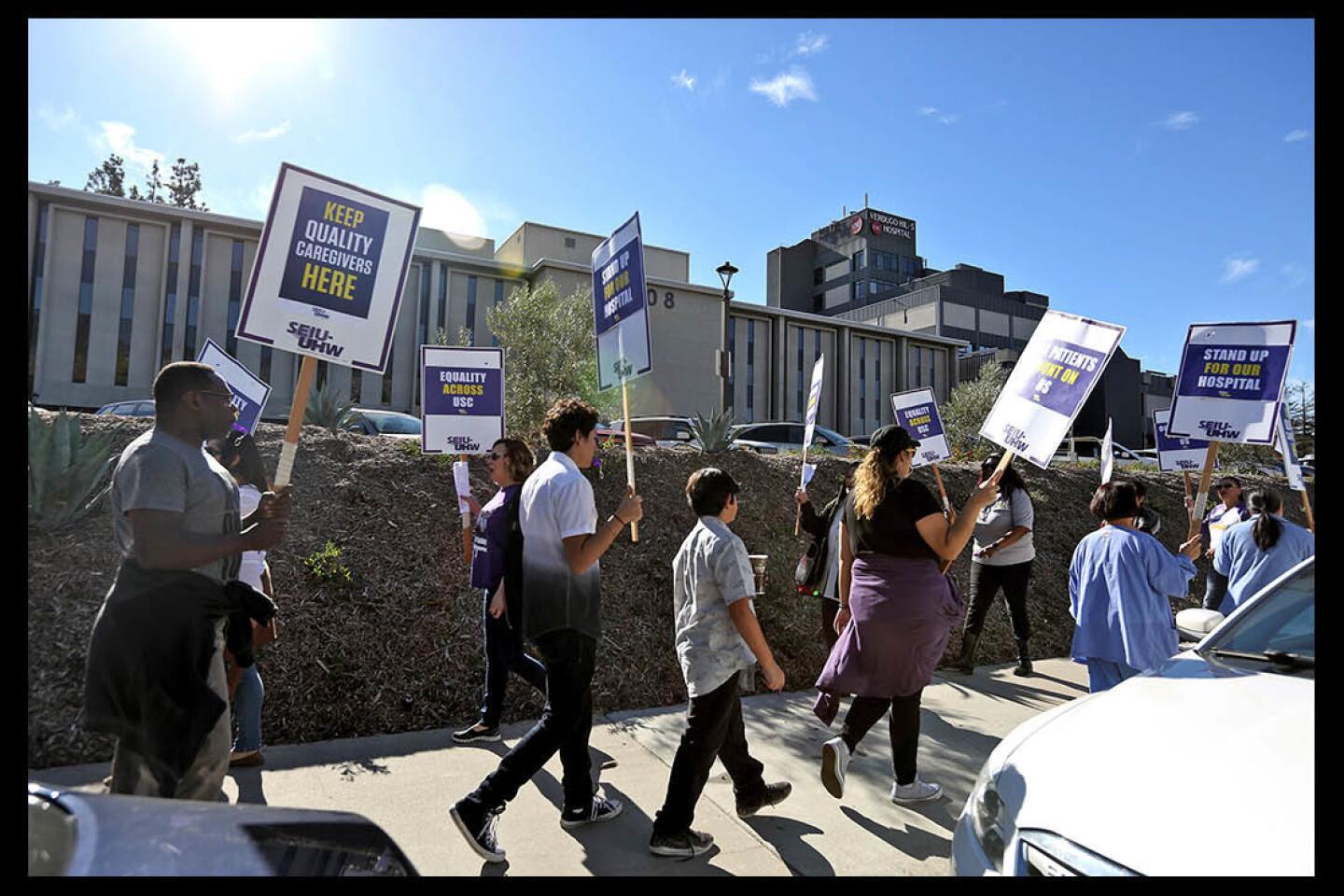

“No contract, no peace,” chanted several dozen healthcare employees and their union representatives outside USC Verdugo Hills Hospital in Glendale Wednesday, their voices slicing through an otherwise quiet morning.

Picketers claimed hospital management officials have been dragging their feet during negotiations for a proposed contract that includes employees’ requests for increases in pay and staffing, as well as free healthcare, for workers represented by Service Employees International Union-United Healthcare Workers West, known as SEIU-UHW.

“Everything has just been pushed back. We presented our proposal, but they haven’t responded to anything,” said Carlos Martinez, a nursing assistant who has worked at the hospital for seven years.

A bargaining meeting held the day before the picket did not result in meaningful progress, and no firm follow-up date has been set, Martinez said.

The existing contract is set to expire Jan. 31.

If the agreement continues to stall, Martinez said there would likely be additional picketing and even a potential strike.

Hospital management, including Chief Executive Keith Hobbs, declined to comment through a spokesperson.

Meanwhile, as workers marched and bullhorns blared outside the hospital, surgical buyer Andrew Brown held a simultaneous anti-union gathering in one of the hospital’s conference rooms.

Since October, Brown has been fighting to dissolve the union formed three years ago, when he filed a petition that was rejected by the National Labor Relations Board, or NLRB, because it arrived two days too late.

According to Brown, he has the support of a majority of the 230 workers in the bargaining unit, which includes patient services representatives, obstetrics technicians and phlebotomists.

He plans to resubmit a petition on Jan. 2 — the earliest date he can.

“What the union was telling us was lies ... and the majority of the people in the unit have realized that,” said Brown, referring to what he said was an unfulfilled promise by union leaders to secure 5% pay raises.

Grisell Rodriguez, who is leading SEIU’s field campaign for the contract, said hospital management promised employees the same raise if they voted to dissolve the union.

“If an employer wanted to give a 5% raise, they wouldn’t be stalling on the proposal that we gave,” Rodriguez said.

Pointing out that a decertification petition requires only 30% of a bargaining unit’s support to file, Rodriguez also dismissed Brown’s claim to have a majority of workers behind him.

Over the course of the contentious battle that has been playing out between pro- and anti-union forces at the hospital since Brown filed his petition, Hobbs has said several times that he supports all employees, whether they want representation or not.

Having inherited a financially failing hospital in January 2016, Hobbs in October said the morale was low all around the medical facility.

He previously said he’s helped instill a cultural and financial shift by cultivating personal relationships and introducing meritocratic raises.

Now “they feel they have enough trust in leadership that they don’t need a third party to represent them anymore,” Hobbs said after Brown filed the decertification petition.

On Wednesday, Martinez denied having that type of relationship with the relatively new management.

“When it comes to my living, and they’re not willing to help me improve that, when I come here and work hard for them, it makes it hard to really trust them,” Martinez said.

The biggest sticking point is low staffing levels, which some of the workers think jeopardizes their safety and the safety of patients, Martinez said, adding that, in particular, there is a need for more personnel in psychiatric units.

“When someone is taking care of three patients, as opposed to one, that’s a safety-hazard concern,” Rodriguez said.

No employees showed up at Brown’s lunchtime meeting, which he attributed to a combination of the union’s bullying tactics and the fact that it was difficult for employees to take time off from work.

About 100 employees signed up to take turns marching during the two-hour picket, according to Martinez. Roughly 40 people were marching at any given time.

David Acosta, a consultant not employed by the hospital and the only attendee at Brown’s meeting, questioned whether the majority of the marchers were hospital employees, suggesting they could be union employees or paid protesters.

In Burbank, numerous vehicles driving past the hospital on Thursday honked in support of the nurses and members from SEIU Local 121RN, which is the St. Joe’s chapter, as picketers chanted “Safe staffing saves lives.”

Labor negotiations were being conducted that day, with both sides trying to come to an agreement before the end of the year, when the current contract expires.

In addition to the protest held outside the hospital, the union held a strike vote, which garnered about 98% support from the nearly 900 members that voted on Thursday. That vote authorizes the bargaining team to call a strike, said Terry Carter, a spokeswoman for SEIU Local 121RN.

“Providence St. Joseph respects employees’ rights to participate in union activities but much prefers meeting at the bargaining table to reach agreements that meet the needs of employees, the hospital and the community,” officials from St. Joe’s said in a statement. “Our goal is to settle this contract as soon as possible and in a way that allows the hospital to continue providing safe, excellent and compassionate care to our patients and their families.”

Mario Isaac Cardenas Soriano, a third-year orthopedic vascular nurse, was one of the many that walked along Alameda Avenue with a sign in his hand.

Soriano had worked his way up from being a certified nursing assistant, or CNA, to a registered nurse, saying he loves working at Providence St. Joseph.

He said that this year’s flu season has not been as bad as previous years, but the workload he and his colleagues are given has reached a point where it could negatively affect patients.

“We have three [certified nursing assistants] on our floor, but we’d love to have more,” Soriano said. “I can’t tell you how often I get a patient that says they’re too embarrassed to wet the bed and tries to get out of bed on their own. I’ve seen too many falls happen for that exact reason.”

He added patients sometimes refuse to drink liquids because they assume the nurses and CNAs cannot help them in time.

For Soriano, he wants the management to understand the nurses at St. Joe’s need an appropriately sized support staff to assist them with patients.

“I’m not above anything. I’ll do whatever I need to do to help the patients,” he said. “I was an aide at one point in time, so I know exactly how difficult that job is when you have nine to 15 patients that you single-handedly have to look after, but this is crazy. We definitely need a lot more staff.”

Staffing levels for certified nursing assistants at St. Joe’s has been an issue since July, when the hospital opted to change the model to allow three CNAs for every 30 patients.

After pushback from the nurses and the union, management reverted back to the previous staffing model of three CNAs for every 24 patients, said Gity Khazan, a nurse from the neuro-cardiac unit of Providence St. Joseph.

However, she said the hospital has been moving toward changing the CNA-to-patient ratio again, and she and her colleagues don’t want that to happen again.

Khazan, who has been a nurse at St. Joe’s for 11 years, said her breaking point with management occurred when she had to take care of four patients who were in critical condition and only had the help of two CNAs.

She said those patients needed to be turned to prevent bedsores from occurring, but because she was shorthanded, one of those patients ended up developing those sores.

“We’re hoping we can negotiate terms that will really benefit the patients,” Khazan said. “That means that we need adequate staffing and resources to take care of our patients.”