A Word, Please: Explaining paraprosdokians and other turns of phrase

- Share via

A sign in front of a restaurant reads: “Today’s special. So’s tomorrow.” Not the best way to tempt hungry passersby, but an excellent way to catch the attention of language buffs like Grammar Girl Mignon Fogarty, who asked on Twitter: “Is there a linguistic term for a play on words like this?”

As you can probably predict, if you keep reading, you’ll get a lesson on some language terms. But don’t miss the other lesson here: Never be afraid to reveal what you don’t know about language and grammar. Yes, it’s an intimidating subject — one that can make even the best-educated people feel deep shame over things they’re “supposed to know.” But we’re all in the same boat. So it’s no surprise that the people who know the most about language, like Fogarty, are the same people who aren’t afraid to reveal their knowledge gaps. That’s how they fill them.

I didn’t know a language term to describe that (presumably hypothetical) restaurant sign, either. In comedy, a play on meanings like this is called a “reverse.” You lead an audience or reader down one line of thinking, then you end with a twist that undermines your setup. For instance, you might want to offer your wife as an example of a point you just made, “Take my wife …” Then you pull the rug out from under the audience by adding “please!”

Turns out, there are language terms that describe this kind of wordplay, too.

The best known is probably the garden-path sentence. The concept is very similar to the comedy reverse. “A garden-path sentence is a grammatically correct sentence that starts in such a way that a reader’s most likely interpretation will be incorrect,” says Wikipedia. “‘Garden path’ refers to the saying ‘to be led down (or up) the garden path,’ meaning to be deceived, tricked or seduced.”

Grammar columnist June Casagrande explains how t’was is more than a cheery holiday contraction.

Garden-path sentences aren’t always funny. When they happen by accident, they can confuse readers: “The man who whistles tunes pianos.” Here you might start off thinking that “tunes” is a noun because it’s so standard to say someone whistled a tune. But when you read on you see that “tunes” is a verb: He tunes pianos.

Other language terms describe similarly confusing sentences. For example, “She broke her computer and his heart” has just one instance of the verb “broke” but “broke” has two different meanings applied to two different parts of the sentence. She physically broke her computer but his heart was broken only in a figurative sense of the verb. That’s called a zeugma or a syllepsis. Like garden-path sentences, zeugmas and syllepses lead readers down the wrong path. But they do so in a specific way: by using two different meanings of the same word to apply to different parts of the sentence.

Closely related to the zeugma and syllepsis is the paraprosdokian. Think of this as an umbrella term that encompasses several types of fake-out sentences including garden-path sentences and zeugmas.

“A paraprosdokian is a figure of speech in which the latter part of a sentence, phrase or larger discourse is surprising or unexpected in a way that causes the reader or listener to reframe or reinterpret the first part,” Wikipedia says.

It’s like when Homer Simpson said, “If I could just say a few words … I’d be a better public speaker.” Again, the first part of the statement is misleading. Listeners assume Homer is asking to be allowed to talk. The twist comes when you learn he meant “could” in the most literal sense: to be able.

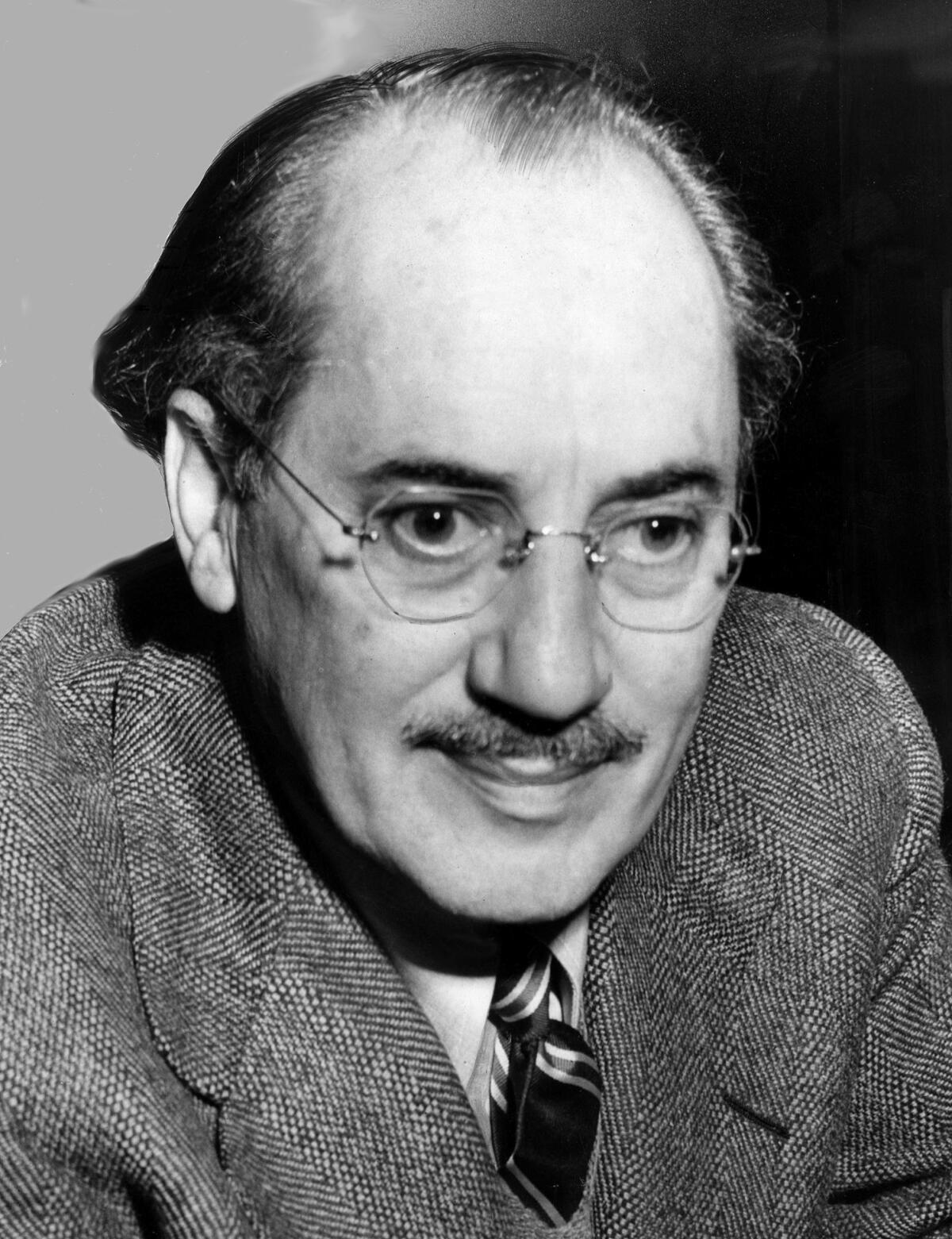

Paraprosdokian stands apart from a garden-path sentence mainly in that it doesn’t have to be a single sentence. But, as Wikipedia’s examples show, it can be: “I’ve had a perfectly wonderful evening,” Groucho Marx once told an audience, “but this wasn’t it.”

June Casagrande is the author of “The Joy of Syntax: A Simple Guide to All the Grammar You Know You Should Know.” She can be reached at JuneTCN@aol.com.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.