O.C. Ed Department forum tries to dispel myths about ethnic studies, critical race theory

- Share via

As critical race theory — the examination of institutions through a lens of racism and inequality — becomes a nationwide political flashpoint, ongoing efforts by schools to promote inclusivity, in part, by offering ethnic studies courses have come under fire.

Now, county education officials are attempting to separate fact from fiction by hosting discussions to update the public on what is and isn’t being taught in local classrooms.

In a virtual colloquium Wednesday hosted by the Orange County Department of Education, scholars and educators shed light on the origins of a recently approved statewide model curriculum for teaching ethnic studies in public schools.

The event preceded two similar panel discussions on ethnic studies and critical race theory being hosted by the Orange County Board of Education, which sets policies for OCDE, on Tuesday and Aug. 24.

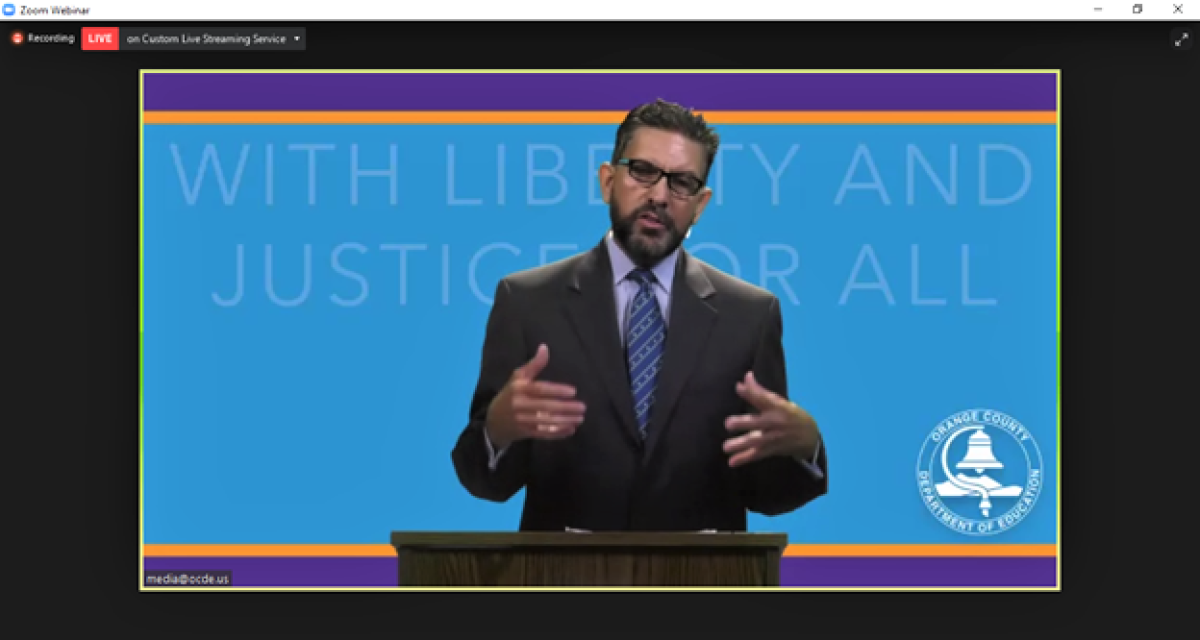

“With Liberty and Justice for All” convened experts, university researchers and superintendents from four school districts, who shared the potential values and benefits of such coursework on students of all backgrounds.

Supt. Al Mijares, who moderated the discussion, explained the county office received several requests from local school district officials for the department to provide an overview of the state model curriculum and clear up misconceptions about critical race theory being taught to students.

“To be clear, ethnic studies is not synonymous with critical race theory,” he said. “But we also cannot omit structural injustices from our history.”

While state lawmakers consider legislation that would make such courses a high school graduation requirement, many Orange County districts — including Anaheim, Santa Ana and Los Alamitos unified school districts — are already teaching or creating classes, mainly as electives.

Courses include texts from a diversity of authors, cover the contributions made by people of color in government, science and the arts and create a space for students to share their own cultural touchpoints, questions and concerns.

“We are at a critical juncture in this county in terms of trust — trust in things like law enforcement, trust in government, trust in religious institutions…and trust in our public schools,” said Michael Matsuda, superintendent of Anaheim Unified, where officials in May made ethnic studies a required course.

“Ethnic studies builds trust in schools, in affirming identity. And that trust begins with connecting to oneself and to others.”

Administrators shared how their districts are creating coursework to respond to demands from students and families to see history and institutions from more than just one perspective.

Gregory Franklin is the superintendent of Tustin Unified, where an ethnic studies elective will be offered in the fall. He refuted the claims of critics who’ve raised concerns that such teachings would separate races into oppressors and victims and potentially shame white students.

“There are a lot of people who haven’t been good actors in history,” he said. “Nobody should be feeling guilty about that in class, but if we’re not honest about where we’ve been, it’s going to be very difficult for us to go forward together.”

Early research indicates participation in such coursework has the potential to improve academic behaviors and outcomes among at-risk students.

A 2016 study co-authored by UC Irvine education policy researcher Emily K. Penner found students who elected to take ethnic studies courses increased school attendance by 21% and improved their GPAs by an average of 1.4 points compared to a control group.

Kimberly Young, who teaches ethnic studies classes at Culver City Unified School District and serves on the state’s Quality Instruction Commission, said such classes can be powerful places for students to think critically, learn and grow.

“My classroom is not a space of indoctrination. It is a place where students are free to ask and explore questions they have about histories that have been excluded from our traditional curriculum,” she said. “Ethnic studies empowers all students to engage socially and politically and think about the world around them.”

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.