Do people really overuse healthcare when it’s free?

Call it the “skin-in-the-game” argument: the notion that people will use medical care more sparingly -- and presumably more prudently -- if they have to pay a larger share of the costs out of their own pockets.

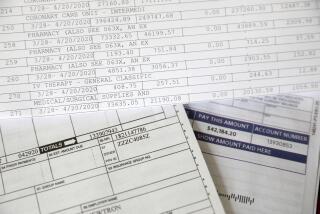

This is the idea behind health insurance deductibles and co-pays. It’s the bedrock concept of the “consumer-driven healthcare” model, which has been smiled on by conservatives in Congress who cited it in the creation of health savings accounts. The way it’s supposed to work is that by combining these tax-advantaged accounts with high-deductible “catastrophic” health plans, you’ve given people a powerful incentive to shop around for the most economically efficient healthcare they can find. Presto! You’ve put a real dent in America’s healthcare spending.

Here’s how the idea was winnowed down to its essence recently by Steven D. Levitt, the economist half of the duo responsible for that popular economics success “Freakonomics”:

“It doesn’t take a whole lot of smarts or a whole lot of blind faith in markets to recognize that when you don’t charge people for things (including health care), they will consume too much of it.”

Levitt’s complacent confidence in this idea as it applies to health and medicine prompts us to inquire: Is he right? The answer, according to numerous studies and plenty of empirical evidence, is “No.”

Levitt made his observation in the course of a debate he waged with economics blogger Noah Smith. We discussed that debate here, but Levitt’s remark came later.

Let’s start with the raw numbers. There’s no evidence that countries that provide free or low-cost healthcare to their citizens, even those who provided it to all their citizens, end up spending more. Quite the contrary.

The country with the highest per-capital spending on healthcare, by an enormous margin, is the United States, where most people have to pay for at least some of it out of pocket and many have to pay for all of it or go without. In 2010, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, the U.S. spent $7,910 on healthcare per capita, well beyond the spending of countries providing government-funded universal care such as Britain ($3,253), France ($3,835), and Canada ($4,285).

It does appear to be true that families in consumer-directed plans do cut back on healthcare services, at least at first. The question, however, is which services they reduce, and whether their choices are wise. A 2012 study by the Rand Corp. put this question at the forefront. It found that families on high-deductible plans cut spending in part by skipping such important preventive treatments as “childhood vaccinations...mammography, cervical cancer screening, and colorectal cancer screening” as well as “blood tests for glucose and cholesterol for diabetics.”

If patients “skimp on highly valuable services that can prevent more costly problems later, the savings may be short-lived,” Rand concluded.

Similar findings come from studies compiled by Aaron Carroll, professor of pediatrics at Indiana University. One examined asthma treatment among low-income families, and showed that “families with higher levels of cost-sharing were significantly more likely to delay or avoid going to the office or emergency room for their child’s asthma,” Carroll reports. “They were more likely to avoid care.”

Another study found that even modest increases in co-pay and other cost-sharing among Medicare patients saw increases in the number and length of hospitalizations, especially among patients with chronic conditions. The reason was obvious: These patients deferred or skipped tests and treatments to save money, resulting ultimately in more severe episodes of their illnesses. Carroll’s conclusion: “Cost-sharing is bad for those who need care the most.”

As he points out, skin-in-the-game systems don’t have to be blunt instruments; in some countries where they’re the rule, patients with chronic or severe conditions are exempted. But you rarely hear that option being explored by consumer-directed healthcare advocates in the U.S.

What’s most dismaying about simple-mindedly applying market economics to healthcare -- as Levitt has done -- is the failure to recognize the complexity of healthcare. The fact is that drivers of significant cost in the system are those that are least susceptible to the dollars-and-cents family budgeting that might respond to skin-in-the-game rules. It’s one thing to skip a visit to the doctor for a mild ankle sprain -- that’s not the sort of thing that adds much to U.S. spending, even in the aggregate.

But there’s little evidence that decisions on cardiac or cancer care are affected by cost-sharing -- or if it is, whether it leads to the right decisions in the long term. As a British reader of Noah Smith’s blog commented: “I have never woken up and thought: ‘It’s free, let’s have some chemotherapy.’”

The allure of market economics of the “Freakonomics” variety is based on the assumption that humans are market-responsive animals in every aspect of their lives. That’s an inviting thought, to economists and perhaps to politicians hoping to rationalize very dangerous decisions. But it’s not reality.

Faith in the idea has even led some states to propose adding premiums and co-pays to Medicaid, though the federal government has been very cautious in allowing them to do so. But even a small co-pay may be insupportable for a family living at the poverty line.

It may make conservative pols feel better that they seem to have saved the taxpayers a few bucks now, but these shallow policies may turn out to bite them where it hurts later on, and lead to injuries and deaths in the meantime. Market forces can be pitiless, and perilous.