Losing ‘Sunny,’ Part 2: Who killed Adrienne Sudweeks? The hunt for clues goes cold

- Share via

Richard Johnson rebuffs questions about his girlfriend’s death, especially from people he feels haven’t earned answers.

At 6-foot-2, Johnson is a towering man with an expressive face whose voice can quickly shift from a whisper to a boom, depending on the topic of conversation. Now 50, he chain-smokes American Spirit cigarettes, though he’s vowed to quit.

Working in the taxi business since the 1990s has given him a kind of street smarts and exterior toughness that make him a great conversationalist, but also slightly unnerving.

In the years after the 1997 rape and slaying of his girlfriend, Adrienne “Sunny” Sudweeks, people would wander into Johnson’s Newport Beach art gallery and performance venue — AAA Electra 99 — and pretend to know Adrienne or inquire about years-old folklore that suggested Johnson was involved in her death.

“Murder groupies,” he’d call them before booting them out of the gallery.

If they called her Sunny, they probably didn’t really know her, Johnson says. Sunny was a childhood name that Adrienne had long abandoned. Her mom called her Sunny, but her friends didn’t use that name.

Johnson blames newspapers and police for casting a shadow of suspicion on him that has lasted more than 20 years.

He admits he may have antagonized detectives working the case by questioning their tactics and refusing to go away. His only regret, he says, is that he didn’t complain more.

The sun was up on Feb. 23, 1997, by the time detectives led Johnson out of the Costa Mesa apartment where Adrienne died the night before. They placed him in a peach-colored Ford sedan parked on Mission Drive.

Yellow police tape was strung around the trees, blocking the entrance to the unit. Inside, detectives combed the space looking for clues, jotting notes, taking photos.

Johnson climbed into the front seat of the sedan for the silent drive to the Costa Mesa police station.

A detective led Johnson through a maze of cubicles, past glass-enclosed offices and into a fluorescent-lighted interview room. A neighbor who was being interviewed in another room shot Johnson a look of revulsion as he passed.

The look provided him the first clue that some people falsely suspected he might be involved in Adrienne’s death.

A detective swabbed his mouth and genitals for DNA.

Johnson lit a cigarette, taking a couple of drags before stamping it out. Police asked him where he had been that night. He had the addresses of all his taxi runs written on his hand — numbers and street names all the way down his wrist.

After talking with police for hours, they told him he could go back to the apartment that he and Adrienne had shared and pick up some clothes.

The detectives offered a warning: Don’t go to Adrienne’s mother’s home.

Johnson didn’t realize at that point that the search for Adrienne’s killer would span 20 years.

For years after, he would rustle up young artists, musicians and friends for candlelight vigils in Adrienne’s memory outside the police station on Fair Drive. He would pester the chief and detectives for updates on the investigation.

Adrienne’s mother, Sandy Sudweeks, would call it a fixation, but Johnson seemed to view it more as seeking justice.

“I don’t do all this because Adrienne was my girlfriend. I do this because she was my best friend,” Johnson said. “And because this is what she would have wanted.”

So he ignored police advice not to visit Sandy the morning after Adrienne’s death and made the nearly 5-mile drive to her house in Westside Costa Mesa. He couldn’t bear the idea of some detective who didn’t know Adrienne breaking the news. Sandy should hear it from him, he thought.

By the time he arrived at her door early that afternoon, Johnson was hysterical. He walked into her tile entryway and tried to explain, but the words caught in his throat.

He stepped up the carpeted stairs into the living room and collapsed on the floor.

“She’s dead,” Johnson said. “She’s dead.”

Sandy figured he was on drugs, or maybe that a passenger had died in his taxi. She hadn’t been much of a fan of Johnson from the get-go, but her daughter loved him, so she did her best to tolerate his eccentricities.

“I saw her tongue sticking out,” he said quietly.

It dawned on Sandy that he was talking about her daughter. He couldn’t be, she thought.

She walked to her study and called 911. She asked the operator whether there had been a report of a death in Costa Mesa.

The operator placed her on hold.

“That’s it. That means yes,” Sandy thought.

The tension rose in her chest, and Sandy hung up the phone. When the operator called back, she asked if Sandy had a pastor.

A wave of heat moved from the top of her head, down the length of her body.

“That’s all I need to know,” she said before hanging up again.

Sandy didn’t have time to sit at home and grieve. She had been thrust into a nightmare that no parent is prepared to handle. But she had to make decisions. Should Adrienne be buried? Should she be cremated? Who should receive her ashes?

The most pressing question of all: Who killed her?

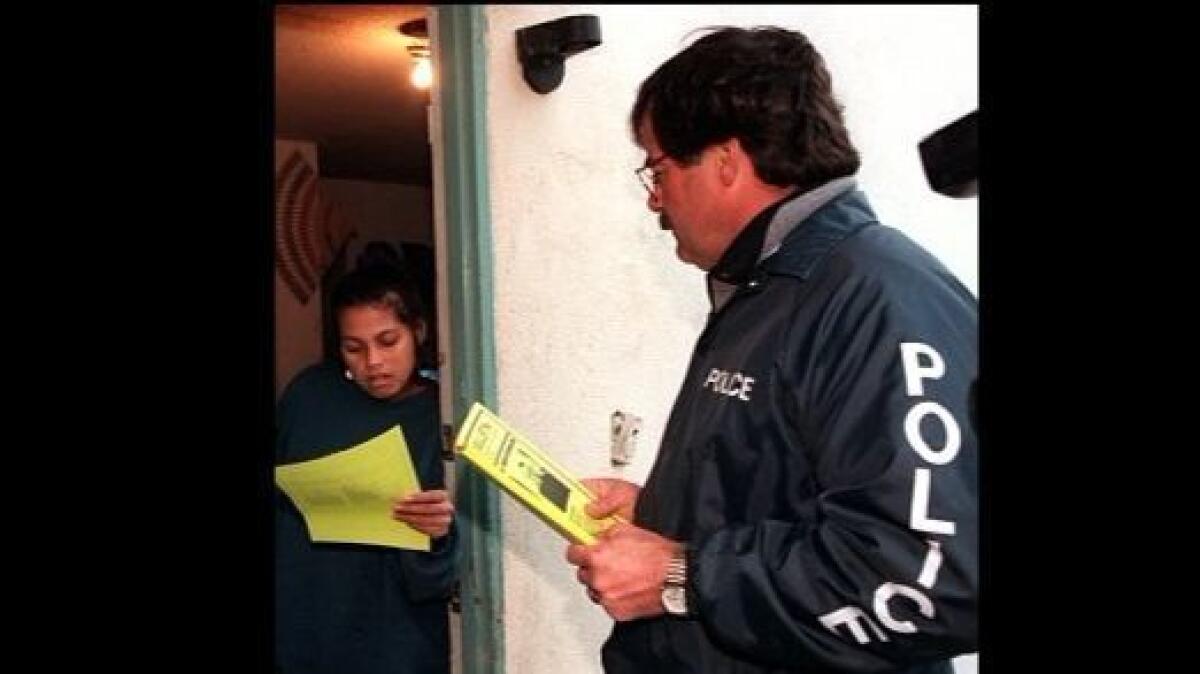

For weeks, Sandy, Johnson, some of Sandy’s students, Adrienne’s friends, family members and police detectives knocked on door after door looking for answers.

Had anyone seen anything? The answer was always no.

They taped posters and fliers on trees, poles and garage doors, offering a $5,000 reward for information about Adrienne’s death. No one came forward.

Sandy shunned journalists’ requests for information and interviews. She didn’t want her daughter to become fodder for prurient or sensationalist interests.

“This kind of thing you assume only happens in movies and to people you don’t know,” Sandy said later. “It doesn’t happen to nice, polite middle-class families. Well, that’s not true.

“I couldn’t stop her from being killed, but I could protect her in this way.”

She realized shortly that she had made a mistake. In a crime without suspects, public exposure can help solve it, she said.

Police interviewed 200 people during the investigation, and more than 130 men provided DNA samples through saliva swabs. None matched that left by the killer.

Sandy began doing interviews, posing for photographs, trying to think up angles that might interest reporters. Anything to keep the public’s eye on a case that was quickly growing cold.

This is the second of four parts. In Part 3, Adrienne’s family and friends try to carry on without her, and investigators get a break in the case.

Twitter: @HannahFryTCN

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.