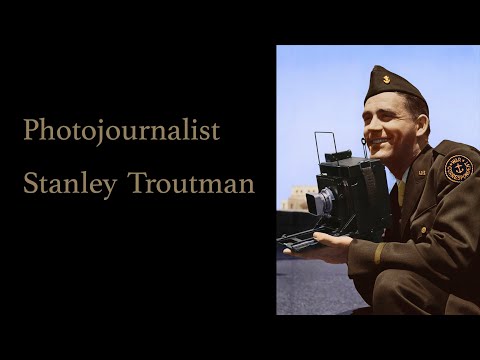

Newport’s Stanley Troutman went to war armed only with a camera

- Share via

In the waning hours of World War II, Stanley Troutman made a rebellious decision to trade one historic scene for another.

It involved ditching Gen. Douglas MacArthur, who was about to sign the Japanese surrender to end the hostilities on Sept. 2, 1945. Troutman, a civilian photographer in the American war picture pool, had a choice spot for the ceremony on the USS Missouri.

Then one of his colleagues told him there was a chance to travel to Nagasaki. They would be the first American civilians to document the aftermath of the atomic bomb that had destroyed the Japanese city nearly a month before.

As Troutman told a Corona del Mar High School student for a living-history project in 2018, MacArthur had grounded correspondents’ planes because he thought photos showing the ruins of Hiroshima, the first Japanese city hit by an atomic bomb, credited the Army Air Forces with winning the war that he had poured himself into. Some of those photos had been Troutman’s.

The newsmen hit up other planes — the brass was preoccupied— and scavenged the fuel they needed for the 600-mile flight from Tokyo Bay.

“Hiroshima made me famous, so I was going to stay with the Air Force,” Troutman told the Daily Pilot in 2002. “I wanted to be loyal.”

Troutman was dedicated to capturing moments — from Hollywood frivolity to the grit and devastation of war to the sports legacy of UCLA to the majesty of a Corona del Mar sunset.

He died of pneumonia Jan. 2 in Newport Beach. He was 102.

Only in his last 20 or so years did he speak much about his combat photography.

“For a long time, he didn’t think he was doing anything important,” his wife, Patt, told the Pilot in 2002.

Letters of commendation from generals showed they thought differently. He saved them, and his daughter Gayle Rindge proudly shows them, neatly and modestly catalogued in plastic protectors in a zippered binder.

One is even from MacArthur, who awarded him the Asiatic-Pacific Service Ribbon, although he was a civilian.

Stanley Madison Troutman was born Oct. 3, 1917, in Pasadena and grew up in Echo Park.

He joined Acme Newspictures in Los Angeles at age 22 as a darkroom assistant before becoming a general assignment photographer, snapping homicide and earthquake scenes, Golden Age film premieres, sensational trials and at least one freak snowstorm. He made $16 a week.

He was exempt from the military draft because his journalistic work was considered essential on the home front. But he felt joining the war effort was the right thing to do, Rindge said.

So in 1944, he volunteered to photograph in World War II’s Pacific Theater. He embedded with the Navy first, with no combat training and no weapons, just a rugged, 6-pound large-format Speed Graphic camera with unlimited, government-issued 12-frame packs of film specially designed for the harsh elements. He also tied in with the Army and Marines.

He shot battles, quiet moments of exhaustion and pain, palpable moments of relief and tenacity. He shot at Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands, the reclaiming of Corregidor in the Philippines, the liberation of the Chapei internment camp in China. He immediately sent off his film by courier and didn’t see any of his work until after the war.

Sometimes he got a reminder to “don’t go with the first wave, we want you alive,” Rindge said recently, surrounded by her father’s archive in the dining room of his Corona del Mar home. His detailed captions are attached to the photos in Teletype ink faded to purple.

His last war assignments were at the sites of the two atomic bombings.

One of his iconic frames was of the former Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, largely intact but damaged on the splintered moonscape of the once-vibrant city.

In the center-weighted shot, Life magazine writer Bernard Hoffman stands in the rubble facing the building, its distinctive dome skeletal but upright. The ruin is now the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, or Genbaku Dome.

Rindge, 72, saw the Genbaku Dome photo in her schoolbooks but didn’t know her father had taken the shot. She thinks he was traumatized by what he witnessed in the Pacific.

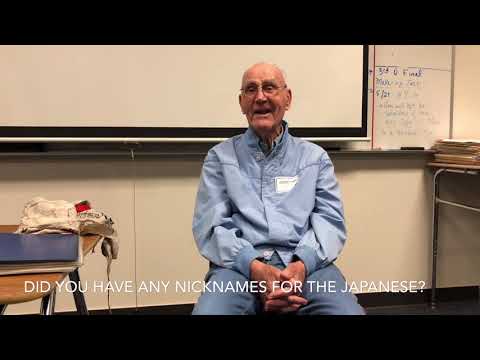

“No,” he told the CdM student when asked if he had any enjoyable moments. “It wasn’t enjoyable at all.”

After the war he returned to Acme —which was later purchased by UPI — and reached the rank of Los Angeles bureau manager. In 1946, he followed an Acme colleague, Vic Kelley, to UCLA and became the first official campus photographer. Troutman’s body of work ranged from student ID portraits to sports action to head-of-state visits.

He loved football coach Red Sanders, who was friendly to him. Troutman missed a football game to film the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne, Australia. It was one of the few games he skipped.

“It’s not easy to picture how UCLA will get along without Stan’s photographic wizardry and, even more, his instant and cheerful responses to the need for recording campus events on film, both still and motion picture. And recently videotape has been added to his bag of tricks,” a campus newsletter stated in announcing Troutman’s retirement in 1980.

Ken Norris was 13 when he met Troutman at a Los Angeles Rams game in 1976 as Norris was splicing and editing 16mm game film. Troutman took to the precocious cinematographer, who is now UCLA’s director of video operations.

Troutman was a friend, mentor and legend, Norris said.

“I firmly believe the secret to his longevity was his noontime siestas. Each day after lunch, Stan would kick off his shoes and nod off for one hour, then always returned to work refreshed and ready to go,” Norris said. “I only wish I would have realized his secret in life a lot sooner.”

Torin Boyd is a photojournalist and photo historian who came across several Troutman photos in his collecting. After seeing a recent portrait of him last year and learning that he was still alive, Boyd arranged to interview him for a documentary film.

He thinks Troutman’s best image was one of a fatigued Marine weeping with his head in his hands during the Battle of Peleliu in 1944. Troutman waited until the man’s face was obscured to make his shot.

Troutman received the Lifetime Achievement Award in 2004 from the Press Photographers Assn. of Greater Los Angeles, which gives a scholarship in his name. He never had an exhibition during his lifetime, but Boyd has arranged for one at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan in April. Rindge secured one to open in November at the Heroes Hall veterans museum at the OC Fair & Event Center in Costa Mesa.

Troutman was preceded in death by his first wife, Betty Jean, and second wife, Patt. He is survived by three children, Barbara, Gayle and Mark; eight grandchildren; 19 great-grandchildren and one great-great-grandchild.

He lived in Corona del Mar his final 24 years.

Every night, he traveled the one block from his blue mid-century cottage off Poinsettia Avenue to Inspiration Point, first unassisted, then with a walker, then a motorized chair. He also was active with the Oasis Senior Center, where he led the Pledge of Allegiance once a month.

And he made photos.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.