High school students organized many of the recent O.C. protests, and they’re drafting action plans

- Share via

Young faces have popped out of COVID-19 lockdown to drag old institutions to an equitable age. In Orange County, teens have not only attended, but organized protests for the first time in their lives during the past three weeks.

Some will be of voting age by November, and some won’t. Those unable to vote aren’t too eager to put all their eggs into the electoral-vote basket anyway. Instead, they’ve had time to connect online, share their raw hurt and anger on megaphones, and find solutions to anti-Blackness beyond police departments.

Wismick Saint-Jean II scrolled through Twitter when he woke up on his 17th birthday and could hardly move. Although he’s usually desensitized to news, he posted a Notes app screenshot expressing an overwhelming feeling that hovered during the first days of chaotic protests.

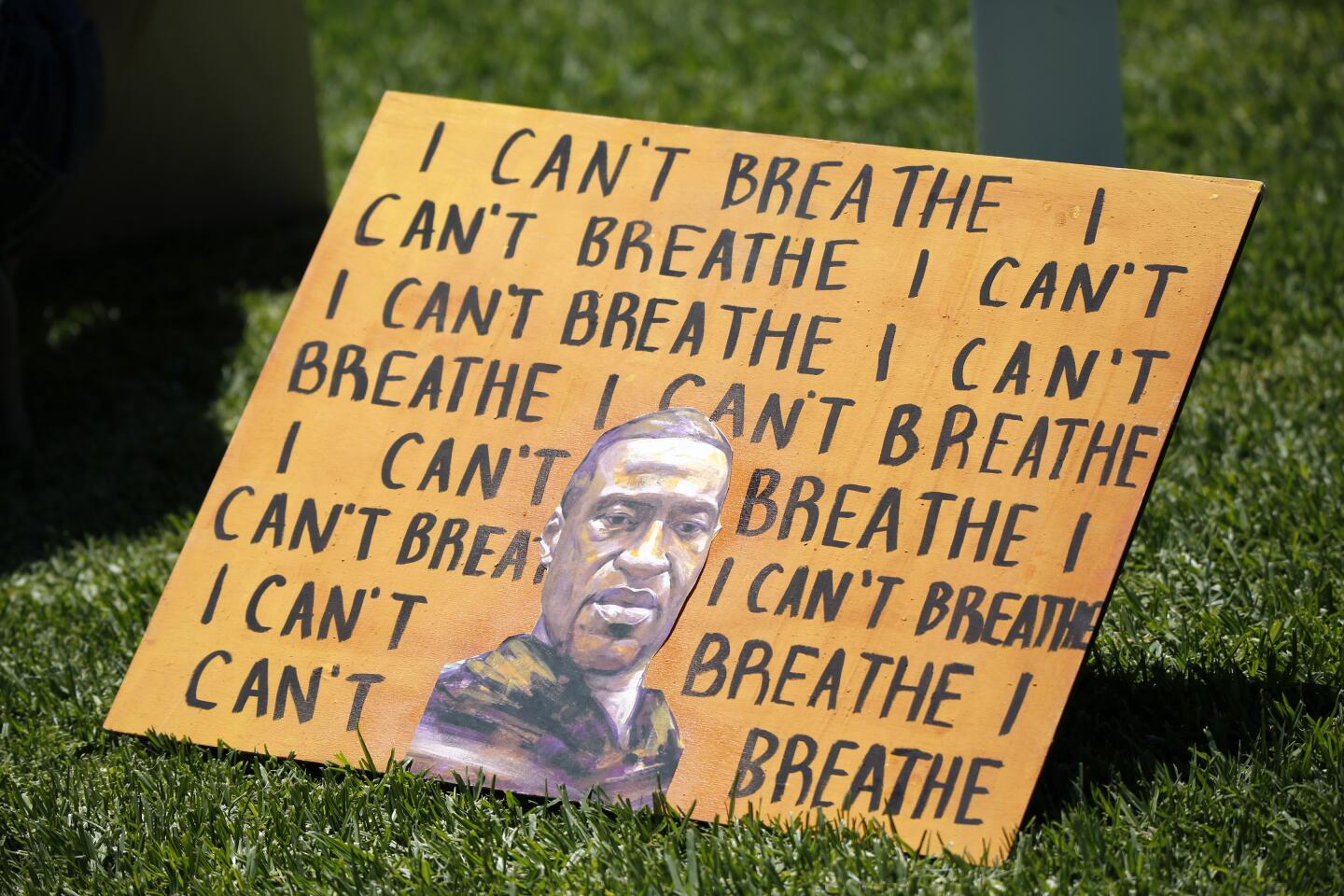

Video of George Floyd lying on the ground with a police officer’s knee on his neck had been circulating online.

The Arnold O. Beckman High School student is coming of age at a time when cycles of similar videos have been documented online. Yet, after landing in news headlines and causing short-lived uproars (if there were uproars at all), he saw that these stories often subsided into quiet obscurity.

“I’m Black in case you couldn’t tell ... I started the day off pretty rough because I couldn’t sleep,” Saint-Jean said on Instagram livestream the day after his birthday. “I went to bed that night after scrolling through Twitter for God knows how long looking at videos of protests, of police violence ... this was just too much for me to handle.”

While he appreciated people leaving “Black Lives Matter” and other messages of support in comments to his post, he was also hurt by it.

He said it’s performative activism — showcasing that you care rather than serving the community you are targeting. He uses Blackout Tuesday, the social media initiative to post black squares and go silent in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, as an example.

He started the hashtag #moneywhereyourmouthis, encouraging his Instagram followers to donate at least $10 to organizations supporting protesters, take a screenshot and tag people to participate.

Using his birthday cash, Saint-Jean started the campaign off by donating $100 to the Atlanta Solidarity Fund, which helps bail out activists who are arrested during demonstrations.

Talia, a Beckman High School student who only gave her first name, didn’t have money but still wanted to do something.

“I remember asking him, ‘Do you have any suggestions? Because I don’t have a job. I can’t donate. Is it crazy to have a protest of our own?’” recalled the 15-year-old, who is white.

It took about a week to organize. They invited speakers from various schools across O.C., created Instagram posters and bought a megaphone.

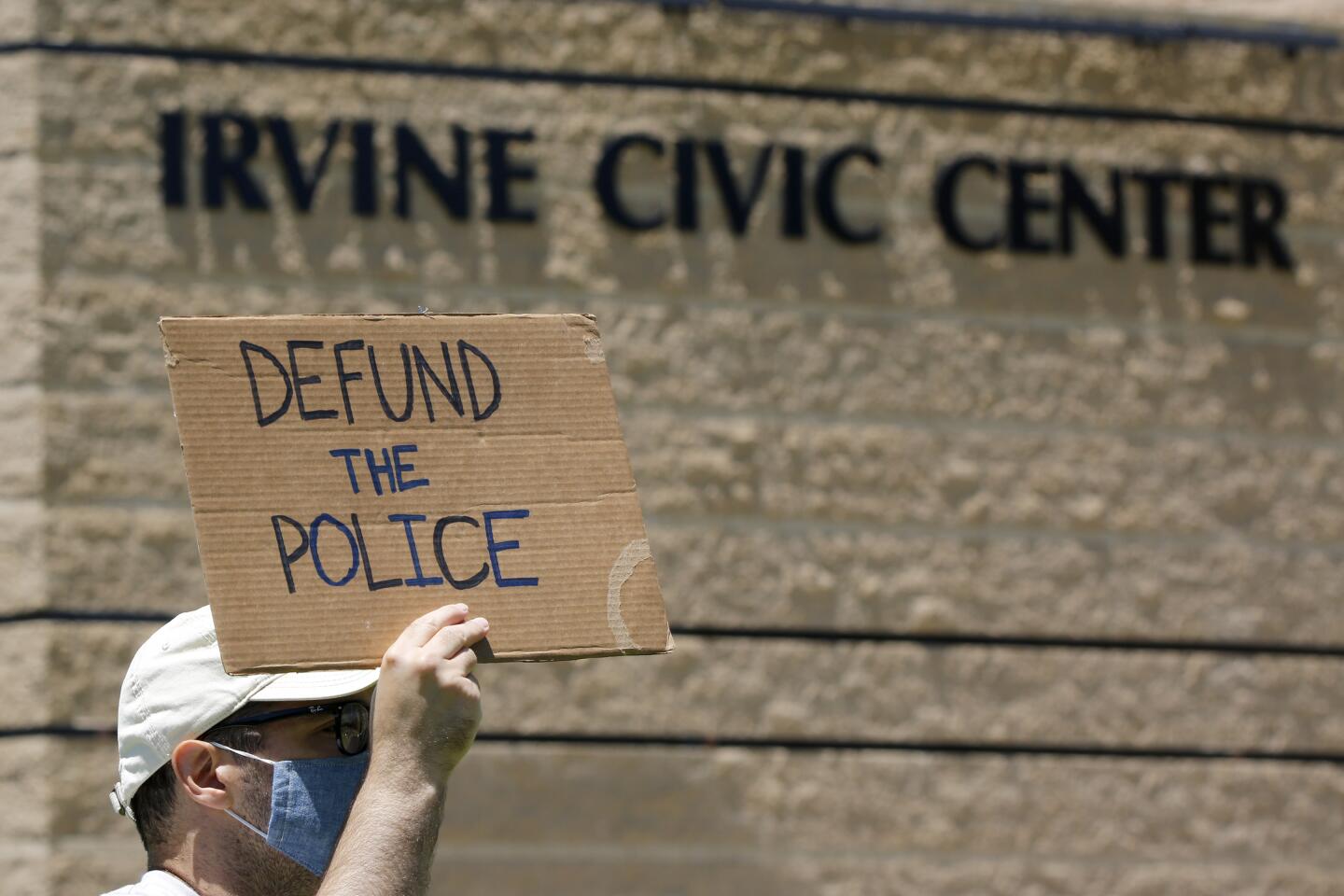

Hundreds sat on the lawn of Irvine Civic Center on June 13 to listen to the line-up of speakers as cars honked in support, including a Weedmaps delivery van whose passenger held up a “Black Lives Matter” cardboard sign as it drove by protesters.

At Huntington Beach High School, 18-year-old Kara Tran-Wright, president of the school’s Black Student Union, hosted a virtual meeting inviting students from other clubs to listen to students speak about the history of police brutality and how it connects to current events.

Teachers and community members were also welcomed to join.

“We needed a space to talk about what’s going on and how we feel about it, especially as an upcoming generation,” said Tran-Wright, who is Black and Chinese.

The next day, another student suggested they should continue to have meetings and organize a protest. A group of five students from multiple clubs collaborated, with the help of O.C. Human Relations, to hold the demonstration at Worthy Park on June 5, their last day of school.

“Our parents were wary about us going to a big protest at the pier because you see a lot of white supremacists there,” said Tran-Wright. “It’s unsafe.”

Although she helped organize it, she didn’t attend the protest because she has an immunocompromised family member and decided not to risk it.

Lauren Harvey, an 18-year-old student in Model United Nations and the young Democrats club, said “having a student-led protest was really important to us, because we really wanted to show that our high school, in particular, was behind the movement.”

The protest was organized for Huntington Beach High School students only.

Harvey, who is white, attended the demonstration and estimates that a little more than 100 students and a few teachers showed up.Growing up Black in O.C.

“In general, seeing faces that look like you is a rare occurrence growing up Black in Orange County,” Saint-Jean said.

He’s entering his senior year in a few months, and so far he’s never had a Black elementary, middle or high school teacher.

According to the California Department of Education, Beckman High School has two Black teachers, and Tustin Unified School District has 12 Black teachers.

He recalls being singled out for his race in games of tag, dealing with racist jokes, people touching his hair and being perceived as more violent during elementary school.

“The experience can be very upsetting and can make you feel like you have to be a smaller person,” Saint-Jean said. “That’s another big part of why I’m [organizing]. I could have done this a long time ago, but so much of it was uncertainty about being too loud about our issues, too aggressive.

“I and a lot of other Black people don’t care anymore. I simply do not have time or the energy to coddle the feelings of people around me while people are dying in the street.”

At Huntington Beach High School, Tran-Wright hears “a lot of hate speech, a lot of the n-word being thrown around. You see kids with Confederate flags, students who behave similarly to white supremacists. You feel very unsafe walking on the street. You’re not necessarily welcomed.”

In a CDE report for the 2018-19 school year, Huntington Beach High School did not employ any Black teachers and only employed three throughout the city’s public school district.

“I don’t think I ever truly realized how bad it was in Huntington Beach until fairly recently when all the stuff about the Newport Harbor High School students [surrounding a table with Solo cups in the shape of a swastika] became a big deal,” Harvey said.

The latest U.S. Census Bureau information reveals O.C.’s Black population remains at 2.1%.

Saint-Jean’s mom, who initially immigrated from Haiti to Florida, remembers being pulled over a few months after moving to Irvine about 10 years ago.

She was driving a Mercedes-Benz 350 and, without asking for her name and driver’s license, was accused of stealing the car. She recalled the police officer telling her that she needed to go back to where she came from — Los Angeles.

For the Saturday Irvine protest, his mom took the day off work to attend. She works two jobs as a nurse. His dad, who was politically active in Florida, and older sister, a University of California Irvine student, also came to support him.

“Nothing has changed,” Saint-Jean’s dad said. “These kids are complaining about the same things. You mean to tell me they cannot find a Black person who is qualified to teach high school?”What’s next?

The protests are stretching past Juneteenth, a holiday celebrating the end of slavery in 1865. Teens are looking for ways to make the momentum of the demonstrations last.

Tran-Wright said the Huntington Beach group is in the middle of planning another event.

Saint-Jean has set his sights on creating a multi-school movement encouraging O.C. youth to educate themselves and others on Black history.

Behind-the-scenes, he reached out to students in Black Student Unions from multiple schools, including Orange County School of the Arts, Santa Ana High School, Northwood High School and University High School.

The students are collaborating on creating an action plan to present to the O.C. Board of Education. They are demanding diversity in teacher staffing and curriculum, transferring of funding for on-campus police to mental health resources and a better anti-discrimination policy with clear disciplinary action procedures.

At the same time, the Irvine protest speakers urged people to sign a petition to vote Mayor Christina Shea out after facing criticism for comments made about Black Lives Matter protests.

Patriotic banners hang high on light poles near the Irvine Civic Center. They read “Land of the Free” and “Liberty and Justice,” and below, the names of Black lives cut short at the hands of police are scrawled on the concrete in chalk. And they’re already fading.

Out of three columns of names, Akai Gurley, Alton Sterling, Walter Scott, Eric Garner and Philando Castile are still readable, but Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and Tony McDade are no longer visible on the street.

Their names leave a legacy on the young minds of a generation so hungry for change. But it doesn’t come without risks.

The youth-led nonprofit MEEP Shows, or “More Empowering Events Please,” hosted one of the first protests in Orange County in Santa Ana and held a second in Garden Grove attracting thousands.

Since then, MEEP’s Nicole Nguyen, who recently graduated from Garden Grove High School, was verbally harassed at work for helping organize the protests.

Nguyen said the man who approached her at work knew her full name, expressed hate messages and argued “All Lives Matter.”

He left on his own, leaving her shocked and panicked. Her coworker reported it to the company’s Human Resources, and now she wears a fake name tag and works with the company’s security posted nearby.

“There’s still a lot of untouched racism in Orange County despite how diverse it is,” Nguyen said. “I feel like as a person of color, I and other teenagers should be standing in solidarity with Black lives. There are so many social issues to take into account.”

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.