Ex-JDL member sues U.S. government over parole hearing Alex Odeh’s family, ADC addressed

- Share via

A lawsuit filed in federal court seeks to deliver Robert Manning the freedom the U.S. Parole Commission denied him in late 2020.

The former Jewish Defense League member currently sits in a prison cell at the Federal Correction Institute in Phoenix, a medium-security facility, where he is serving a life sentence for the 1980 mail-bomb murder of Patricia Wilkerson, a Manhattan Beach secretary.

During the Nov. 3, 2020 parole hearing, Wilkerson’s daughter, Pamela, addressed the commission about the crime Manning was extradited from Israel to stand trial for in 1993.

As in 2018, Helena Odeh, the daughter of slain Palestinian American activist Alex Odeh, and Samer Khalaf, president of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, also testified as Manning’s victims — a critical point of contention in the complaint, which names the Justice Department and the U.S. Parole Commission as defendants.

No suspects have been publicly named by the FBI in the Oct. 11, 1985 pipe bomb attack on the ADC’s office in Santa Ana that claimed Odeh’s life; Odeh served as the civil rights group’s West Coast regional director at the time of his assassination.

As recently reported, retired Santa Ana Police Department Lt. Hugh Mooney recalled Manning being one of two names disclosed to him at the crime scene he commanded by a group of FBI agents and Los Angeles Police Department Joint Terrorism Task Force members.

The revelation prompted U.S. Sen. Richard Durbin to author a letter to FBI Director Christopher Wray asking for an update on the ongoing probe.

“This heinous case of domestic terrorism must be professionally investigated and, finally, resolved,” Durbin wrote. “In order to preserve the rule of law and deter future would-be attackers, the terrorists who murdered Alex Odeh must not escape accountability.”

The FBI originally named the JDL as the “possible responsible group,” in 1985 before backtracking. The agency would later deem the JDL a “right-wing terrorist group” in its “Terrorism 2000/2001” report.

Back in 1988, sources close to the investigation in California and New York informed The Times that Manning was one of several suspects in the Odeh case.

But the decades-old cold case remains unsolved without charges ever having been filed.

“The Parole Commission allowed politically motivated persons and advocacy groups, acting under the pretense that they were ‘victims’ of Manning, to provide false and defamatory information,” the suit alleges. “The 1985 incident bore no relationship to the 1980 crime that was the basis of Manning’s conviction and sentence.”

Filed in the Southern District of New York, the suit describes the parole hearing as a “travesty,” one that violated Manning’s due process constitutional rights and protection from cruel and unusual punishment.

Paul Batista, a well-known novelist, television personality and attorney, is representing Manning in the case. He previously sued the Justice Department on Manning’s behalf in 2016 after the government initially approved his inmate transfer request to Israel before revoking it weeks later; a judge ultimately dismissed the suit.

“I have a client whose legal and constitutional rights have been violated, and I am committed to vindicating those rights,” Batista said of his current suit. “Manning, in effect, has been condemned to death in federal prison on the basis of guesswork by nonvictims.”

Senate Judiciary Committee Chair demands cold case be “professionally investigated” and “resolved” in letter to the agency.

The U.S. Parole Commission didn’t respond to a request for comment.

According to audio of the hearing obtained by TimesOC, Odeh and Khalaf’s testimony raised questions from Allen Lowy, the pro bono attorney who represented Manning that day.

“How is that person a victim?” Lowy asked Oscar Vela, a hearing examiner with the Parole Commission, before Odeh testified.

“You can ask that after,” Vela responded sternly. “Do not interrupt. You interrupt like this, I will ask you to leave the hearing.”

Odeh gathered herself before linking Manning to the loss of her father.

“We were robbed of a childhood filled with a father’s love because of horrific actions of people who wanted my father gone,” Odeh stated. “Robert Manning was one of those men.”

Vela asked Odeh to address a “reasonable request” and explain her interest in Manning’s case and parole eligibility. She deferred to Khalaf.

“Manning was supposed to, in fact, cooperate with the FBI,” he claimed. “Our understanding is that he has not done that and he has refused, therefore we’re both appearing as interested parties.”

Vela noted for the record that he possessed a document sent by many interested parties but offered no further comment on it; Khalaf continued his testimony.

“Like the Odeh family, the Wilkersons suffered from the crimes of Manning,” Khalaf said. “He has never shown any remorse for his actions, nor has he accepted responsibility for the pain and anguish he has caused. The FBI knows that Manning played a role in the murder of Alex Odeh. However, Manning has stood fast against cooperating with the FBI to bring his accomplices to justice.”

Lowy pushed back against any such notion during the hearing. He claimed that FBI agents visited Manning before recent parole hearings and inmate transfer requests and offered his release in exchange for information about the murder.

“Manning could have been home for years,” Lowy said. “He simply doesn’t know.”

Batista excerpted both Odeh and Khalaf’s testimonies in the complaint. He singled out Khalaf’s statement as “baseless,” “vindictive” and “defamatory.”

The ADC declined to comment on the suit but noted that the organization stands behind Khalaf’s comments at the hearing.

Since the Odeh case arose during testimony, Manning took the rare occasion to address allegations of his involvement.

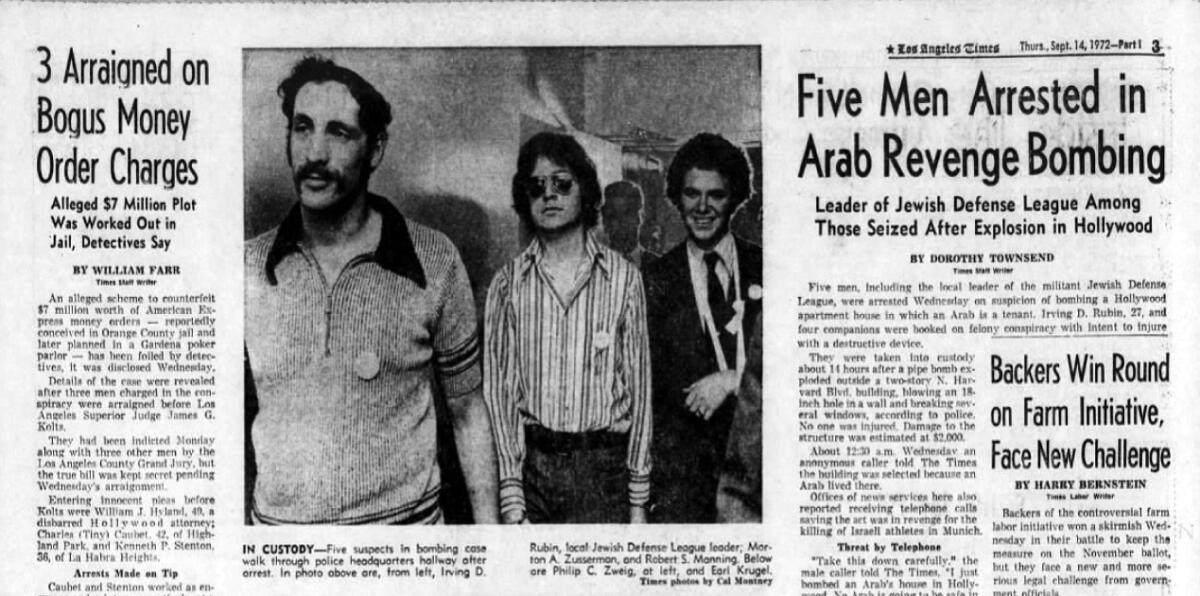

The Los Angeles native claimed to have left the JDL in 1973, the same year he promised to sever ties with the extremist group after having been convicted in the bombing of an Arab American’s Hollywood home in retaliation for the Munich massacre carried out by Palestinian terrorists during the Summer Olympics.

His misdemeanor convictions for assault likely to do great bodily harm and illegal possession of fireworks carried a sentence of three years’ probation and a $250 fine.

Manning acknowledged he had spoken with the FBI but said he knew nothing of the Santa Ana bombing. “There was a thing about an airplane ticket,” Manning said, “and I told them I was going to try to find out who had that ticket.” He claimed efforts to do so proved in vain, since he had no involvement in the plot and wasn’t even in the country on account of being on reserve duty with the Israeli army when Odeh was murdered.

It wasn’t the first time Manning laid claim to a purported alibi.

Thirty years ago, in a story republished on the now-defunct Torah Voice website, Manning recounted when an FBI agent allegedly harassed him during a trip to the United States in 1986. Manning claimed to have shown the agent his American and Israeli passports as proof he was in Israel during the Santa Ana bombing in response to the agent’s assertion that an airline ticket showed him traveling across the U.S.

At the parole hearing, he offered to stand trial for Odeh’s murder.

“If they say I’m the top subject, then charge me for it,” Manning said, “and I’ll go to court and prove my innocence.”

“You’re denying any involvement with the death of Mr. Odeh?” Vela asked.

“Absolutely, absolutely, without a shadow of a doubt,” Manning said.

The focus of the parole hearing shifted back to the question of his behavior in prison and assessing the likelihood of him committing future crimes if granted parole, “the only two criteria that should have been considered,” the suit argued.

Manning told the commission that he began the process of rehabilitation in prison on day one and had made strides. If released, he planned to live a quiet life in retirement in Los Angeles, not Israel. A case manager and a chaplain spoke on how he hasn’t been a behavioral or managerial concern and is considered a tolerant presence in the prison’s religious services department.

But Vela considered the totality of Manning’s crimes and found his responses to the Wilkerson murder less than forthcoming. The hearing officer didn’t believe Manning’s testimony that he had merely supplied bombmaking materials but never understood it to be for a contract killing.

“You’ve come to prison and you’ve done what you needed to do,” Vela said, “but I still feel based on the history of your criminal actions that there’s a reasonable probability, if you are released in the future, you will commit a federal, state or local crime.”

Vela denied Manning‘s parole without mentioning the Odeh case, citing, instead, circumstances surrounding the Wilkerson murder in his concluding comments.

According to the suit, Manning appealed the decision on March 12, 2021 only to have the denial of parole upheld later that June.

As in Batista’s previous legal effort to have Manning’s inmate transfer to Israel restored, he portrayed his client as frail and in ill health.

“He is 69 and highly infirm,” the complaint read. “He is incapable, for moral and physical reasons, of committing another crime if released.”

Batista hopes his latest legal challenge will convince a judge to reverse the commission’s decision and grant Manning immediate release from prison on parole.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.