Column: Congress votes to expand drug testing for the jobless, an enormous waste of money

In their seemingly endless quest to ferret out the “undeserving poor” and further impoverish the needy, Republicans in Congress last week sent a bill to President Trump vastly expanding the number of unemployment applicants who can be drug-tested before receiving benefits. He’s expected to sign it.

Here are a couple of salient points about this: First, it may well be unconstitutional. Second, even if it’s not, it’s an enormous waste of money. Several states have tried drug-screening applicants for public assistance programs, aiming to deny benefits to those who fail. Universally, these efforts fail to uncover more than a tiny handful of drug users, typically below the percentage of users in the general population, and often cost more than they save.

The measure approved by the Senate on March 14 on a party-line vote, after approval by the House in February, aims to overturn a regulation by President Obama’s Labor Department that limited the conditions under which states could drug-test applicants for unemployment benefits.

Citizens do not abandon all hope of privacy by applying for government assistance.

— U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals

The idea of drug-testing unemployment applicants gained momentum during the last recession, when some states began to see it as a tool for reducing the soaring cost of unemployment benefits. “Their hypothesis (without any facts or data to back it up) was that claims would somehow substantially decrease, either as workers tested positive for drugs or declined to apply because of their drug use,” according to a survey by the National Employment Law Project.

They were blocked by the Social Security Act, which governs federal unemployment programs and forbids states to add legal obstacles to collecting benefits, unless they’re closely related to the cause of a worker’s unemployment. In 2012, the Obama administration struck a compromise deal that allowed states to test unemployment applicants in two situations — applicants who had lost their jobs for a drug-related cause, and those looking for work in fields that already tended to test workers. It was left up to the Labor Department to define those fields, and it did so in 2016. The list included occupations that require carrying a firearm, commercial drivers, aviation flight crews and air traffic controllers, railroad operating crews, and a few others under the jurisdiction of federal or state safety agencies.

Republicans immediately started complaining that the list was too narrow. Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas), called the regulation “yet another example of the blatant executive overreach that characterized the Obama administration.” His discontent, and others’, led to the measure sent to Trump.

Three problems exist with giving states nearly unlimited authority to drug-test unemployment claimants, as the GOP wishes. One is that such programs already have been ruled unconstitutional. For example, federal courts blocked Florida’s attempt to drug-test all applicants for Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, or TANF, in 2013 and again in 2014.

The courts ruled that the state hadn’t produced a smidgen of evidence that drug use was especially prevalent among TANF applicants — indeed, in one study the state had discovered that drug use among the TANF population was lower than among Floridians in general. That rendered the drug-testing an unconstitutional warrantless search, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals found. “Citizens do not abandon all hope of privacy by applying for government assistance,” it declared.

Among states that have managed to evade judicial roadblocks, the record shows that testing yields low numbers of drug users, typically well below the 9.4% assumed prevalence of drug use in the general population, often at great expense. That’s the second problem.

Utah, which started screening TANF applicants in 2012, turned up 29 positive drug tests despite screening 9,552 applicants, at a cost of $64,566. Tennessee screened more than 39,000 welfare applicants and generated 69 positive tests. An additional 116 applicants were denied benefits after they refused to submit to the initial screening. The program cost the state $23,592 in a year. Arizona screened 87,000 welfare recipients over three years, and generated a single positive test. North Carolina screened 7,600 welfare applicants in the second half of 2015, yielding 21 positive tests — a positive rate of less than three 10ths of 1%.

In fiscal 2015, Missouri spent more than $336,000 to screen 31,336 welfare applicants for drug use, sent 293 on for further testing, and generated 38 positive tests. Michigan, which started a pilot program to randomly test welfare recipients for drugs in 1999, yielded 21 positives out of 268 tests before a court halted the program. All but three were for marijuana. A new program was started in 2014 under stricter rules; 303 applicants had been tested in three counties by mid-2016, but not a single one had tested positive.

The third problem, which is most often overlooked, is that the urine tests used to identify drug users are known by medical professionals to be wildly inaccurate. As a team from the University of Oklahoma reported in 2010, “False-positive results for methadone, opioids, phencyclidine, barbiturates, cannabinoids, and benzodiazepines were...reported in patients taking commonly used medications.”

False-positives were most frequently reported for amphetamine and methamphetamine, among users of legal drugs such as Prozac, Sudafed, Zantac, and non-prescription nasal inhalers. Ibuprofen (sold under such brand names as Advil and Motrin) can generate false positives for marijuana, PCP, barbiturates, or cocaine. Naproxen (Aleve and Midol) can masquerade as marijuana, barbiturates, and cocaine. In a clinical setting, positive urine tests are often followed by more rigorous confirmation testing; in the hysterical atmosphere of a witch-hunt for drug abusers among applicants for welfare, unemployment, or other assistance, a single faulty urine test can reduce a family to absolute poverty, with no help in sight.

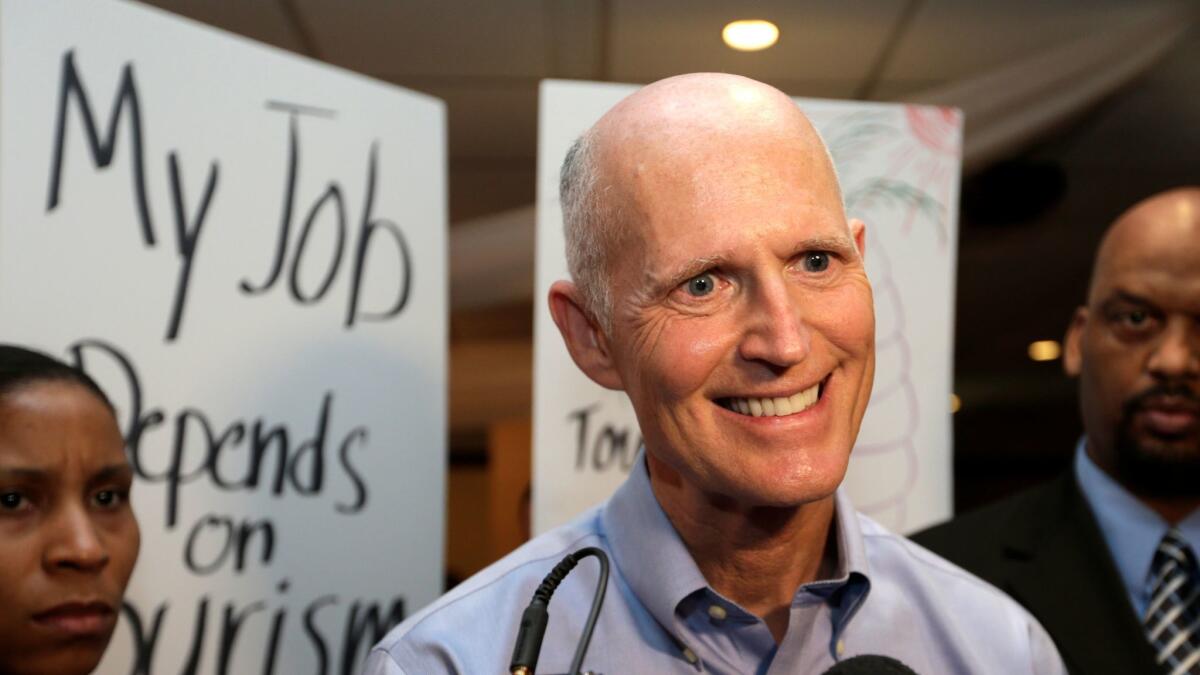

These factors underscore the real goal of such programs, which is to demonize the needy. The idea of subjecting applicants for public assistance to harsh oversight regimes is a perennial crowd-pleaser among conservative audiences, so it’s not unusual to hear conservative candidates talking as though their goal is just to weed out freeloaders from the public rolls. Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, a one-time Republican candidate for president, has called even for drug-testing applicants for food stamps, which is currently impermissible under federal rules.

Despite the consistently underwhelming results, drug testing of applicants for public assistance remains one of the most popular planks in the Republican legislative platform. This reflects a conservative mindset that equates poverty with moral turpitude — what better indicator of low morals could there be than drug use? — and that treats poverty as a crime. Demanding drug testing as a condition of unemployment assistance is merely an extreme version of this mindset, though perhaps not the most extreme.

But it takes an addled mind to continue looking for evidence of drug abuse among the needy despite repeated proof that the connection doesn’t exist. Perhaps the applicants for unemployment insurance, food stamps and welfare aren’t the ones needing to be tested for evidence of drug use.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.