‘Specter in the Gate’ illuminates a hair-raising part of O.C. history

- Share via

In 1906, flames engulfed the south side of Third between Main and Bush streets in downtown Santa Ana. The area, at one time a thriving Chinatown made up of more than 200 Chinese immigrant workers, had been reduced to a population of fewer than 20 following a racially motivated effort by the city to marginalize the community.

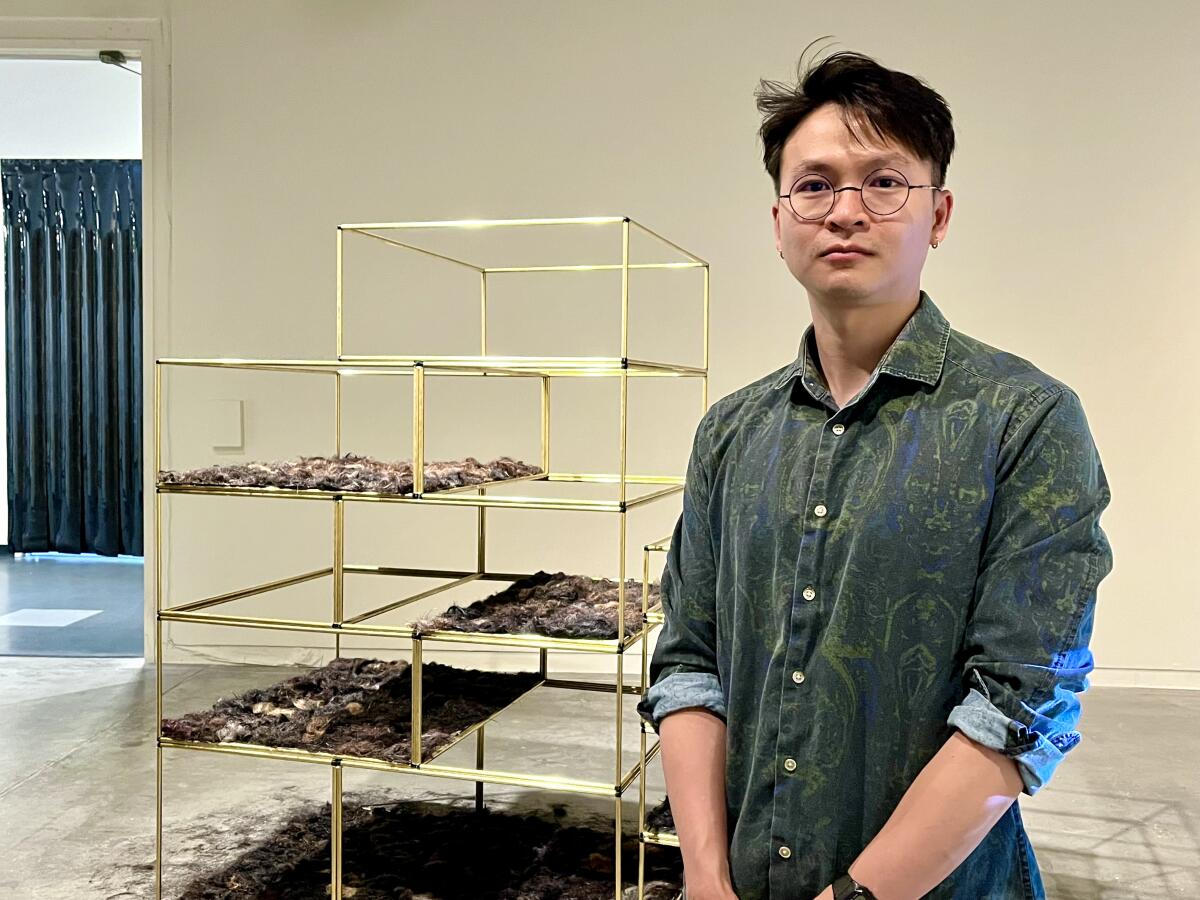

The burning down of Santa Ana’s Chinatown is the subject of Hings Lim’s “Specter in the Gate” at the Grand Central Art Center on display until May 12. The show explores the events that led to the fire and how historical narratives are remembered (or forgotten) using sculpture, photographs, moving images and a real-time projection mapping installation.

“The title of the show references the term used in film production, ‘hair in the gate,’” said Lim.

In the time before digital cameras, slivers of film called “hairs” would sometimes come loose from the film’s edge and obstruct the view of the opening at the front of a camera where the film is held in place: the gate. Lim’s installation uses human hair collected by the artist from over 25 Latino-owned salons that now operate in Santa Ana. Brass towers meant to evoke gateways found in traditional Chinese architecture are outfitted with tufts of soft, mostly dark hair that also spill onto the floor surrounding them. The past connects with the present in a way that is messy, intimate and unsettling when examined more closely.

“The hair of random people kind of references their bodies, even though they are not in this space. This line of thinking shows this past, but their bodies are not here anymore. They are missing parts of the narrative, but the hair also connects the people who live here now,” Lim said.

In 1903 the city purchased the land adjacent to Chinatown for a new city hall, and a campaign to undermine the area known as Chinatown as a dirty, rat-infested place increased. The Santa Ana Herald urged the Santa Ana City Board of Trustees to eradicate “this eyesore of the city.” By 1904 the area was subjected to constant raids.

Using projection mapping, a subtle shadow of the doorway of City Hall moves up a blank gallery wall. The projection is faint, nearly invisible; a slow ascent that gets bolder as it climbs higher.

If you were unaware Orange County once had a flourishing Chinatown or that it burned down, you aren’t alone. There is very little visual documentation of the area and its people. Lim hoped to include photos of the people who lived in Chinatown but found that hardly any such images exist. Instead, the show features framed images of City Hall that layer A.I.-generated images of Chinese immigrants from the time period, bringing them to the forefront of a history that didn’t document them.

“I spent a lot of time trying to fine-tune the images based on how people dressed during the time,” said Lim. “I am using A.I to fill in the missing spots in the archives.”

In 1906, an elderly man named Wong Wuh Ye living in Chinatown was alleged to have leprosy sores. The area where he lived was placed under immediate quarantine, and the city’s board of health hastily passed Resolution No. 416, which ordered the burning of the area. Chinatown was set a blaze that very night, while its evacuated residents looked on from a quarantine pen, and Ye was left untreated.

They were not the only ones watching. More than 1,000 people gathered to witness the fire, treating the adversity as entertainment. Lim demonstrates this with a video installation projected onto a white screen, a digital reconstruction titled “At Night (Santa Ana’s Chinatown).” Lim created the 3D rendering the way a detective might reconstruct a crime scene, using historical maps from the era and a single photograph purported to be of the Chinatown fire. As the flames burn in an endless loop, headlines from the era calling the burning flames “a big picnic” or “a Fourth of July” flash across the screen. Two lone theater chairs sit in front of the screen as the tragedy plays out over and over again. On a recent Sunday afternoon, not a single gallery guest reclined in the upholstered seats.

Lim, a Los Angeles resident, was born in Malaysia and earned a master of fine arts degree and a performance studies graduate certificate at USC. He originally worked on this project at the Santa Ana Artist Collective space with the late Maurizzio Hector Pineda. After the latter’s unexpected death, Lim was invited to become an artist-in-residence at Grand Central Art Center, supported in part by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

“Hings approached us and said he was working on this project about the burning of Chinatown in Santa Ana and asked if it was possible to show it here,” said John Spiak, director and chief curator at Grand Central Art Center. “He has been in residence with us for a little over a year, and I think the project expanded because of the size of our gallery space and having the time to think it out.”

The opportunity to finish the project left Lim with strong feelings about how the past is documented.

“Although this event was more than 100 years ago, recalling the past and conjuring it in this way was very emotional for me,” said Lim.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.