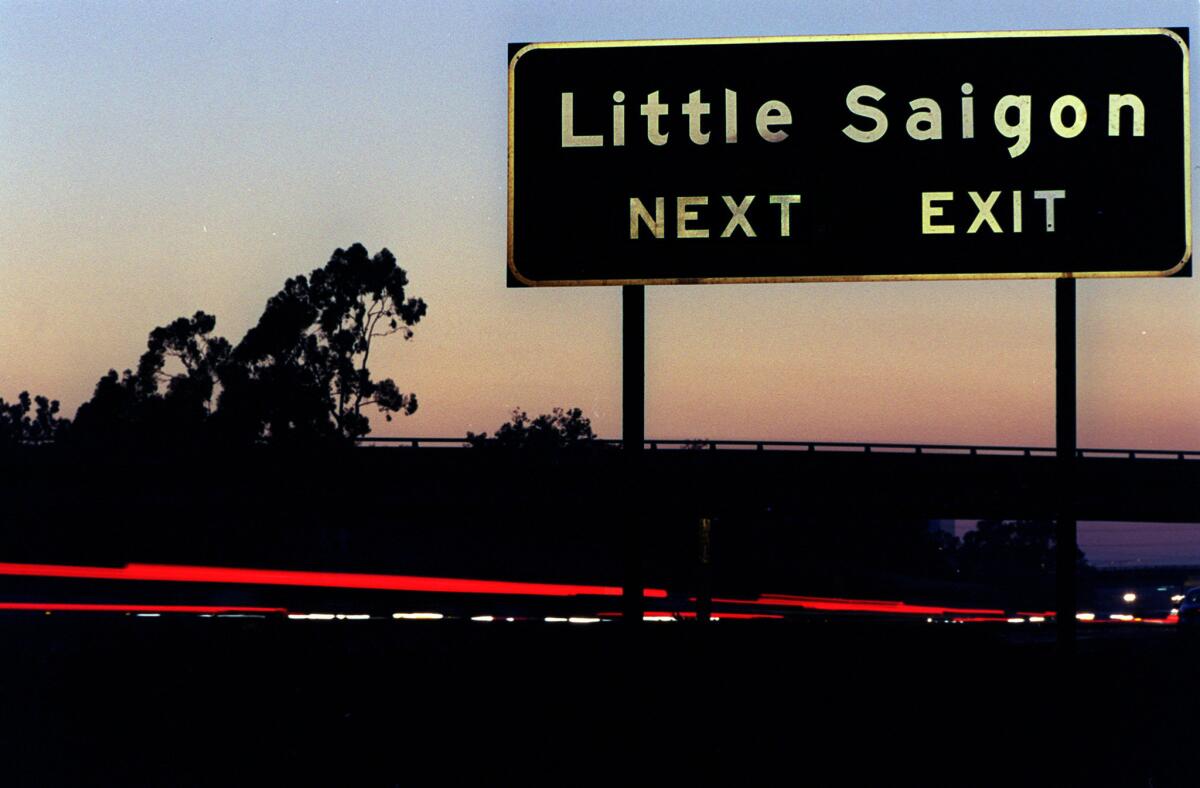

Susan Lieu’s one-woman show about avenging her mother’s death comes to the ‘mecca’ of Little Saigon

- Share via

In 1996, Susan Lieu’s mother, Jennifer Ha (Hà Thúy Phường), died due to a plastic surgeon’s court-deemed “gross negligence.” Ha was there for an abdominoplasty (tummy tuck), nostril narrowing and chin implant.

For decades, her family preferred not to revisit their trauma, but Lieu, the youngest of four, always suspected they weren’t fairly compensated and wanted justice.

Before Lieu conducted a thorough investigation of her mother’s life and premature death — which she turned into a 75-minute, autobiographical one-woman show, “140 LBS: How Beauty Killed My Mother” — she says she felt like she was forgetting her. She was only 11 when her mother died.

Ha was the family breadwinner, owning two nail salons in Northern California. As Vietnamese refugees, they had achieved the American Dream, says Lieu, but then her family “fell apart,” both personally and professionally.

In “140 LBS,” directed by Sara Porkalob, Lieu plays 12 characters, including her father, siblings, husband and late mother — who she imagines telling her, very seriously, “Don’t cover up the story,” and, less seriously, “Cut the avenge mom stuff. Not cute. I don’t like.”

Lieu is currently touring the country with the show while six-months pregnant, and on Dec. 21 and 22, she’s performing it at Westminster’s Nguoi Viet Community Center.

Julie Vo — a board member of the Vietnamese American Arts & Letters Association (VAALA), which is co-presenting Lieu’s Orange County performances with VietUnity SoCal — says she knew she had to bring the show to Little Saigon.

“When I saw a clip from the show, it gave me chills,” Vo says. “These are stories that everyone talks about, but are rarely made public.”

Vo says that Vietnamese American artists and entertainers often come to Los Angeles but skip Orange County, despite it being home the biggest Vietnamese American diaspora. She didn’t want another missed opportunity.

“This is going to be crazy because this is like the mecca,” says Lieu. “And the show was made for them.”

As Lieu details in her show, she tracked down the law firm her family hired in the ‘90s and sorted through hundreds of pages of deposition. But because the plastic surgeon is now deceased and her attempts to connect with his children were unsuccessful, many of her questions led to more questions.

Why was the doctor, who was on probation with more than 24 lawsuits against him, still allowed to practice?

Why did he target the refugee community by advertising in a popular Vietnamese weekly?

“He put out this ad: if you’re Vietnamese, and you’ve been damaged by the Vietnam War, I’ll do free surgeries for you,” explains Lieu. “Thirty percent of his clientele were Vietnamese … everyone thought he was a good guy.”

Was this really all destiny, as her father insists, or was it preventable?

“It took the doctor 14 minutes after she lost oxygen to the brain to call 9-11,” she says. “After four minutes, there’s permanent brain damage. The hospital was only two blocks away.”

At the heart of Lieu’s larger-than-life story are many relatable threads.

Lieu remembers watching the popular Vietnamese American variety show “Paris By Night” every week with her family: “I say in the show, it was when we were watching ‘Paris By Night’ when we felt like we were enough even if we didn’t have that much.”

But she also remembers the adults commenting about how the female performers looked in their áo dàis (Vietnamese dresses), gossiping about how if any of them gained weight, they’d be cut from the show.

And after many episodes was an advertisement with Victoria Hạnh Phuớc, a past beauty pageant winner and owner of a popular plastic surgery clinic in Houston.

Lieu insists that she doesn’t judge people who get plastic surgery, but wants everyone to do their research.

She also wants to educate people about the Fairness For Injured Patients Act, which will appear on the November ballot in 2020 if supporters gather enough signatures from registered voters.

Since 1975, there has been a $250,000 cap on how much victims of medical malpractice can receive in California — “even if you have $18 million in damages,” emphasizes Lieu.

“If people vote for it, it’ll at least get adjusted for inflation,” she says, “which is still not good enough, but it’s something.”

Lieu now considers herself an artist and activist, but she’s a former management consultant who didn’t start taking performing seriously as a career until two years ago when she was thinking about having children. She felt like she couldn’t tell her child to go for their dreams if she didn’t herself.

“I feel more alive than I’ve ever felt. I’ve worked harder than I’ve ever worked, but at least I know that the work I’m doing is net positive,” she says.

She says that after the show, audience members greet her with both pride and tears, and it feels like a combination of a wedding and a funeral.

“For so long, I wanted to avenge my mom’s death and seek revenge on this guy,” she says. “But in the end, I was able to find out who she was.”

IF YOU GO

What: “140 LBS: How Beauty Killed My Mother.” A Q&A with competitive bodybuilder Anne Phung, 2014 Miss Vietnam of Southern California and subject of the documentary, “Fit to be Queen,” will follow on Saturday

When: Dec. 21 at 7 p.m. and Dec 22 at 2 p.m.

Where: Nguoi Viet Community Center, 14771 Moran St, Westminster

Cost: Starting at $15

Information: susanlieu.me/shows

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.