Proposed cap on federal tax deductions would hit California hard

You may be unaware of the local ramifications of one of the proposals currently at play in the danse macabre that passes for fiscal negotiations in Washington.

This is the plan to cap federal tax deductions at either a set figure or a percentage of income. Either way, it would strike deepest and hardest mostly at residents of California, as well as other populous states with high levels of government services, high state and local taxes, and relatively expensive housing.

The mortgage interest and state and local tax deductions are among the most important tax breaks that would be capped under this sort of proposal. They’re linchpins of middle-class tax planning in the most heavily affected states, which also include New York, Illinois, Massachusetts and Connecticut.

These states, of course, are also of the deepest blue, politically speaking. They also tend to support the broadest range of public services, such as healthcare for the needy. That’s what’s under attack.

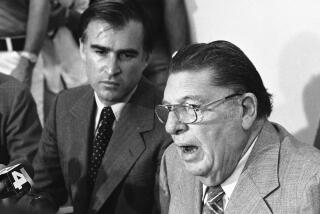

“This hasn’t gotten much attention, and it really deserves a lot of attention,” says Russell Goldsmith, chairman and chief executive of Los Angeles-based City National Bank. He points out that California’s federal tax contribution of $281 billion in 2011 was the largest of any state, but we’ve traditionally ranked near the bottom in terms of how much flows back from Washington — “we’re subsidizing the rest of the country,” he says.

“It would be unfair to penalize the states that have the highest taxes, the highest services, the highest costs and tend to be more unionized by capping deductions for local taxes and mortgage interest,” Goldsmith says. “The combination hits the residents of these biggest states much harder and much less fairly than what the president’s saying, which is to raise rates across the board.”

Goldsmith has been sounding the alarm about what a hard cap on these deductions might mean for the economies of California and the other big states. “This is a pivotal time for California’s economy,” he says, especially as the tax increases voted under Proposition 30 begin to appear. “The state’s economic recovery does not need another 2% or 3% increase in its taxes versus other states,” which could be the effect of a cap on deductions.

The virtue of the deduction cap, according to its supporters, is that it’s simple. You don’t have to tinker with marginal tax rates, you can dispense with complicated calculations to figure out what’s deductible and by how much.

Republicans and conservatives are big fans: Mitt Romney plumped for a hard cap on deductions of $17,000 to $25,000 (depending on his mood, apparently) during his presidential campaign. House Speaker John A. Boehner (R-Ohio) has offered it as a bargaining chip in the latest talks; President Obama has said he’d be open to applying a percentage dilution to deductions so that they’d deliver less of a break to higher-income taxpayers than others.

But it’s not just the rich who would be hit. Consider the mortgage interest deduction on a Southern Californiahomeworth $321,000, the median home price in November. A $300,000 mortgage on that house at 4% yields a mortgage interest deduction of almost $12,000 in the first year. For a California taxpayer with about $80,000 in taxable income, add $5,000 in state tax and $3,200 in property tax.

Congratulations! If you’re married and have two kids, you’re barely in the middle class and you’re out of deductions already. Anyone penciling out a “what-if” scenario can see that a nostrum supposedly aimed at the wealthy quickly spreads a lot of collateral damage.

The mortgage deduction is virtually the only housing program the Obama administration has. The housing industry has lagged far behind the rest of the economic recovery because federal efforts to support the housing market have been largely missing in action for four years.

Cut the mortgage deduction and you undermine an important pillar of home prices. Here, too, you hit the Obama electoral majority hard. According to figures provided by Jed Kolko, chief economist at the online real estate market Trulia, the largest mortgage interest deductions per household were claimed by nine states and the District of Columbia, which together accounted for 41% of Obama’s winning electoral vote total. California ranks second, with $5,718 per household.

One common argument raised against the deduction for state and local taxes is that it forces the rest of the country to subsidize the high-tax predilections of a few high-spending states.

Yet the list of states with the lowest per-capita state tax burden on their own citizens is eerily similar to the list of those that receive the most federal money relative to their residents’ federal tax contribution. So who’s subsidizing whom?

In 2005, the latest year for which I have both sets of figures, of the 10 states levying the least on their citizens, all but two were in the top 20 in terms of return on the federal tax dollar, and all but one (New Hampshire) were on the plus side of the books. That year Mississippi, for instance, levied the lowest tax per-capita on its residents, while collecting $2.02 from the feds on every dollar they sent to Washington. That year California’s levy on its citizens was the sixth-heaviest, per capita, but the state collected only 80 cents on the dollar from the feds.

Another virtue attributed to the deduction cap is that it allows taxpayers to choose where they want to spend their deduction credits. One problem here is that for many taxpayers, there’s no choice about some deductions — they have to pay their mortgage, and they have to pay their state and local taxes. That places the charitable deduction at risk, because it’s entirely discretionary.

One tax break that finally has landed on the table is the break on investment income, especially capital gains. In 2012, according to the tax committee, that break saved taxpayers and their heirs $130 billion; it bears repeating that this is the tax break that the wealthy are truly desperate to preserve, because it saves them so much money. For illustration, consider that in 2010, the average mortgage interest deduction claimed by taxpayers with $2 million to $5 million in income was less than $32,000. Their average tax break on long-term capital gains was about $220,000.

The return of the tax rate on long-term capital gains to its Clinton-era level of 20% from the current 15% would occur as part of the expiration of the Bush tax cuts, but even that would still mean a huge break for those who get a significant part of their income from investment returns.

Yet although Boehner is said to be amenable to allowing the rate to return to 20%, no one talks about placing a hard cap on these capital gains preferences, or requiring taxpayers to choose between the capital gains break and any of the others. The talk of taking a blowtorch to tax deductions will remain a concealed assault on the middle and working classes until and unless the preference for investment income is narrowed further or eliminated.

“People need to understand the ramifications of a simplistic solution that doesn’t add up mathematically,” Goldsmith says, “and doesn’t meet a fairness test.”

Michael Hiltzik’s column appears Sundays and Wednesdays. Reach him at mhiltzik@latimes.com, read past columns at latimes.com/hiltzik, check out facebook.com/hiltzik and follow @latimeshiltzik on Twitter.