Longtime councilman Kelly Boyd, a ‘Laguna Beach icon,’ looks back as he enters retirement

- Share via

A light breeze lifted off the ocean and floated over Laguna Beach, through an open door and into a living room illuminated by the glow of the Marine Room Tavern’s old neon sign. Sitting on a couch at home between his coastal view and the memento from his former bar in the kitchen, Kelly Boyd took a swig of beer and let out a raspy laugh.

“I’m still getting calls from people: ‘Kelly, can you help me with this? Kelly, can you help me with that?’” he said. “I’ll still help people out if I can.”

After a cumulative 16 years (including the past 12) on the City Council, 25 years as owner-manager of the Marine Room and a lifetime as a Laguna Beach resident, Boyd knows almost everyone in the city.

“It’s evident that nobody knew more people in town than Kelly,” said six-term Councilwoman Toni Iseman, who served alongside Boyd for his last 12 years on the dais. She called him “Mr. Laguna.”

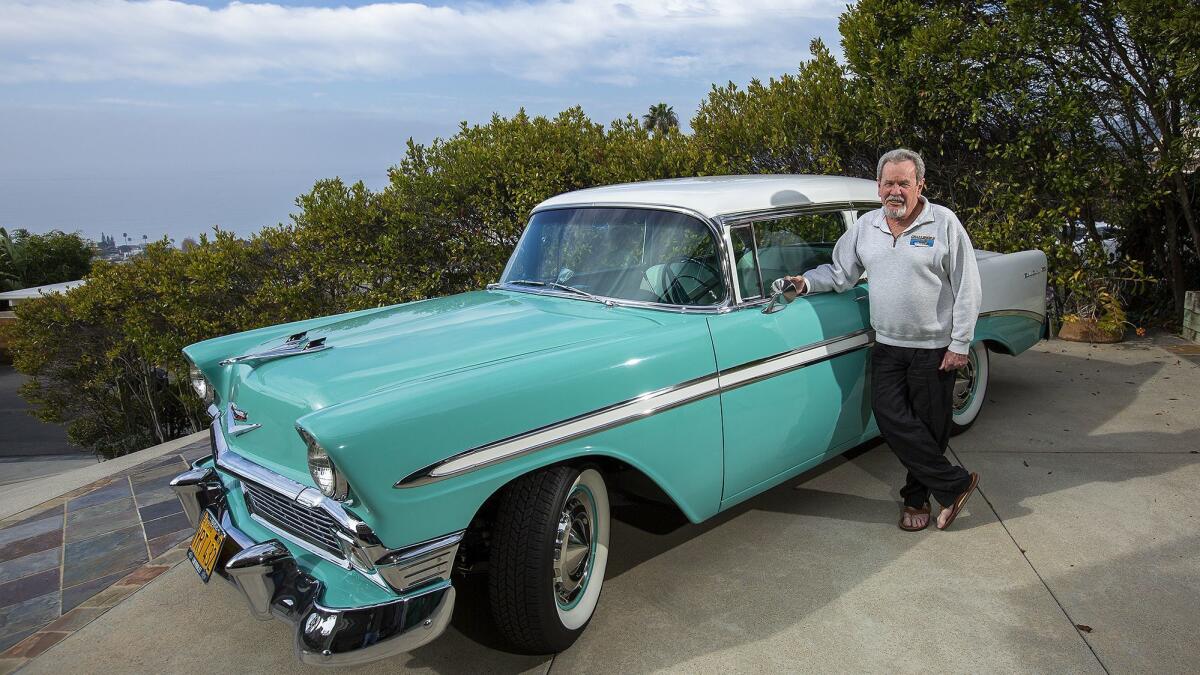

Since leaving the council in December, Boyd, 75, is fulfilling what he intended with his retirement. He splits his time between Laguna Beach and Palm Springs, where he and his wife, Michelle, own a second home. He watches antique car shows and fawns over his 1956 Chevrolet Bel Air. He plays and watches golf. And he still regularly talks to former constituents and colleagues.

“Whether you realize it or not, Kelly, you’re a Laguna Beach icon,” Rob Zur Schmiede, a former City Councilman, said at Boyd’s last meeting.

Boyd’s roots in Laguna Beach can be traced to 1871, when his family homesteaded in Aliso Canyon. Growing up in Laguna, he collected friends and followers from all corners of town — whether surfing at Thalia Street Beach as a teenager or pulling up a bar stool at the Marine Room Tavern, which he owned with his brother, Bo, before selling it in 2012.

Boyd managed to charm even those who disagreed with him, said longtime resident and former Councilwoman Ann Christoph. Though Boyd and Christoph sometimes battled over policies about trees and historic preservation, she appreciated that he welcomed her input.

“People really like him. Even if they get yelled at, they still like him anyway,” she said. “There’s something about his character, his demeanor that makes him a popular figure.”

Boyd worked to establish the Alternative Sleeping Location as the city’s first municipal shelter for homeless people. He helped reshape a view preservation and restoration ordinance while battling cancer. And after about 40 years of local discussion on the topic, Boyd helped push through the final edition of the Village Entrance project.

Now he’s ready to relax and enjoy his retirement.

“Twelve years is long enough,” he said with a laugh.

Alternative Sleeping Location

In 2006, when Boyd was elected to return to the council for the first time in 24 years, he faced a growing conversation about homelessness in Laguna Beach. The way he remembers it, people were coming into town from other cities and camping at Main Beach and Heisler Park.

“They were defecating everywhere and making a mess,” he said.

As contention among residents and the homeless population grew, the council tried various things to address the topic. It formed a homelessness task force and acted on several of its recommendations, including hiring Jason Farris as the city’s first community outreach officer and installing donation meters to collect change for homeless people.

“We said we have to do something about this,” Boyd recalled. “This is Laguna; we can’t have this.”

So when the American Civil Liberties Union slapped a lawsuit on the city in late 2008, alleging it was not doing enough to care for its homeless, city officials were stunned.

Laguna scrambled to respond and eventually reached a settlement agreeing to repeal local laws restricting people from sleeping in public areas. But residents’ complaints of people staying at popular spots such as Main Beach and Heisler Park mounted and, according to some reports, the number of homeless people increased.

The solution, as decided by the council and a consortium of local nonprofits, was the Alternative Sleeping Location, which opened on Laguna Canyon Road in June 2010. Boyd and Iseman led the charge for the new shelter, spending hours hearing from residents, talking to coalitions of nonprofit organizations and coordinating the changes.

“Even though the two had different political perspectives on many issues, they were able to work with each other and staff and community … to come up with a program,” said City Manager John Pietig.

Five years later, homelessness in Laguna Beach was the subject of another lawsuit from the ACLU, this time on behalf of five homeless people who alleged the city was not accommodating enough to people with disabilities. The city reached a settlement in the case in 2018, agreeing to start a daytime drop-in program at the ASL and reaffirming its commitment to end homelessness in Laguna Beach.

Despite the legal battles, the ASL is widely recognized as one of Boyd’s major accomplishments.

“The fact that he got that going at a time when the city was under some scrutiny was really good,” said Councilwoman Sue Kempf, who was elected last year. “The ASL was something that he was very proud of.”

View preservation and restoration

As Boyd relaxed on his couch in front of an antique car show on TV, his eyes roamed the landscape below his front porch. He said he appreciates the sweeping view, from Long Beach to Catalina Island. But he notices one spot in particular.

“See those trees over there?” he said, pointing to a grove of palms rising above the layered Laguna neighborhoods and blocking part of the ocean view.

Some community members have complained of trees, shrubs and other vegetation blocking views; others defend them as intrinsic to Laguna’s unique character.

The Planning Commission and City Council debated the issue for years. A view ordinance adopted in 2003 didn’t retroactively address view issues, and the claims process for disgruntled homeowners was voluntary and not enforced, critics said.

In 2013, Boyd called for the formation of a View Equity Committee, describing the need for it with a memory from childhood.

“I know that when my grandfather developed part of Temple Hills and all of Mystic Hills, his objective in putting those lots in was for people to enjoy those views of the ocean,” Boyd, who was then Laguna’s mayor, said at a council meeting in January 2013. “He didn’t have trees up there, believe me. I got to get paid 25 cents an hour to plant moss.”

Less than a month later, Boyd announced he had just been diagnosed with Stage 2 bone cancer.

But he said he had “no intention of stepping down.” The council chamber erupted in applause.

For the next several months, Boyd shuttled among doctors for chemotherapy, bone-strengthening injections and blood tests. He went bald. He lost more than 40 pounds. He underwent a stem cell transplant.

And he missed only one or two council meetings.

“He was so frail that he would be shaking when he was trying to stand up or sit down and would be hanging, clutching the dais to help support himself,” recalled Elizabeth Pearson, a council member at the time. “He made a commitment and he was going to do everything he could to fulfill his commitment. He went above and beyond the call of duty.”

True to his promise to “be a part of every one” of the council’s 2013 priorities, Boyd set up the View Equity Committee. The group held eight public hearings, visited 11 sites with view obstructions and toured other cities with similar view preservation issues, said Kempf, whom Boyd appointed to the committee as a resident representative.

Midway through the committee’s work on an amended ordinance, Boyd made another announcement. In December 2013, he declared himself cancer-free.

Six months later, the council unanimously approved the amended view ordinance, which allowed residents to establish their views, with photo evidence, by using the date their house was purchased or the date of the original ordinance, whichever was earlier. If neighbors could not agree, they could make claims through a tiered mediation system that ultimately would end with a council decision.

Since 2015, Kempf said, only two complaints among more than 100 claims have been appealed to the City Council, with most issues resolved through earlier mediation.

Christoph, a member of the Laguna Beach Beautification Council, said the ordinance succeeded in lessening neighbor complaints, but it affected the discussion of trees in town.

“There’s a lot of threats to trees,” said Christoph, who made an unsuccessful bid to return to the council last year. “That whole discussion has made people think that trees are not a desirable thing … it’s the whole political push to get an ordinance that caused this kind of negative attitude about trees overall.”

Mayor Bob Whalen, who served with Boyd on the council for six years, called the view ordinance Boyd’s “signature.”

“That was one of his things that he really wanted to see worked on and done, and it was a controversial issue,” Whalen said. “But that’s where he had the ability to get a group to produce an ordinance and then get it through council, because people respected the fact that he had been around here so long.”

Village Entrance

Though Boyd’s career in public office was concentrated mostly in the past 12 years, he first served on the City Council from 1978 to 1982 and is one of only two people (Wayne Baglin being the other) who were on the council in the 1970s and 2000s.

Boyd remembers when talk began swirling in the ’70s and ’80s of creating an enticing entrance to Laguna Beach. Tangible designs for the Village Entrance project at Laguna Canyon Road, Broadway and Forest Avenue grew serious in the past decade. Community members poured into the council chamber to learn about the multimillion-dollar project, question its necessity and debate its design.

At one meeting to discuss the prospect of a parking structure, Boyd strode in wearing a referee shirt and carrying a whistle, Pietig recalled.

“Kelly was like that, where he could come in with a sense of humor, lighten the room and allow people to focus on the issues in a civil, pragmatic kind of way,” Pietig said.

A construction bid for the final version of the project — with no parking structure but updated parking lots, new walking trails and bike paths and extensive landscaping — went to the council last summer. Boyd was eager to approve it.

“It’s time to move it forward,” he said at the Aug. 7 meeting. “Let’s get it done and get it planted.”

Whalen said Boyd’s “straightforward, clear-headed, decisive” leadership helped the council reach decisions on issues such as the Village Entrance.

“I wish I had his magic touch on a couple of things,” said Whalen, who took over as mayor when Boyd retired in December. “I wish I had his ability to get to the finish line on some things. He did a great job on that.”

But Boyd’s succinct nature was not always well-received by residents who valued slower deliberations, said Norm Grossman, a former planning commissioner who chaired a 1995 task force on the Village Entrance project.

“I think Kelly was more of the arena of representing his constituency and just getting things done,” Grossman said. “I’m of the exact opposite opinion, that the more of these public inputs you have … in the end, the smoother the project is.”

Legacy

At Boyd’s farewell council meeting, Whalen presented him with a resolution listing more than a dozen accomplishments of Boyd’s 16 years on the council.

In addition to the view ordinance, ASL and Village Entrance, Boyd was on the council as South Coast Medical Center transitioned to Mission Hospital Laguna Beach, Heisler Park underwent renovation and the city’s maintenance campus moved to a lot on Laguna Canyon Road. He oversaw the creation of the Community & Susi Q Center and the pedestrian and bicycle paths in the Top of the World neighborhood.

Boyd, a registered Republican, said politics didn’t matter to him during his time on the council.

“To me, it’s not are you a Republican, a Democrat, an independent, a commie, a socialist. None of that matters to me,” he said. “This is the city of Laguna Beach. That’s what matters to me.”

And, he said, he won’t take personal credit for any of the projects during his tenure.

“I don’t look at things that way, as a crowning improvement,” he said. “I look at what … we’ve done as a group, as a City Council, to make improvements to the city.”

Two council newcomers, Kempf and Peter Blake, got Boyd’s endorsement during last year’s election campaign.

Blake, a first-time political candidate and longtime local art gallery owner, said he would be “honored” to carry on Boyd’s legacy on the council.

“I’m not in any way saying that I’m a Kelly Boyd — I’m far from a Kelly Boyd. But I aspire to be a Kelly Boyd,” Blake said. “He made decisions that sometimes were unpopular and went against the grain, but he felt in his heart that he made the right decision for the community.”

As for Boyd himself, he’s happy to play golf, pop over to Palm Springs for a long weekend and enjoy the view from his couch.

“I feel great about it,” Boyd said of his retirement. “Outgoing, going, gone.”

Twitter: @faithepinho

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.