Apodaca: Remembering those who didn’t make it home

- Share via

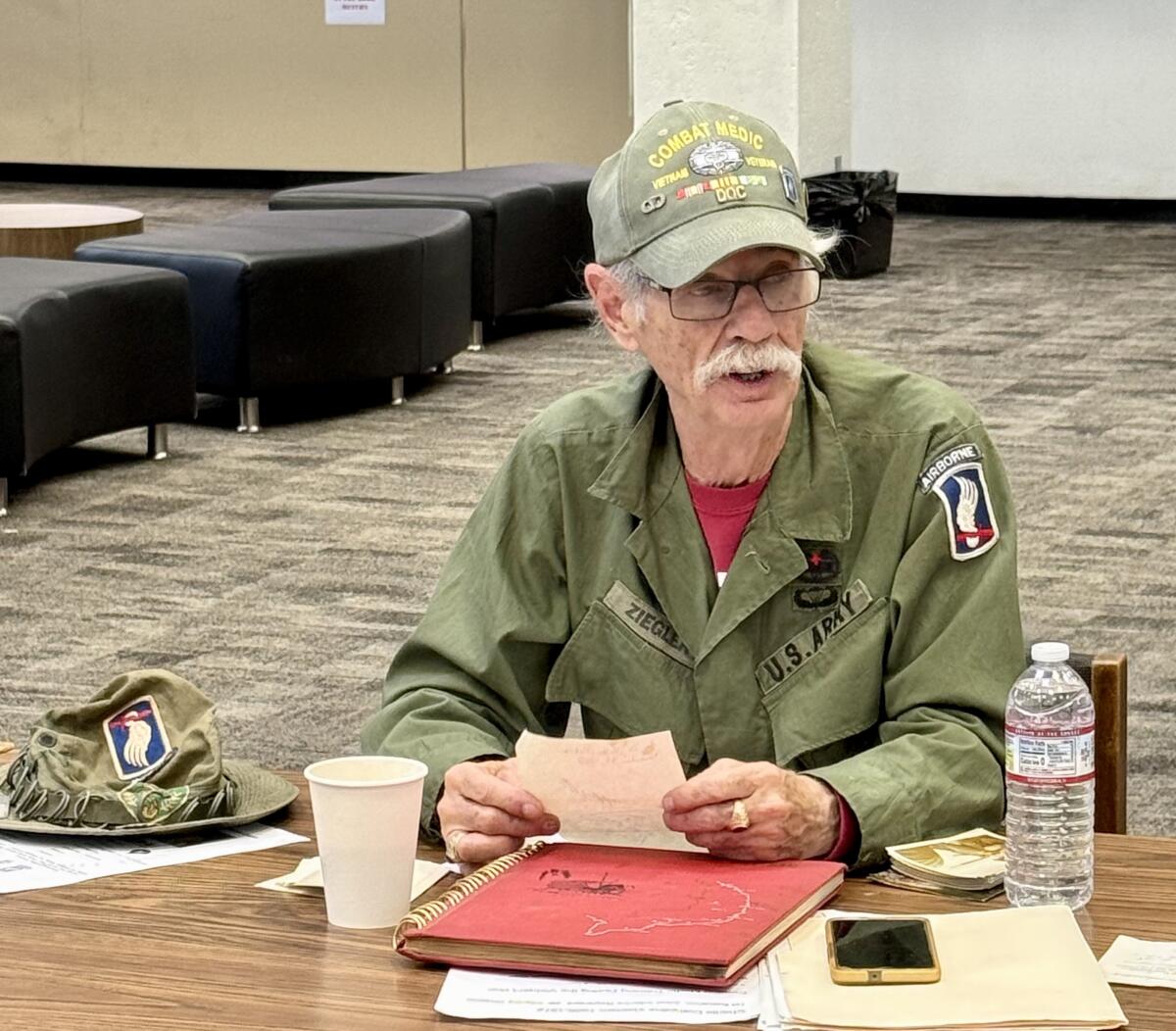

Vietnam, 1969. Wallace “Wally” Ziegler was on his first patrol as an Army medic when his platoon was ambushed. Two soldiers were grievously wounded.

Ziegler didn’t hesitate. As he worked to stabilize a soldier with a sucking chest wound from a bullet to the lungs, and a jaw that was broken in half, he recalled his extensive medical training. The cricothyrotomy procedure he had practiced on goats restored the soldier’s breathing, and he stanched the profuse bleeding from the jaw with bandages.

The injured soldier was picked up by a helicopter and Ziegler never saw him again or learned his fate. The young man was the first of many with gruesome injuries that Ziegler treated during the year he spent “in country.” Many lives were spared due to his cool expertise. A few he could not save.

Yet, even as he lugged 80 pounds of medical gear through the jungle on daily patrols, or was awakened by emergency calls from night patrols, he never complained. And in spite of knowing that his platoon could come under fire at any moment and booby traps set by the Viet Cong were everywhere, he never wavered.

One more thing he never did: carry a weapon.

Ziegler was a conscientious objector. He knew he didn’t have it in him to harm another human being, no matter the reason. But he wanted to do his part. While many COs, as they were known, served in far less dangerous assignments, he had no second thoughts about his deployment to a combat zone with a high casualty rate.

His fellow soldiers were supportive of his choice. They were all in it together, he said.

“We were all dedicated soldiers. They took great care of me because I took great care of them.”

This Memorial Day, as we fire up our grills and enjoy a day of peace and comfort, we should also recognize the holiday’s true purpose, to honor and mourn the U.S. military personnel who died in service. Ziegler is one of those who survived to tell us their stories — the ones who can truly understand and appreciate the sacrifices made.

“I think back on the ones we lost,” he said, “the ones we should honor and remember their loss, which also affected thousands of family members of the fallen.”

The chaotic guerrilla warfare in Vietnam was a brutal coming of age for Ziegler after what he describes an almost idyllic childhood in Altadena, with a close-knit family and ice cream trucks rolling down the streets. He loved math and science, and would often help out at his father’s veterinary office along with his younger brother. When he was grounded his punishment included cleaning cages.

But this picture of suburban contentment changed when he was a sophomore in high school and his mother died. The loss compelled him to assume the role of “the stoic heart of the family.”

A few years later, Ziegler headed to college at Washington State University. But his life took another turn in his second semester when he received his draft notice. During an interview that was part of the CO application process, Ziegler made it clear that he wasn’t asking to be kept out of the war.

“I said, ‘I will go. I want to go.’”

He applied for the U.S. Army Special Forces medical training, which was far more comprehensive than the medical education available in other branches. For the next year-and-a-half he crisscrossed the country to complete all the necessary courses, then he received his orders. He was deployed to Vietnam and assigned to the 173rd Airborne Unit.

Ziegler has a multitude of stories from his service there. The time in a rice paddy when a Viet Cong jumped up and started firing down the line of his patrol. The Playboy magazines that someone handed him to use as a makeshift splint for a broken leg. Blown-off limbs. The aftermath of an exploded grenade. A bullet whizzing by his head as he chatted with a guard on night duty.

Although he became adept at keeping panic at bay, one unfortunate remnant of his wartime service remains. To this day, he can’t sleep more than five or six hours a night.

After he left the army, Ziegler traveled for awhile, got married — although the marriage didn’t last — and attended medical school in Guadalajara, Mexico, where he stayed for several years.

But Southern California beckoned, and eventually he returned and settled in Laguna Beach. He left medicine behind and rekindled his lifelong love of theater.

Today, at 77, Ziegler’s peaceful life is far removed from his wartime service. As the Artistic and Audience Services Manager at the Laguna Playhouse, where he has held various positions for the past 35 years, his work allows him to split his time between Laguna and his other home in Lake Arrowhead.

Playhouse visitors will find him tending bar and greeting guests with a smile; his open, friendly demeanor a fixture at the popular theater.

But make no mistake, the tenacious medic who once fought to save lives under the most horrific conditions is still there, still remembering those who didn’t make it home.

May we all join him in remembrance.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.