Silicon Valley nightmare: SEC wants to crack down on screwball accounting gimmicks

Securities and Exchange Commission Chair Mary Jo White took the opportunity this week to fire a broadside at one of the most cherished traditions in Silicon Valley: companies tweaking their accounting to make their earnings look better.

The issue was "non-GAAP" financial measures -- that is, those that don't conform to generally accepted accounting principles. Non-GAAP measures are rife throughout the financial reports of tech companies, especially trying to make red ink look not so red or even magically transform it into black ink.

[CEOs] love the non-GAAP measures because they tell a 'better' story.

— SEC Chair Mary Jo White

"We've got a lot of concern in that space," White said Wednesday during a question-and-answer session at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce's annual capital markets summit. (See video below, or follow this link; her remarks start at about the 32:50 mark.)

Corporate chief executives "love the non-GAAP measures because they tell a 'better' story," White said. "It's something we're looking at as to whether we need to actually rein that in a bit, even by regulation." She asked whether using non-GAAP measures has "gone overboard." The question CEOs need to ask themselves, she said, is whether "your non-GAAP reporting and disclosures always result in a rosier picture."

White didn't specify whether the SEC is concerned chiefly with the most commonly-used non-GAAP measures or the more rococo gimmicks developed by some startups trying to persuade investors that their business models are unique, and therefore so should their accounting treatment be. Nor did she specify what action her agency might take. She did note, however, that this wasn't the first time she's warned companies about non-GAAP accounting.

Some rules already exist for non-GAAP reporting: Public companies must not give these unorthodox measures more prominence in their financial filings than conventional GAAP figures, and they must provide details about how the two categories differ.

Still, the main problem with non-GAAP reporting is that it hinders comparisons among companies -- if one is defining an apple as an orange, and another as a grapefruit, how can investors figure out which company is doing better or has better prospects? What's the most accurate picture of a company such as GoPro, the sports camera manufacturer? Is it a company that earned 25 cents per share in 2015 (GAAP), or 76 cents per share (non-GAAP)?

Companies of all sizes and in all sectors use non-GAAP measures here or there, and sometimes they do point to unusual or unique characteristics of a company or its business. But the practice is most common among youthful technology companies, where real earnings may be far in the future and highly conjectural. They feel they need a measure that indicates they're making some progress in their business, even if it can't be demonstrated in net income.

The excuse for using many such measures is thin, at best. Take the most common non-GAAP stunt, which is excluding the cost of stock-based employee compensation from a company's expenses. Companies justify this by arguing that it's a non-cash expense, so subtracting it from earnings would give a false picture of their health.

Yet this treatment of stock grants distorts the picture of a company's finances in two major ways. First, once they're exercised, they dilute the value of investors' shares; the impact is no illusion. Second, employees treat them as real pay, albeit with the potential for growth; if a company didn't issue stock to its employees, it would have to pay them with roughly the equivalent in cash. Pretending that the grants have no value and therefore don't need to be charged against income is a lie.

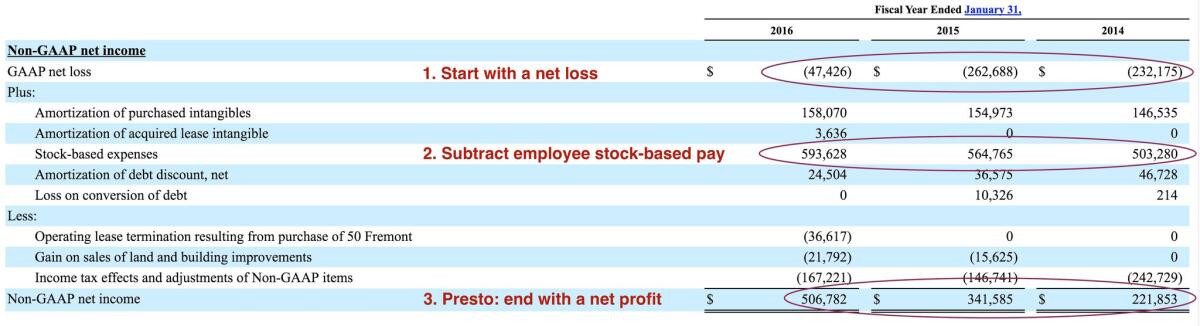

For some companies this is a huge item. At the San Francisco business-development firm Salesforce.com, for example, annual stock-based compensation equaled about 9% of revenue. Subtracting it turned GAAP losses totaling more than $542 million over the last three years into a non-GAAP profit of more than $1 billion:

Other companies have been even more creative. The coupon company Groupon, for instance, became famous for the intricacy of its non-GAAP dodges. At the time of its 2011 initial public offering, Groupon purveyed a measure it called "adjusted consolidated segmented operating income," or adjusted CSOI, which excluded such items as its costs of acquiring customers. In its IPO filing, CSOI alchemy turned a 2010 loss of 420.3 million into an "adjusted" profit of $60.6 million. Yet the acquisition of customers was the whole ballgame for Groupon: What justification could there be for treating its cost as nonexistent?

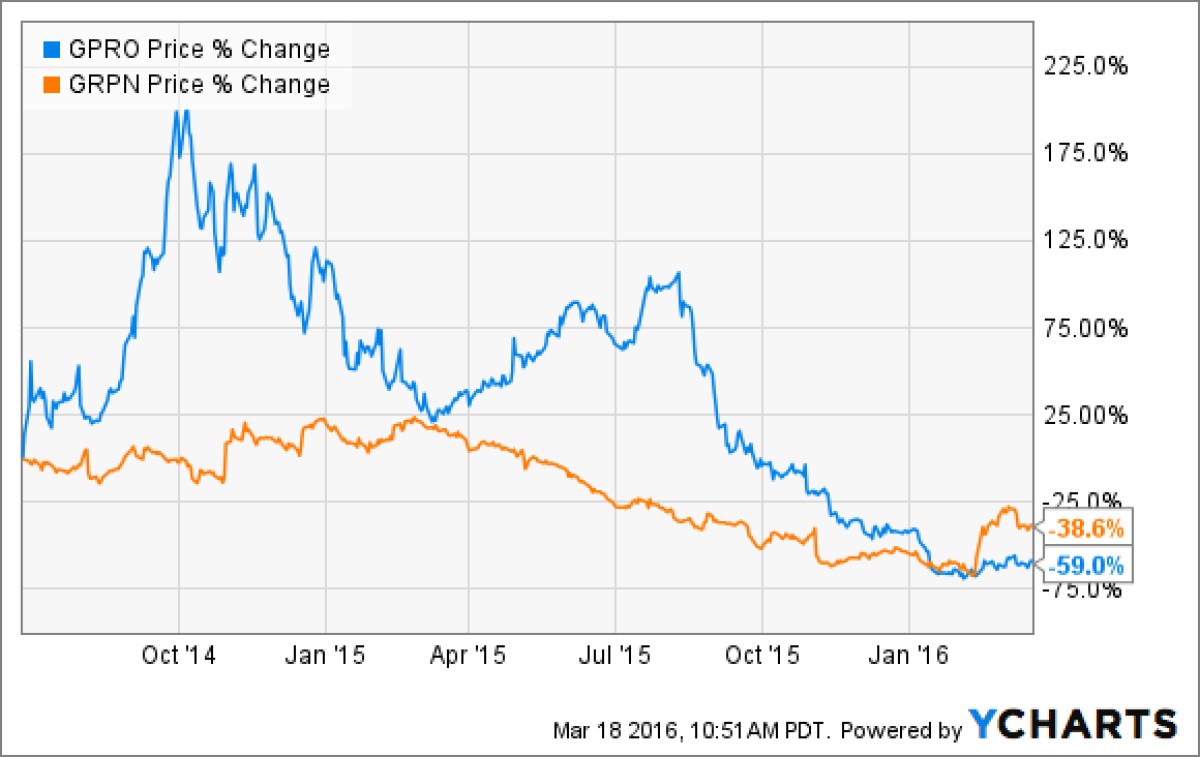

Promoters of non-GAAP trickery argue that securities analysts and attentive investors know how to back the adjusted numbers out and use them carefully, rather than treating them as real. There's some justification for this view, since it's hard for a weak company to fool the markets indefinitely by using non-GAAP accounting. Shares of both GoPro and Groupon have been on a slide over the last two years despite efforts to beautify discouraging income statements, as the accompanying graph shows.

But then what's the point of using non-GAAP accounting at all, if informed investors see through it? The answer at many companies is that these measures snare the unwary or provide promoters with the opportunity to gussy up a stock's story by arguing that the stock, or the time, is unique. Today's non-GAAP measures are merely the offspring of the metrics employed in the late 1990s to persuade investors that dot-com companies were great investments, despite showing little or no profits. Who needed profits, the argument went, when we have "eyeballs," which amounted to people flocking to online websites to gawk? The hope was that people wouldn't notice that turning eyeballs into sales was the hard part, and not necessarily in the skill set of the young thrusters claiming that their sites would change the world. That argument ended in tears, measured in bucketfuls of losses for credulous investors.

Without regulation, some companies will contrive ever more elaborate non-GAAP measures that do little but mislead. White's SEC is right to put a leash on non-GAAP accounting, and the sooner the better.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.