S&P to pay $1.4 billion in claims it misled investors with rosy ratings

Ending one the most contentious cases of the post-crisis era, Standard & Poor’s Financial Services agreed to settle government allegations that it misled investors with rosy credit ratings on billions of dollars of mortgage securities during the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis.

The ratings company agreed to pay nearly $1.4 billion to the Justice Department and 19 states, including California, which has deep roots in the case and is where the litigation was filed two years ago.

S&P, a unit of McGraw Hill Financial Inc., also made a series of admissions acknowledging that it disregarded internal warnings that its ratings were too high and needed to be lowered to reflect rapidly deteriorating conditions in the housing market.

In a 16-point statement of facts, S&P admitted that executives’ fear of losing business from Wall Street clients affected decisions ranging from when to issue downgrades and whether to roll out new mathematical models intended to detect problems in the market.

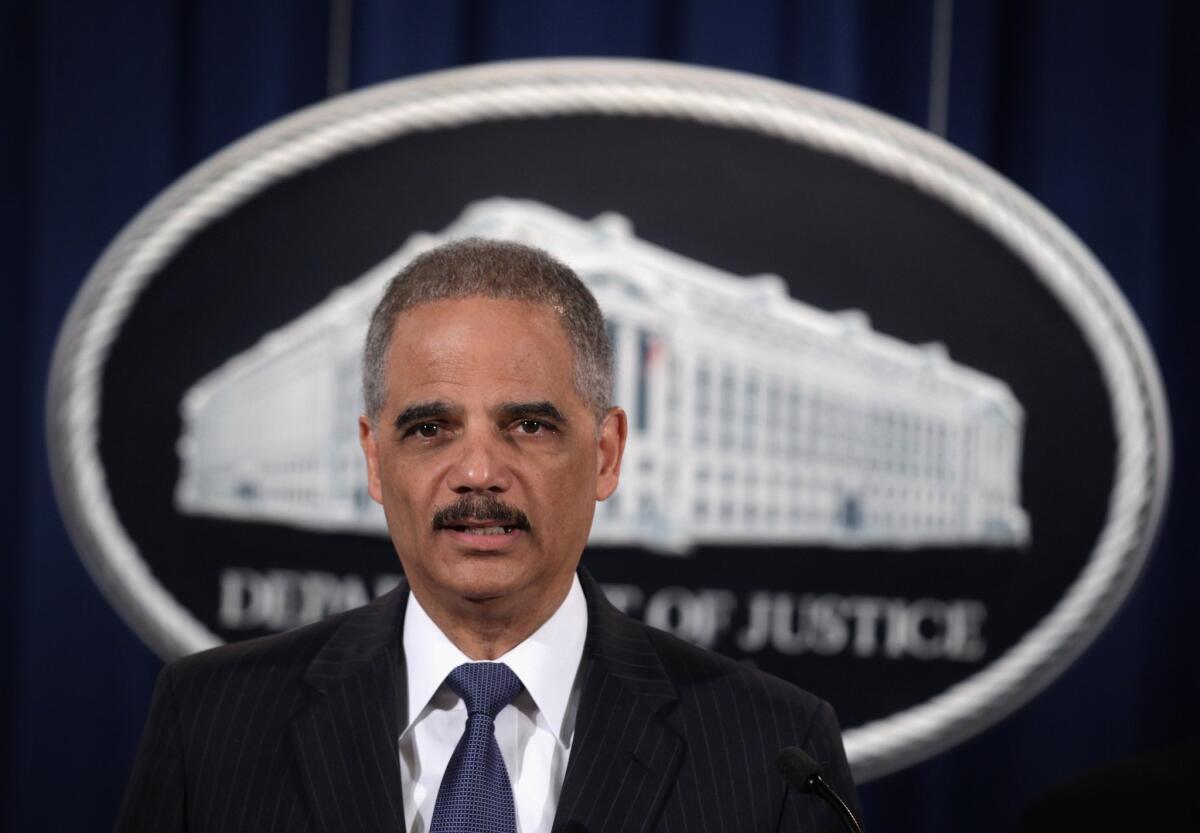

“On more than one occasion, the company’s leadership ignored senior analysts who warned that the company had given top ratings to financial products that were failing to perform as advertised,” Atty. Gen. Eric H. Holder Jr. said Tuesday.

“While this strategy may have helped S&P avoid disappointing its clients, it did major harm to the larger economy, contributing to the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression,” he said.

The announcement, which was expected, ends nearly three years of often bitter litigation that pitted the Justice Department and 19 state attorneys general against the world’s largest credit-rating company over its role in the crisis.

S&P said it settled the matter to “avoid the delay, uncertainty, inconvenience and expense of further litigation.”

Under the terms, the Justice Department will get half the settlement amount, or $687.5 million, and the states, plus the District of Columbia, will share the rest.

California will receive $210 million, and the bulk of it will go to the state’s two main public pension funds, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System and the California State Teachers’ Retirement System, to settle claims over losses they suffered mortgage securities they had bought after relying on allegedly faulty S&P ratings.

Separately, S&P agreed to pay CalPERS an additional $125 million to settle claims brought by the pension fund over allegedly defective S&P ratings on three mortgage-related securities.

“S&P profited by misleading investors who trusted its ratings,” California Atty. Gen. Kamala D. Harris said. “California’s public pension funds suffered significant losses due to S&P’s failure to honestly and accurately disclose the risk of the very investments that caused an international economic recession.”

The case, filed in U.S. District Court in Santa Ana, took more than two years of often bitter pretrial maneuvering that saw the government depose more than 100 S&P executives and other potential witnesses and to sort through more than 290 million documents, more than in any case in Justice Department history.

In what has become a peculiar footnote to the case, S&P agreed as part of the settlement to withdraw a claim that the Justice Department’s lawsuit was made in retaliation for the rating firm’s decision to downgrade U.S. debt during the mid-2011 clash over the budget between the White House and Congressional Republicans.

In the statement of facts, S&P said it reviewed “the voluminous discovery” provided by the government and acknowledged that the information gathered “does not support its allegation.”

As a measure of the bitterness the allegation provoked on the government side, Stuart Delery, an acting associate attorney general, called the S&P’s pursuit of the claim a “two-year fishing expedition,” and said the rating company was forced to acknowledge that “nothing in the mountains of information it has received from the government supports S&P’s claim of an improper motive — just as, of course, the department has said from the beginning. “

The settlement is one more turn in the long and painful process of digging out of the financial crisis of 2008, which began in the mortgage market and was compounded by the type of mortgage-backed securities rated by S&P and rival Moody’s Investor Services, a Moody’s Corp. unit, and their smaller competitor, Fitch Ratings Inc.

Federal authorities also are investigating Moody’s, said people familiar with that investigation but unauthorized to speak publicly. Moody’s declined to comment.

As the housing market heated up in the mid-2000s, Wall Street banks rushed to market hundreds of billions of dollars worth of high-yielding, mortgage-related securities, each of which required a rating on their credit quality by one of the three firms that dominated the market.

Government investigations later faulted the raters, which are paid by the Wall Street firms whose bonds they rate, for conflicts of interests and said the companies lowered their credit standards to win new business. As the housing market faltered, the securities, many of them rated AAA, crashed in value, sending global financial markets into a tailspin.

The 2011 Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission called the rating companies “essential cogs in the wheel of financial destruction.”

Already, financial institutions in the U.S. and Europe have agreed to pay more than $178 billion in total litigation costs stemming from the crisis, according to a December study by Boston Consulting Group, including high-profile settlements between government agencies and JPMorgan Chase & Co., Citigroup Inc. and Bank of America Corp.

Still, critics have faulted the government for failing to bring criminal charges stemming from the crisis against any significant Wall Street figures.

In her statement, Harris said the settlement does not “absolve S&P or its employees from any possible criminal charges.” But no criminal probe has been disclosed by anyone connected with the case.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.