Corbin Center helps people survive the shadow pandemic of domestic violence in Santa Ana

- Share via

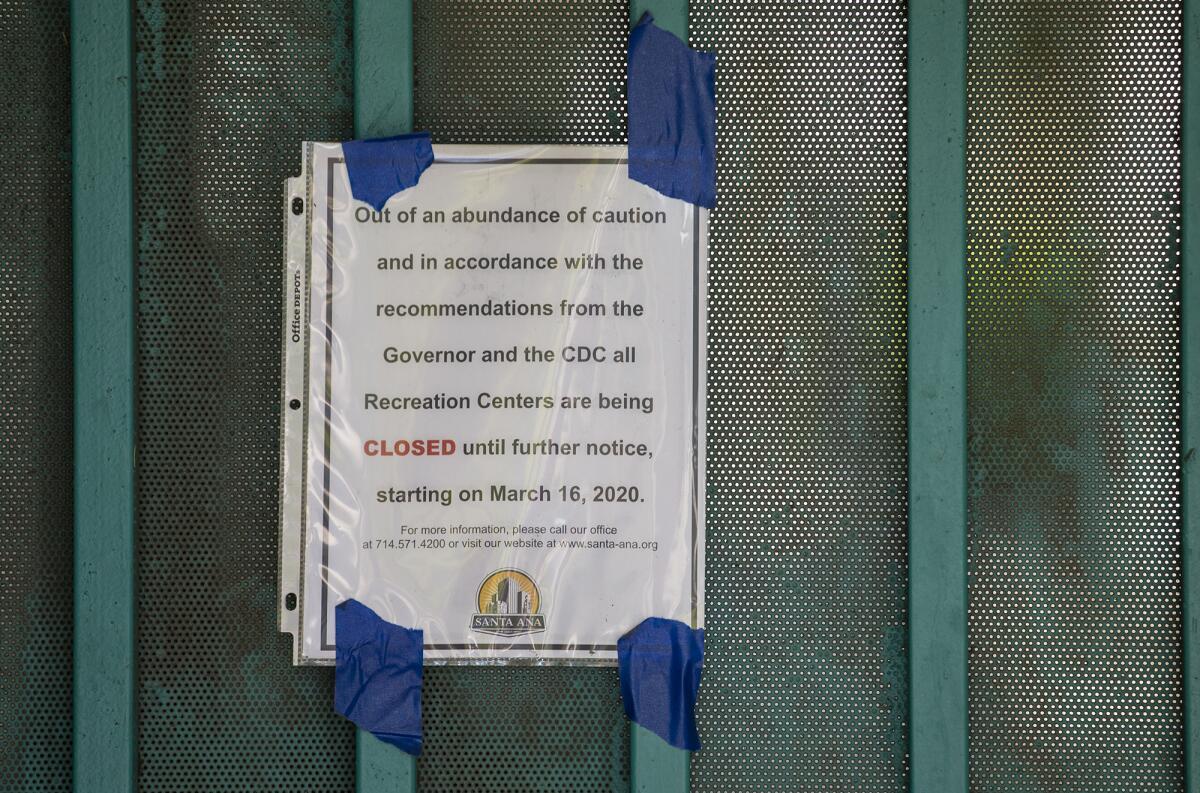

A bilingual advisory from the city of Santa Ana is taped to the locked gates of the Corbin Center, a green-trimmed building nestled beside Jerome Park. The notice stating that all such facilities remain closed due to the coronavirus pandemic may seem alarming at first, but residents in need now more than ever have not been abandoned.

Corbin continues to operate remotely, ready to help those trapped in the shadow pandemic of domestic violence, a social issue already prevalent in Santa Ana prior to the unprecedented challenges brought forth this year.

Rosa, one such survivor, is a recent success story. The mother of three suffered injuries at the hands of her ex-husband during a domestic violence incident. Through services offered at Corbin, she became employed, gained a protective court order against her abuser, sought counseling and finally reunited with her children, who stayed with a trusted relative in the interim.

At the onset of stay-at-home orders in March, victim advocates feared a rise in domestic violence cases like Rosa’s. “We anticipated it was going to get really busy,” says Ruby Godinez, a coordinator at Corbin. “All of the stressors that could lead up to domestic violence were all happening at once.”

The pandemic forced many out of work as schools turned to remote learning. Teachers, as first responders, could no longer identify bruises and other markers of physical abuse on students attending class over video conferencing apps. Fears mounted that victims would be trapped at home with their abusers while a dangerous virus spread in the community.

But for the first several weeks, all seemed eerily quiet at Corbin, a family resource center overseen by the Children’s Bureau, a nonprofit leader in the prevention and treatment of child abuse and neglect.

“There was a lot of silence,” says Godinez. “Most of the needs that came from the community changed and didn’t even focus on domestic violence.”

Prior to the pandemic, residents either walked into or called Corbin for help in domestic violence cases. Godinez, a longtime staffer, reviewed such requests and assessed their urgency before providing timely assistance, often in tandem with partnering organizations.

Human Options, an Irvine-based nonprofit that works with Corbin, saw an initial flood of concern on how to respond to abusive situations amid the pandemic.

“We saw calls to our hotline double,” says Maricela Rios-Faust, CEO of Human Options. “In the first couple weeks, we heard questions about restraining orders the most. We heard questions about what to do if the abusive partner no longer wanted to bring the kids over for visitation and was using COVID as a reason.”

And then, like at Corbin, the calls quieted down.

Long before Santa Ana became a hotspot for coronavirus cases in Orange County, its share of domestic violence-related reports per capita routinely outpaced other large cities in the state. According to data from the California Office of the Attorney General, such reports tallied 3,594 last year, averaging nearly 10 per day and marking Santa Ana’s highest peak since 2012.

More recent data from the Santa Ana Police Department shows that domestic violence-related reports during the pandemic have been fewer every month through September, a 13% decrease from the same period last year.

United to End Homelessness will host community discussions with industry experts to educate the public as part of Hunger and Homelessness Awareness Week from Nov. 15 to 22.

On the social services side, the expected tide of people seeking help for domestic violence through Corbin and other organizations appeared to arrive by summer, when coronavirus cases began to surge in California as the state relaxed its stay-at-home orders and more businesses reopened.

In any given week, Godinez says she receives about 20 referrals, enough to overwhelm Corbin’s capacity. “We used to keep all of our referrals,” she adds. “Now half of my referrals go out to other family resource centers because we don’t have enough staff to service everyone in a timely manner.”

As the pandemic heads into what health experts fear will be a difficult winter, Godinez braces herself. Whatever the next challenge looks like, she and fellow staff remain vigilant. It’s what the surrounding working class community has come to expect.

Named for Norman Corbin, a late African American reverend and civil rights activist in both the Black and Latino communities in Santa Ana, the family resource center remains a pillar since first opening in 1972.

“At Corbin, it’s the trust that residents have with the staff that creates this opening to share stories and needs,” says Rios-Faust. “Once that connection occurs, it’s an opportunity to link them to needed resources.”

As a child, Godinez’s family lived across the street from Corbin. During her childhood in the 1980s when Jerome Park was too dangerous for children like her to play at, she attended Corbin’s after-school activities.

Now, life’s come full circle.

“The community trusts us,” says Godinez. “It doesn’t feel like work. It feels like you really do make a difference every day.”

The writer is a contributor to TimesOC.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.