Will the cancer moonshot work? Cancer experts cite need for money and data

In calling for "a new national effort to ... cure cancer" during his State of the Union speech in January and labeling it a "cancer moonshot," President Obama deliberately evoked John F. Kennedy's 1961 commitment to "achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth."

But are the two efforts comparable? President Kennedy cited NASA's need for a $5.4-billion budget aimed at a very specific goal; Obama is hoping Congress will heed his call for a $1-billion launching fund for a much more nebulous and complicated goal.

We're not lacking for ideas, we're not lacking for talent. [But] we're scaring away some of the talent.

— Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health

But cancer and biomedical research experts speaking Monday at the Milken Global Conference in Beverly Hills, some of whom will be closely involved with the program, were hopeful that it would inspire new approaches to cancer research that could yield dividends well beyond the confines of the program itself.

"Get over the moonshot metaphor," urged Greg Simon, a former Pfizer executive, aide to former Vice President Al Gore and cancer survivor who has been named executive director of the program. "President Kennedy didn't say we're going to study 'moonology'; he put a human being at the center of the program."

The human approach has been missing from cancer research for years, researchers asserted; clinical trials of promising treatments have trouble signing up patients because their designs leave patients confused about how tests of drugs that could have painful side effects will help them.

"Right now, clinical trials are 'experiments' and the participants are 'subjects," observed Kathy Hudson, deputy director for science, outreach and policy at the National Institutes of Health, the moderator at a conference panel devoted to the program. "Patients don't want to be 'subjected'" to tests. That resistance is one reason that only 3% to 4% of cancer patients are enrolled in clinical trials.

That's a loss, because the patient's viewpoint can help guide researchers and inject a sense of urgency into a research project.

But the biggest obstacles to a successful campaign against cancer are lack of money and lack of data. In recent years, the U.S. government has systematically starved its research agencies of needed funds for basic scientific research.

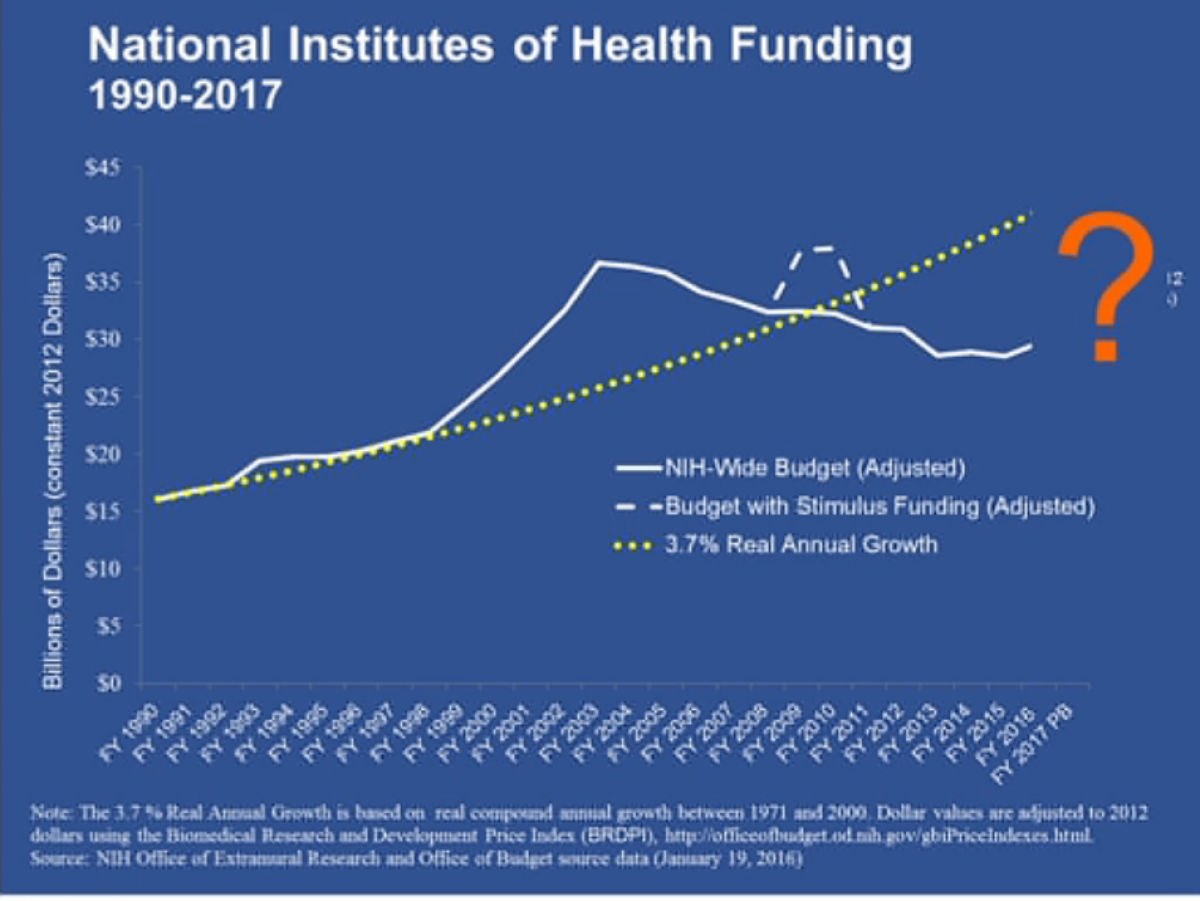

"We're not lacking for ideas, we're not lacking for talent," NIH Director Francis Collins said at a separate panel. "We're scaring away some of the talent." Young researchers today face "the lowest success rate in history" at obtaining NIH grants -- 16% of all grant applications are getting funded. NIH funding for biomedical research doubled to roughly $35 billion (in 2012 dollars) from 1998 to 2003, he noted.

"Then the budget went stagnant [and] inflation eroded our purchasing power," Collins said. The budget was sliced by $1.5 billion in mid-2013 by the sequester, "from which we have really not quite recovered. ... It's because of what's happened in the last 12 years that young scientists in particular are feeling such a squeeze."

The squeeze on funding helps drive young researchers to focus their energies on individual research that can yield publishable papers to build their credits toward tenure and grant awards, administrators say, rather than toward collaborative projects that could generate results that are more scientifically valuable.

"We're rewarding the wrong behavior," said Anna Barker, a life sciences professor at Arizona State. What's needed is more data-sharing, so that advances achieved by one project can be built on by others.

The panelists said they hope the moonshot will shift the incentives of research toward shared programs and shared data, but they acknowledged that tradition and commercial interests also have worked against that goal. Some of the most prestigious scientific journals in the world keep published papers behind expensive paywalls, not releasing them to the general public for a year or longer after initial publication.

A 2007 federal law requiring public reporting of clinical trial results to a federal database is regularly flouted by top universities and biomedical companies. A recent investigation by the medical news service Stat determined that Stanford University, for example, posted results late or not at all for 95% of 82 trials that were subject to the law. It wasn't alone.

Meanwhile, the cost of developing cancer treatments and the profits to be made from blockbuster drugs also prompts some biomedical companies to hold their research close, though that may be changing.

"We are cooperating in ways that would not have happened a decade ago," Robert Bradway, chairman and CEO of Amgen, told the audience.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.