Healthcare Bill Seeks to Preempt State Laws

“States’ rights” is one of those political shibboleths that conservatives love to trot out to block federal initiatives they don’t care for. But they’re happy to lock it away when it proves inconvenient to something they love. Like, say, the health insurance lobby.

That’s when we get something like the Health Insurance Marketplace Modernization and Affordability Act of 2005, sponsored by Wyoming Republican Sen. Michael B. Enzi and waved through committee on a party-line vote last month. I don’t know about you, but every time I see a bill carrying a “what’s-not-to-like” title like this one, I check for my wallet and I count the silverware. Then I read the thing.

Sure enough, Enzi’s bill would “modernize” the health insurance marketplace right into the Stone Age.

The measure’s goal is ostensibly to allow small businesses to jointly purchase health insurance for employees. A laudable goal, certainly. In our national system of employer-provided health insurance, the small enterprise is notoriously a weak link.

But Enzi’s bill uses small businesses and their workers as human shields to mask an all-out assault on state regulation of health insurance across the country. He proposes to preempt state regulators on a wide range of issues, replacing their standards with federal rules that in some respects have already proven to be dismal failures, and in other respects will be easily manipulated by the insurance industry. The preemptions will apply not only to small-employer plans, but to individual health insurance and large-group plans, too -- in other words, pretty much everybody.

Federal preemption has a long and checkered history, but of late it has been used largely to eviscerate state regulatory authority when that gets in big business’ face. Federal authorities have squabbled with California over whether the state’s regulation of auto tailpipe emissions violates the government’s preemptive role in setting mileage standards, for instance. (The auto industry has been holding the fed’s jacket in this rumble.) The American Banking Assn. is suing to overturn a California law that limits banks’ use of your personal private information on grounds that it’s trumped by a toothless federal version. Meanwhile, Congress is poised to enact a law superseding 200 state food safety and labeling regulations. So Enzi’s end-run is nothing new.

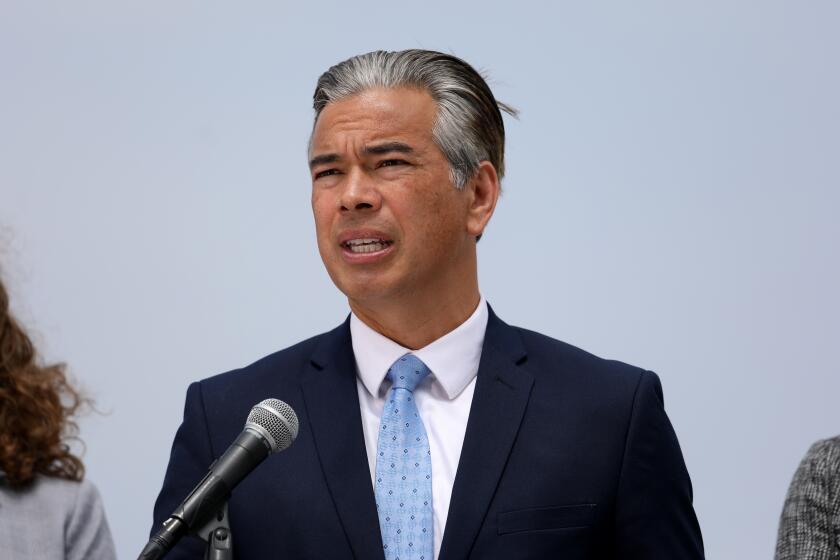

I have in my possession, courtesy of California Insurance Commissioner John Garamendi’s office, copies of 12 letters and statements delivered to the U.S. Senate by state insurance commissioners or attorneys general in opposition to the bill. Typical is Wisconsin’s, which says the bill “will have the effect of increasing rates for small businesses ... increasing the fiscal burden on state high-risk pools and Medicaid and other safety nets, and unnecessarily hamstringing effective federal and state market conduct regulation.”

Garamendi, whose department prepared an 18-page analysis of the bill, wrote that it “will do nothing to control healthcare costs. Instead it will simply shift them to older and sicker individuals.” Who will pay for those knocked out of the system by these rising costs? State and local taxpayers, that’s who. (This is what “modernization” means today.)

The bill purports to make health insurance more affordable by preempting the minimum coverage standards often imposed by state regulators, thus allowing insurers to market stripped-down policies. The downside of the provision is that insurers will try to market policies that don’t cover the very procedures that people need.

As Nevada Insurance Commissioner Alice Molasky-Arman noted, the bill would only require coverage of procedures that are mandated in 45 states. That’s a high bar. Among the current California mandates that wouldn’t qualify under the Enzi bill are mental health services; diabetic equipment and supplies; contraceptives; well-baby care; and mammographies, Pap smears, and prostate cancer tests.

The bill vastly expands the number of employee characteristics an insurer can use in setting premiums. In California, that number is three: age, family composition and geographic region. The range of prices the insurer can charge within each category, furthermore, is tightly constrained.

Under the Senate bill, insurers could also set rates based on factors such as gender and the nature of the employer’s business. The price ranges would be vastly expanded, too. Plainly, this would constitute an open invitation to the scourge known as “cherry-picking”: Insurers would have the ability to price employers with a high-risk profile entirely out of the market -- such as those employing chiefly women, or older persons, or engaged in riskier trades.

New Hampshire regulators calculate that the range of prices permitted under the bill for the same health plan would be 25.4 to 1. In other words, if the lowest-rated group paid $100 a month for its plan, the highest-rated group could be charged $2,540. This would defeat the purpose of insurance, which is designed to spread risk over the largest possible group. Instead it would allow insurers to provide coverage only to the most appealing customers -- those who don’t need it.

The provision that most unnerves state regulators is what’s known as “regulatory harmonization.” This is an attempt to reduce all health plan regulation to the lowest common denominator nationwide. States would be barred from setting their own standards for prompt claims payments, complaint response, marketing materials, capital soundness and recordkeeping.

Instead, these standards would be promulgated by a 17-member commission appointed by the secretary of Health and Human Services. Of these members, as many as 11 could represent employers, health insurers, or others in the health trades. Only two would represent consumer organizations, and only four -- two Democrats and two Republicans -- would be elected officials. There’s no provision for subjecting these standards to public hearings or public review.

“What’s galling about this is that states have been really good laboratories to learn how to do these things,” Deputy California Insurance Commissioner Nettie Hoge told me this week. “This bill sets all that aside.”

After all, the federal government has been an endless fount of good ideas for solving the American healthcare crisis, hasn’t it? Now, if only the states would get out of the way ...

You can reach Michael Hiltzik at golden.state@latimes.com and view his weblog at

latimes.com/goldenstateblog.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.